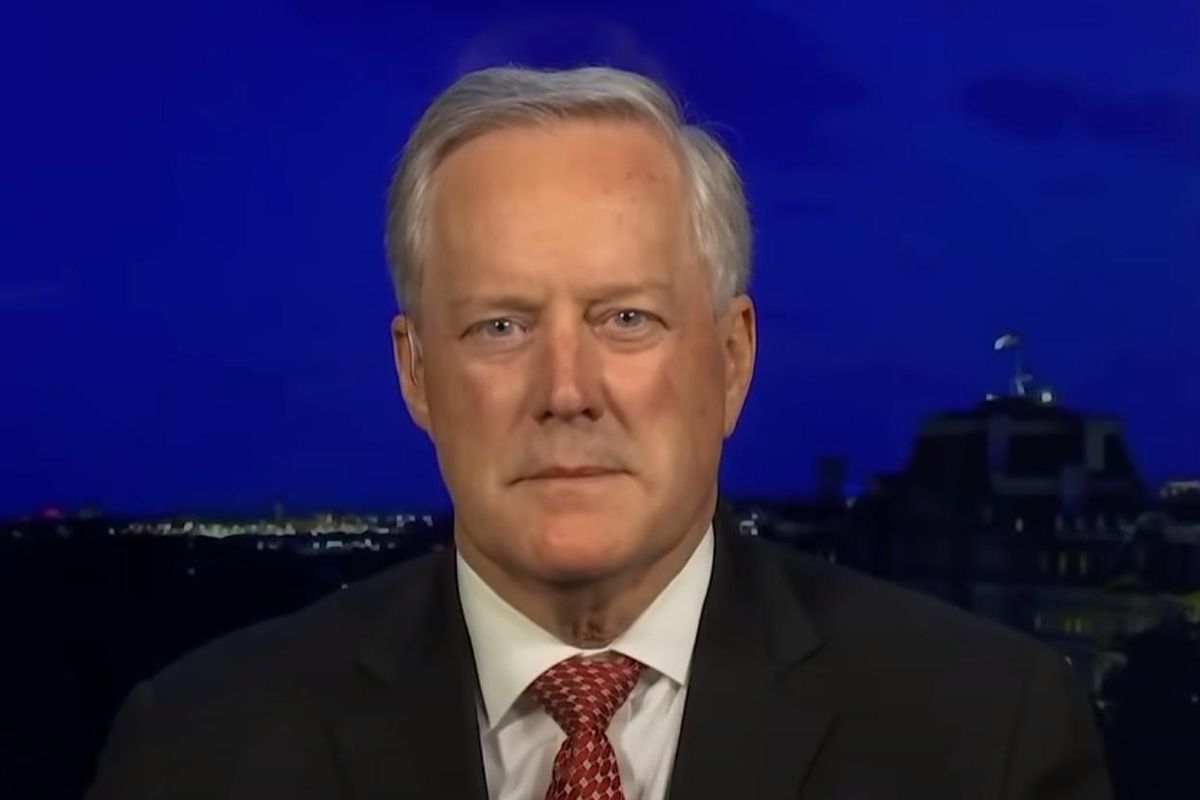

Mark Meadows, International Man Of Modesty (And Election Subverter)

Ask Reince Priebus what is the worst job in the world. If you can’t reach Reince, ask John Kelly. Either one will tell you, without reservation, the worst job in the world is being Donald Trump’s White House chief of staff. In 2017, Kelly famously stood in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery as Trump, looking down at the grave of Kelly’s son, who was killed in Afghanistan in 2010, asked him, “I don’t get it. What was in it for them?”

Don’t ask Kelly’s replacement as “acting” chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney. He’s been a political hack for so long, he can’t open his mouth without repeating the day’s Republican talking points or pushing a favorite agenda. And don’t bother asking Mark Meadows, either. Even though his legal bills are by now in the multiples of hundreds of thousands of dollars because of his involvement in Trump’s attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 election, Meadows will tell you, as modestly as he can – and that is excessively modest at this point – that the job that used to be described as the second most powerful in the United States has been reduced to just being the president’s “eyes and ears.”

Meadows on this late summer day finds himself caught between the proverbial rock of his political ambitions -- and most likely, his ability to make a living in the future -- and the hard place of Donald Trump’s copious backside, with which he is as intimately familiar as any man on the planet, having spent most of Trump’s last year in office attached thereto in a manner that is now being revealed, shorn of lies but not exaggerations, in a court of law in Atlanta, Georgia.

Meadows wants to move his state indictment for violating Georgia’s RICO statutes to federal court. His argument is that he was acting in his official capacity as a federal official – the White House chief of staff – when he worked at the direction of Donald Trump to attempt to overturn the election in Georgia. Four other defendants in the case have made the same request to move their cases to federal court: former Department of Justice official Jeffrey Clark; former Georgia Republican Party Chairman David Shafer; Republican state Senator Shawn Still, who signed on as one of Trump’s fake electors; and Cathy Latham, another Republican charged with lying to state officials by signing a fake elector certificate. It remains to be seen how the last three, who have no connection to the federal government at all, will make their arguments that their cases need to be heard in a federal court. A report in the Washington Post said that all 18 of Trump’s fellow defendants in the Georgia case are expected to make the same application to the federal court if Meadows succeeds in his motion.

Meadows spent three hours on the stand testifying on Monday, trying to make his case that everything he did in Georgia and with respect to Georgia for Donald Trump was just part of his official duties. The Post reported that Meadows did not contest the descriptions of his actions in the Georgia indictment and tried to explain away his actions as Trump’s “gatekeeper.” However, Meadows found it necessary to testify that his own keeping of the gate for the former president was quite modest when it came to how closely he was monitoring things.

Meadows testified, for example, that he was not aware of the purpose of Trump’s meeting with Pennsylvania lawmakers who he was trying to convince to hold a special session of the legislature to appoint new electors. Meadows attended the meeting, he said, only to inform three of the lawmakers that they would not be allowed in to see the president because they had tested positive for COVID. So, the “gatekeeper” told the federal judge in Georgia that he didn’t know why the people in the Oval Office were there, which would seem to make it pretty easy to get a meeting with Trump in the Oval Office. Meadows admitted attending an Oval Office meeting between Trump and legislators from Michigan but claimed that he was unaware that the Trump campaign was contesting the election results in that state. Apparently, as Trump’s eyes and ears, Meadows did not pay any attention to the former president’s constant tweeting about how the election had been “stolen” from him in every battleground state, including Pennsylvania and Michigan.

Confronted with the indictment’s charges that Meadows was involved in phone calls and meetings that had the purpose of overturning the election, Meadows said he did so because the federal government had an interest in seeing to it that the presidential election was “free and fair.” The Trump campaign, of course, lost 61 legal challenges to the elections in battleground states which they said were not free and fair, but “fixed” or “rigged.”

Meadows explained away his personal visit, along with his Secret Service detail, to the building where the Georgia recount was taking place, as a modest little side trip he took on a “personal” basis while he was in Georgia visiting his children for Christmas. He said he only knew about the Georgia recount because he read about it “in the paper,” and wanted to see it for himself because his boss was “concerned” about the Georgia election results. Meadows contended to the judge that attending a recount of ballots in an election – an inherently political event – was not associated with Trump’s political campaign. He did make the modest admission, however, that he reported his visit to Trump and to lawyers for the campaign, because, as chief of staff, he was just being modestly helpful, I guess.

You can see the problem Meadows has here. Pretty much everything Trump did between Election Day in November 2020 and January 6, 2021, when the Congress counted electoral ballots and certified the election for Joe Biden, was to overturn the election. That’s not an official duty of a president of the United States. When Trump called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and asked him to “find” 11,780 votes, it was so that the counting of ballots in the election would make him the winner by “one more vote than we have.”

Meadows had the additional burden of being, as a federal employee, subject to the Hatch Act. That act, passed in 1939, forbids political activity by federal employees while they are engaged in doing their government jobs. The act exempts the president and vice president, but does not exempt White House employees, even those working closely with the man or woman in either office. It is illegal, for example, for federal employees to make fund raising calls from the White House or the official office of the employee. An amendment to the Hatch Act in 1993 permits federal employees to be engaged in "political management or political campaigns," but only when they are off duty and not on federal property. The White House is of course federal property.

Meadows has taken the position that everything he did was part of his job as White House chief of staff. But the revision of the Hatch Act in 1993 kept the provision making it illegal for federal employees to use their authority to affect the outcome of an election. Making phone calls to arrange political meetings engaged in by the president might be legal, because it is legal for the president to hold meetings that are political in the Oval Office. But a chief of staff attending those meetings, or participating in political phone calls, such as Trump’s attempt to influence Raffensperger, would be covered by the Hatch Act.

The Supreme Court has twice upheld the constitutionality of the Hatch Act and has on multiple occasions declined to hear challenges to the act. But the Hatch Act is open to judicial review, and it may turn out that a broad reading of the act might allow some essentially political acts, such as placing a political phone call for the president, because the call by the president is allowed under the Hatch Act.

This is where the proverbial rubber will meet the proverbial road in the federal case against Trump and in the Georgia case against Trump and his 18 co-defendants: How far can you go in challenging the results of an election? Demanding recounts and filing lawsuits challenging the accuracy of vote counts and the suitability of voters and their votes are allowed. But when you lose those lawsuits, are you allowed to send slates of fake electors to the National Archives and to the Congress? Are you allowed to tell lies about electoral processes in order to overturn the results? Are you allowed to remove ballots and voting machines and their hard drives from official state election property?

When the federal court in Georgia rules on Meadows’ motion, we’re going to get the first taste of where both cases, in federal court in Washington, D.C., and in state court in Georgia, are likely to go. Evidence and the interpretation of laws will hold sway in both cases, and until that happens, all we can do is wait.

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist, and screenwriter. He has covered Watergate, the Stonewall riots, and wars in Lebanon, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels. You can subscribe to his daily columns at luciantruscott.substack.com and follow him on Twitter @LucianKTruscott and on Facebook at Lucian K. Truscott IV.

Please consider subscribing to Lucian Truscott Newsletter, from which this is reprinted with permission.

- The Strange Evolution Of Tucker Carlson’s January 6 Lies ›

- GOP Fascists Have Fired The First Shot In A New Cold Civil War ›

- No, Overturning Georgia Election Results Wasn't Part Of Meadows' Job - National Memo ›

- Juicy Columns -- Like This Gift From Meadows -- Keep Landing On My Doorstep - National Memo ›

- Nevada Attorney General Probes GOP Effort To Overturn 2020 Vote - National Memo ›