Prosecutor Robbed Lucio Of The Most Compelling Evidence To Defend Her Life

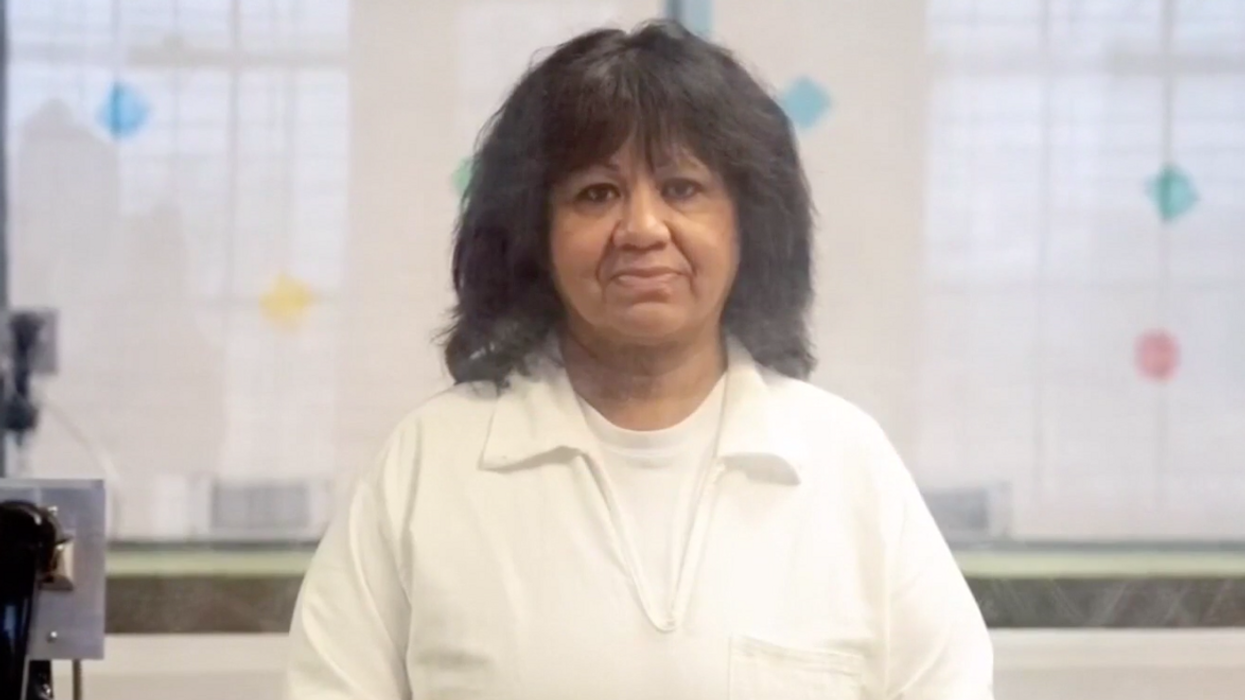

Melissa Lucio in prison

This is the seventh column in a nine-part series about Melissa Lucio and the State of Texas’ capital case against her. Read the first column here, the second here, the third here, the fourth here, the fifth here, and the sixth here, the eighth here and the final column here.

“I didn’t know she was 13, but I did it,” Ronald Skipper testified in his own defense with candor.

The State of South Carolina was trying Skipper for the rape and murder of Maryanne Wray, a 23-year-old woman he had been seen kissing before she turned up dead underneath an abandoned beach house in Garden City, South Carolina.

Skipper took the stand during the penalty phase to provide evidence that he lived an unproblematic life in correctional custody and could be trusted to serve a life sentence without posing a danger to anyone. South Carolina's 15th Circuit Solicitor Jim Dunn had asked Skipper about a prior crime, a 1978 conviction for raping a 13-year-old girl. It was one of Skipper’s three prior convictions for sexual crimes.

To offset the prior bad acts and to bolster Skipper’s testimony, his attorney, Richard Dusenbery, wanted to elicit testimony from two jail guards and a regular visitor to show the absence of problematic behavior while in prison and therefore, the appropriateness of a life sentence. Citing the reason that such evidence was irrelevant, the court disallowed these witnesses and their testimony. On June 28, 1983, a jury sentenced Skipper to death in approximately 90 minutes.

In oral argument before the country’s highest court, Skipper’s appellate counsel, David I. Bruck, warned that, without the ability to demonstrate good conduct as evidence of both character and likelihood to behave:

The Supreme Court of the United States saved Skipper’s life by relying on recently developed precedent to hold that preventing testimony about Skipper’s good conduct in jail violated his Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment rights to be free from cruel and unusual punishment and to due process, respectively.

The Court vacated Skipper’s death sentence and quoted Supreme Court precedent, insisting in the opinion of Skipper v. South Carolina: "'the sentencer . . . not be precluded from considering, as a mitigating factor, any aspect of a defendant's character or record and any of the circumstances of the offense that the defendant proffers as a basis for a sentence less than death.'" Defense attorneys can use pretty much anything that can sway a jury not to condemn a defendant. Skipper’s alive today in Perry Correctional Institution in Pelzer, South Carolina, because the Supreme Court recognized that; the state was free to pursue the death penalty again but didn’t.

The decision upholding Skipper’s constitutional rights was the first time a court recognized that the behavior after a crime was potentially mitigating evidence.

In extreme pathos, the inequities and outrages in Lucio’s situation compound themselves: a corrupt prosecutor motivated to compensate for letting a man convicted of murder to slip away; abysmal — even nonexistent — legal representation; courts that wouldn’t order a transcript of her alleged confession to be entered into the record to show that she denied abusing her daughter over 100 times to police; abuse priming her throughout her life to make her amenable to coercion; poverty so severe that she had to move 26 times between 1994 and 2007 because she couldn’t pay her utilities; a deceased child, Mariah, who died accidentally but whose passing landed her mother in jail, awaiting state-sanctioned murder.

But there’s an even deeper sadness in denying Melissa Lucio the opportunity to present evidence of her conduct in jail. Not only did false notions about her conduct appear before the jury but so did the same “blackout of information” experienced by Skipper’s jury. No one knew that Lucio managed herself quite well with guards who can be capricious and cruel and fellow inmates who can get out of control.

The absence of a disciplinary record was one of the few positives Lucio could have presented to the jury because trauma and poverty consumed so many opportunities for her. Although she had a steady job as a janitor when she was arrested, she had no significant work history to speak of. She had completed only the 11th grade. Much of the evidence that weighed in her favor proved that others had neglected, beaten, and manipulated her. That she walked the line in jail was to her credit.

Then-Cameron County District Attorney Armando Villalobos prevented her from illuminating that success. There’s a reason why a spotless discipline record appears in defense of people facing capital punishment: It’s not easily achieved, especially for female detainees who are taken to task two to three times more frequently than their male counterparts.

To be clear, it’s not only Villalobos’ fault that the jury worked with a completely false depiction of Lucio’s character. Lucio’s defense attorneys never examined her record either to see if such an argument was viable.

The larger question here is whether the pretrial disciplinary records of defendants are valuable evidence at all. The outcomes of these disciplinary systems are so specious that they hardly support any sentence, much less one of eternal slumber.

And, as Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. noted in a concurrence in the decision to reverse Skipper’s death sentence, capital defendants may behave themselves to generate some record of compliance, only to offend later. To wit, Skipper’s public record shows a number of rule violations since 2010. He unsuccessfully sued the South Carolina Department of Corrections for violating his due process rights when the department disciplined him for possession of marijuana.

Exploring the reasons why a person disobeys rules or laws is often necessary, but why someone behaves well doesn’t really deserve inquiry. It demonstrates a capacity to abide and that’s basically what prosecutors argue is absent in defendants they want to sentence to death. If lawbreaking is to be rebuked, then law abiding merits equal and opposite respect — especially if it can keep someone alive.

I can’t and I won’t impute Ronald Skipper’s propensity to break rules to Melissa Lucio. Her role in the history of violence in her life was victim, not perpetrator. Skipper may deny raping and killing Maryanne Wray, but no one doubts Wray’s assault or murder; they're real and they're crimes. Skipper's three prior sex crime convictions are not in dispute. For Lucio, the event she’s scheduled to die for wasn’t even a crime, according to many experts.

It’s not just that the Cameron County, Texas district attorneys cheated to make Lucio look bad to seduce jurors into sentencing her to death. They robbed her of a chance to make the case for her own decency, to demonstrate that what she actually did could be righteous, to say “I did it” without shame and perhaps with a hint of accomplishment.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns will now appear regularly in The National Memo.

- How The State Of Texas Fabricated Disciplinary Charges To ... ›

- Why Melissa Lucio's Jury Believed Lethal Lies That Sent Her To ... ›

- The Contrived Disciplinary Records That Sent Melissa Lucio To ... ›

- If You Want Us To Help Prove Your Innocence, Start With This Checklist - National Memo ›