By JoNel Aleccia, The Seattle Times (TNS)

SEATTLE — Carl Buher was a 14-year-old in Mount Vernon, Washington, in 2003, when the high school freshman was hit with a sudden illness: high fever, pounding headache, disorientation and purple splotches over his face and arms.

Within a day, he’d been diagnosed with bacterial meningitis, a rare and fast-moving infection, and flown by helicopter to Seattle Children’s Hospital for lifesaving antibiotics. Within weeks, he was sent to the intensive-care unit at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Within months, he had lost three fingers and both legs below the knee, amputations forced by the ravages of the disease.

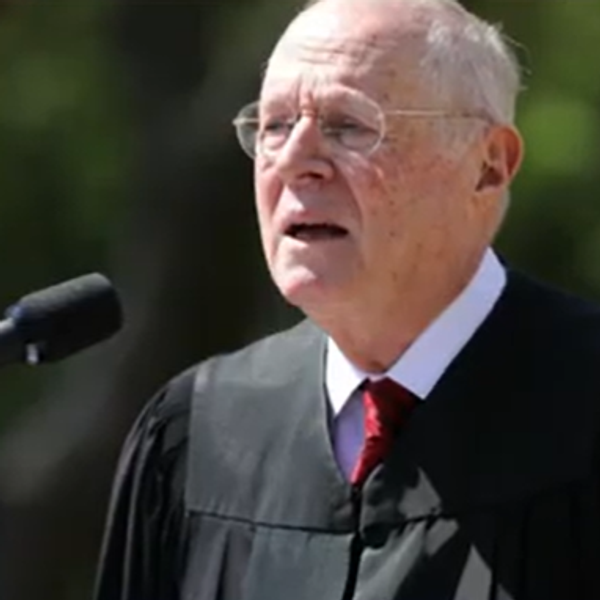

A dozen years later, Buher is a 26-year-old Seattle civil engineer who nimbly navigates despite his missing fingers and prosthetic legs. He’s also a vocal advocate for a vaccine that could have prevented his infection in the first place.

“When I got sick, none of us had ever heard of meningitis before,” said Buher, who testified last winter before a panel at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. “People don’t know there’s a vaccine and that they should be vaccinating their kids.”

On Wednesday, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which sets U.S. standards, is expected to decide whether a new vaccine to prevent meningitis strain B — the type Buher contracted — should get the nod for widespread use.

The question is whether the meningitis B vaccines used to halt recent college campus outbreaks in New Jersey, California and Oregon will be included among routinely recommended shots — as vaccines that target four other types of meningitis already are.

Bacterial meningitis is an infection that attacks the linings of the brain and spinal cord. It’s spread by close contact through respiratory secretions, such as kissing or sharing drinking glasses, which puts teens and young adults particularly at risk.

“We support the most broad-scale recommendations that the committee can do,” Buher said.

An estimated 30 to 40 infections and three to four deaths each year could be prevented if the panel were to vote for routine meningitis B vaccinations, surveillance data suggest.

But insiders say concerns about the relatively small number of young people affected by meningitis B infections — 50 to 60 cases a year — as well as questions about the lasting effectiveness of the vaccine, potential problems with delivering it and overall costs — could steer the committee toward a ruling that stops short of a wide advisory.

Instead, the group could recommend a “permissive” vaccination, said Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert and the chief of the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. That would allow doctors to deliver it and insurance companies to pay for it, but wouldn’t place it on the list of must-have shots on which parents rely.

“That’s my sense,” Offit said. The shots — which run $130 apiece and require two or three doses — would be included in the federal Vaccines for Children program, which provides vaccines at no cost to children whose families can’t afford to pay for them.

“I think the advocates would be happy that this is a very good start,” said Offit.

But to Buher and others, including the National Meningitis Association, it’s far less than they’ve been demanding.

Lynn Bozof, president of the association, lost her 20-year-old son, Evan, to meningitis in 1998. At that time, a vaccine to prevent the infection was used to protect U.S. military recruits, but wasn’t approved in the wider population.

“There was a vaccine available, and we didn’t know about it,” the Georgia mother said. “This will be the same thing: Why didn’t someone tell me? Why didn’t I know?”

Bozof said she fears that only motivated parents with well-informed doctors will understand the benefits of the vaccine — until it’s too late.

“For the average person, it is not going to be on their radar to be looking out for that vaccine,” she said.

Linda Dahlstrom Anderson, a Seattle mother whose 7-month-old son, Phoenix, died nearly a decade ago after a meningitis B infection, said such a lack of knowledge leaves an entire community at risk.

“They’re not statistics, they’re children,” said Dahlstrom Anderson, who also has an 8-year-old son she plans to protect against the disease. “Each one represents a whole universe of people. With Phoenix, it’s hundreds of people.”

The fight for wider use caps a long and contentious effort to make a meningitis B vaccine available in the U.S.

Since 2005, vaccines have been licensed in the U.S. to protect against four strains of meningitis: A, C, W-135 and Y. Since 2011, ACIP has recommended the routine use of the shots in kids ages 11 to 18, with booster doses at 16.

But until last year, no vaccine was licensed in the U.S. to prevent infections caused by strain B, the type linked to outbreaks that caused 13 infections, including a death, at Princeton University and the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2013 and 2014. This year, seven people have been sickened by meningitis B at the University of Oregon, including one student who died.

Now, however, there are two vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration that target strain B: Trumenba, made by Pfizer, and Bexsero, originally made by Novartis. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices currently recommends them for people aged 10 to 25 with underlying illness and during outbreaks — but not for the broader adolescent and young adult population.

Offit and Dr. William Schaffner, a Vanderbilt University infectious-disease expert, were both part of the CDC’s work group that studied the meningitis B vaccines.

“The work group has been remarkably studious and thorough,” Schaffner said. “They’ve looked rigorously at the morbidity and the mortality of the disease.”

The group has noted that all meningitis infections in the U.S. are at historic lows, with about 550 cases in 2013, down from a peak of about 3,800 cases in the late 1990s. Although individual illnesses and outbreaks are rare, they’re devastating to the communities — and the families — they strike.

The infections are caused by Neisseria meningitidis bacteria. When the bacteria infect the lining of the brain and spinal cord, it’s called meningitis. When the infection remains in the blood, it’s called meningococcemia. About 10 percent of people infected with the bacteria die, and an additional 20 percent are left disfigured, disabled or deaf, the CDC notes.

“For me, vaccination is not theoretical. It’s intensely personal,” Dahlstrom Anderson said. “When I think about vaccination, it comes down to that one little, sweet face.”

Neither Offit nor Schaffner could say for sure how the panel will vote, or even whether the scheduled vote was certain to occur. The group could decide to postpone a decision.

—

(c)2015 The Seattle Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: Meningitis B survivor Carl Buher battled a life-threatening infection in 2003, which resulted in the loss of three fingers and his legs below the knee. He recently testified in favor of widespread use of new vaccines to prevent the infection. (Sy Bean/Seattle Times/TNS)