By Amina Khan, Los Angeles Times

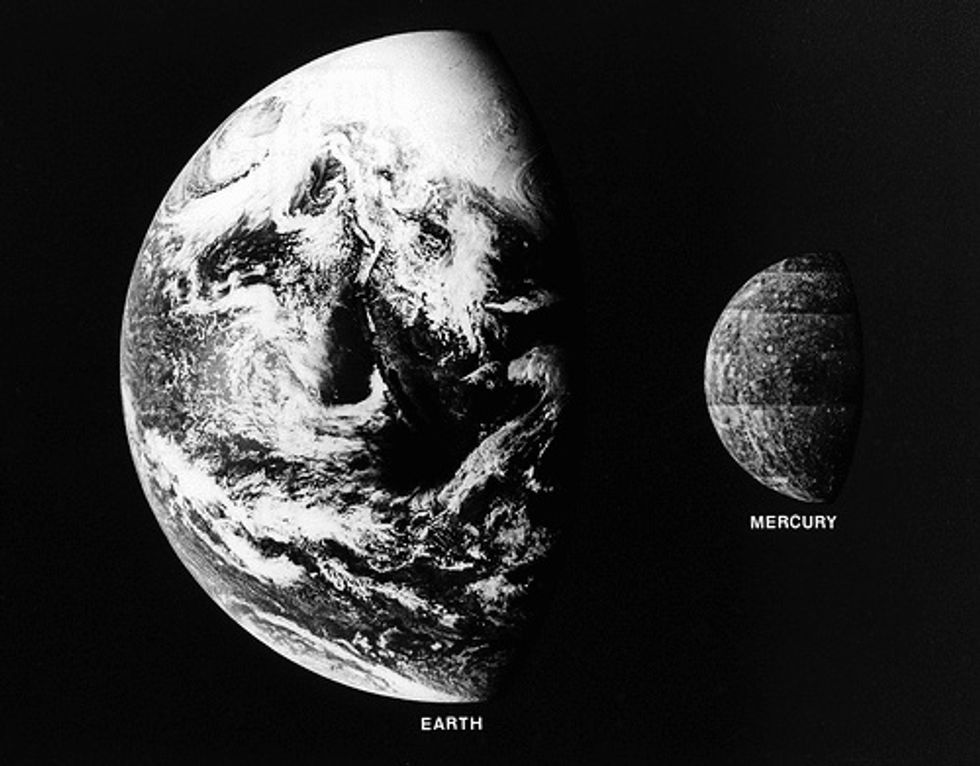

They say the world is getting smaller — and in Mercury’s case it’s literally true. Though it’s already the tiniest planet in the solar system, scientists say Mercury is still shrinking — and signs of that contraction can be clearly seen in distortions of the planet’s searing surface.

The findings, published in Nature Geoscience, solve a decades-old mystery about the evolution of the little planet’s interior and provide scientists a window into the long-term changes that affect other worlds that don’t have Earth-like plate tectonics.

“Determining the extent to which Mercury contracted is key to understanding the planet’s thermal, tectonic and volcanic history,” the study authors, led by Paul Byrne of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, wrote in the paper.

Mercury is a weird little world. As the solar system’s innermost planet, it sits less than 36 million miles from the sun — less than two-fifths of the Earth-to-sun distance. It’s mostly made up of its heavy iron core, which has about a 1,255-mile radius and leaves a thin rind of just 261 miles for its crust and mantle. Even though it’s unbearably hot, the planet also hosts permanently shadowed regions inside craters that are among the coldest spots in the solar system.

Researchers have long thought that Mercury must be shrinking, because as the planet cools, and the liquid iron core turns solid over time, it contracts. If so, signs of deformation should show up on the planet’s surface — like a plump, smooth-skinned grape that dries up, shrinks and turns into a wrinkly raisin.

Sure enough, when NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft flew by the planet in 1974 and 1975, it discovered strange, snaking “lobate scarps” on the surface of the planet. Those scarps, which are Mercury’s version of mountain ranges, were the signs that the planet had shrunk, causing its rocky skin to deform.

But Mariner 10 imaged only 45 percent of the planet, and scientists could account for only about 0.5 to 2 miles of shrinkage in the radius. The models said that Mercury’s radius should have shrunk roughly 3 to 6 miles over the last 4 billion years, since its crust solidified. Were the models wrong? Or was it simply that we hadn’t seen enough of Mercury?

NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, which flew by the planet in 2008 and 2009 and entered Mercury’s orbit in 2011, solved the mystery by mapping the remaining 55 percent of the planet that Mariner 10 missed. Scientists found that the lobate scarps covered the whole globe randomly — and that these weren’t the only signs of shrinkage. The scientists found wrinkle ridges all over Mercury’s volcanic plains, and though they’re not as high or as dramatic as those lobate scarps, they’re also a reliable sign that Mercury has been contracting, and can help researchers measure how much volume has been lost.

Based on this new view of Mercury, the researchers found that the planet’s radius had probably shrunk about 3 to 4.3 miles since its crust solidified — safely within range of the theoretical predictions.

“The findings provide a global framework for investigations into Mercury’s surface and interior evolution,” planetary scientist William McKinnon of Washington University in St. Louis wrote in a commentary on the paper.

All planets, Earth included, are cooling down over time — but the findings don’t apply to Earth because our home planet has constantly shifting tectonic plates and Mercury is a one-plate planet. Still, these wrinkly, mountain-like features have also been seen on the moon and on Mars, and Mercury could make it a model for what happens to other single-plate planets.

“Mercury provides an example of what may really happen to a planet that is shrinking,” McKinnon wrote.

Photo: Lunar and Planetary Institute via Flickr