By David L. Ulin, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

The Sick Bag Songby Nick Cave; Canongate (162 pages, boxed, $49.50)

___

Nick Cave has long operated in a particular rock ‘n’ roll tradition: that of the poete maudite. Patti Smith, Jim Morrison, Lou Reed, Bob Dylan — these are some of the analogues to Cave’s creative posture. Not surprisingly, like all of them, he has not only made music but also written books.

Cave’s first novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel, appeared 25 years ago; his second, The Death of Bunny Munro, came out in 2009. He has also published two collections of lyrics and occasional writings, and now an idiosyncratic diary of sorts, The Sick Bag Song, which traces what let’s call the inner life of the Bad Seeds 2014 North American tour.

The Sick Bag Song draws its title from the method of its composition; Cave wrote it longhand on air sickness bags while flying from city to city, Kansas City to Milwaukee to Minneapolis, and part of what it recounts is an endless sequence of hotel rooms and stages, the distance from home and family.

“I awake hanging from the ceiling in the Westin, Calgary, Southern Alberta,” he writes in one sequence. “I spider down into my clothes and fling wide the window!”

Hyperbole, yes, although that, as it turns out, is not what Cave has in mind here. Rather, he wants to evoke a certain state of statelessness, of rootlessness, of being lost in the middle of his life with nowhere, particularly, to turn.

“I carefully concoct a paste in a bowl and I paint my hair black,” he writes in one of the book’s most revealing passages. ” … In the right eye, / in the blue, is a little brown discoloration and the whites / Are beginning to yellow. There is a lover spot on my right temple / A spider-vein on my right nostril. The bathroom light is brutal. / I reposition my face so that I stop looking / Like Kim Jong-Un and start looking more like Johnny Cash.”

This is no rock star posing — although there is some of that here, names dropped: Cash, Dylan, Bryan Ferry — but a kind of brutally direct explication of aging, in a field where aging still is not part of the discourse in any fundamental sense.

In that regard, The Sick Bag Song has more in common with a certain sort of contemporary memoir, using the mundane, the everyday, as a lens through which to explicate the broader experience of living, with all its degradations and its loss.

Indeed, it’s not hard, reading these pages, to imagine the title in terms of the body itself, body as sick bag, as container of both flesh and its deconstruction, of the sickness, the decay, that awaits. This is a key aspect of Cave’s aesthetic, in both his music and his writing, an almost gleeful willingness to peel back the surfaces and expose the elemental realities underneath.

“The Sick Bag Song is the leavings,” he tells us:

The Sick Bag Song is the scrapings.

The Sick Bag Song is the shavings.

The Sick Bag Song is the last vestiges.

The Sick Bag Song is the bile and the tripe.

In the face of that, what other choice do we have but to embrace the moment-by-moment nature of our existence, even as we know it cannot last?

Cave is strongest on such moments, such perceptions, on the temporary, evanescent satisfactions of this fleeting world.

Or, as he writes from Louisville, after a tour stop:

“Later still, we file onto the bus and our tour manager counts heads and we cling to our paper coffee cups, and as the bus turns into Main Street down comes a sudden summer shower and someone puts on ‘Kentucky Rain’ by Elvis Presley and I see, through the window, for an instant, along one of the adjacent streets that leads to the Ohio River, under the Big Four Pedestrian and Bicycle Bridge, a group of representatives from the emergency services, dressed in black jackets and peaked caps, dragging something from the rain-pocked river.”

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

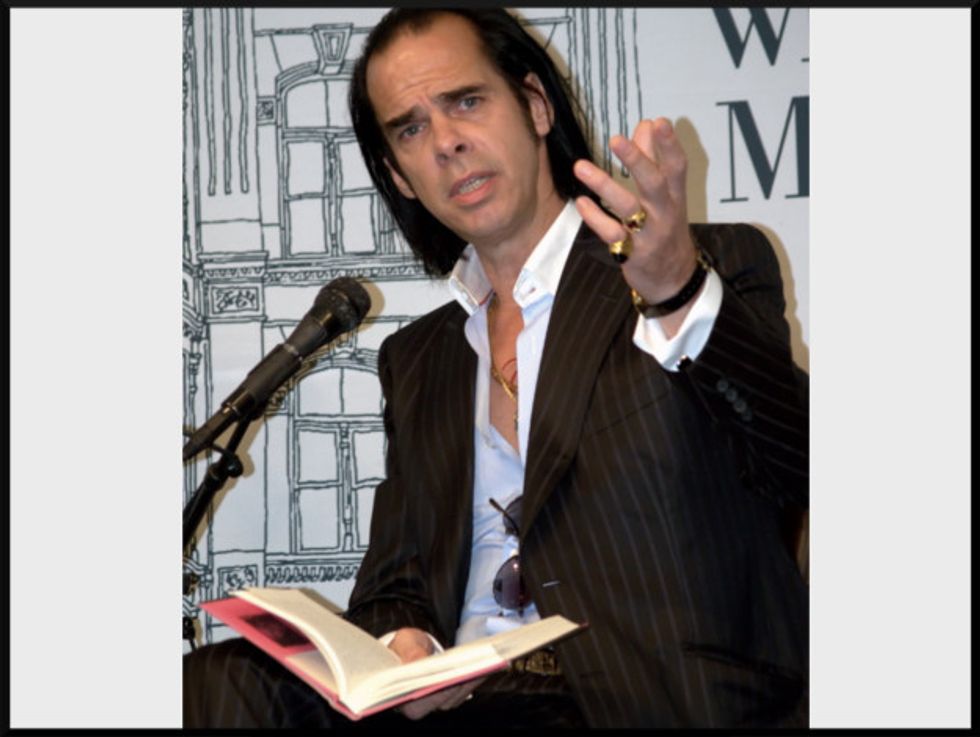

Photo: David Shankbone via Wikicommons