Ohio Primary Raises New Election Worry: Rejected Provisional Ballots

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Ohio's Democratic presidential primary winner was never in doubt, but its voting process was.

The April 28 primary, the second statewide vote-by-mail contest since the pandemic interrupted the 2020 election, highlighted new complexities facing voters if the nation shifts to mostly absentee voting this fall.

In addition to postal delivery delays possibly disqualifying hundreds of thousands of ballots—as was seen in Wisconsin's April 7 primary—Ohio's saw legally registered voters who waited until the eleventh hour to vote wrestle with the vote-by-mail process and get prevented from casting a ballot that would be counted.

"I went on Twitter and discovered that I could vote [using] a provisional ballot and demand it from them [county election officials]," said Sarah Schoeppner, a grocery worker who recounted her and her father's experience during a briefing by the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which runs the nation's largest election protection hotline. "They said that they would give it to us, but that it would probably not be counted because we didn't get the absentee ballot application in on time."

"We believe that Sarah's experience is one encountered by thousands of people across Ohio who are very confused about the deadlines that apply for absentee balloting," said Kristen Clarke, Lawyers' Committee president and executive director. "We are also very concerned about officials who may have discouraged people like Sarah from casting a provisional ballot in person today."

Ohio is the second state with mostly polling place-based voting to rapidly shift to voting by mail in response to the pandemic. (In 2018, 21 percent of Ohio's 8 million registered voters cast absentee ballots.) But unlike a special election in Maryland's seventh House district that was also held on April 28, where Maryland voters who did not receive ballots in the mail were sent PDFs online of their ballot and had more in-person voting options, Ohio's primary voters faced more restrictive rules.

Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, canceled the March 17 primary at the last minute due to the pandemic. Initially, Secretary of State Frank LaRose, also a Republican, wanted to send all voters an absentee ballot application and reschedule the vote in June. However, the GOP-majority legislature overrode those plans and imposed a regime where almost all voters had to cast an absentee ballot. There were short timetables to apply for a mail-in ballot, to receive it in the mail, and to return it with a postmark no later than April 27.

"There were a number of restrictions that were in place in Ohio that made voting incredibly difficult," Clarke said. "First, absentee applications were not automatically distributed to voters. The absentee ballot applications did not include postage-paid envelopes. There was an unnecessarily restrictive deadline imposed for the return of the absentee ballot. There were no in-person voting opportunities today [April 28] except for people with disabilities and people who were homeless."

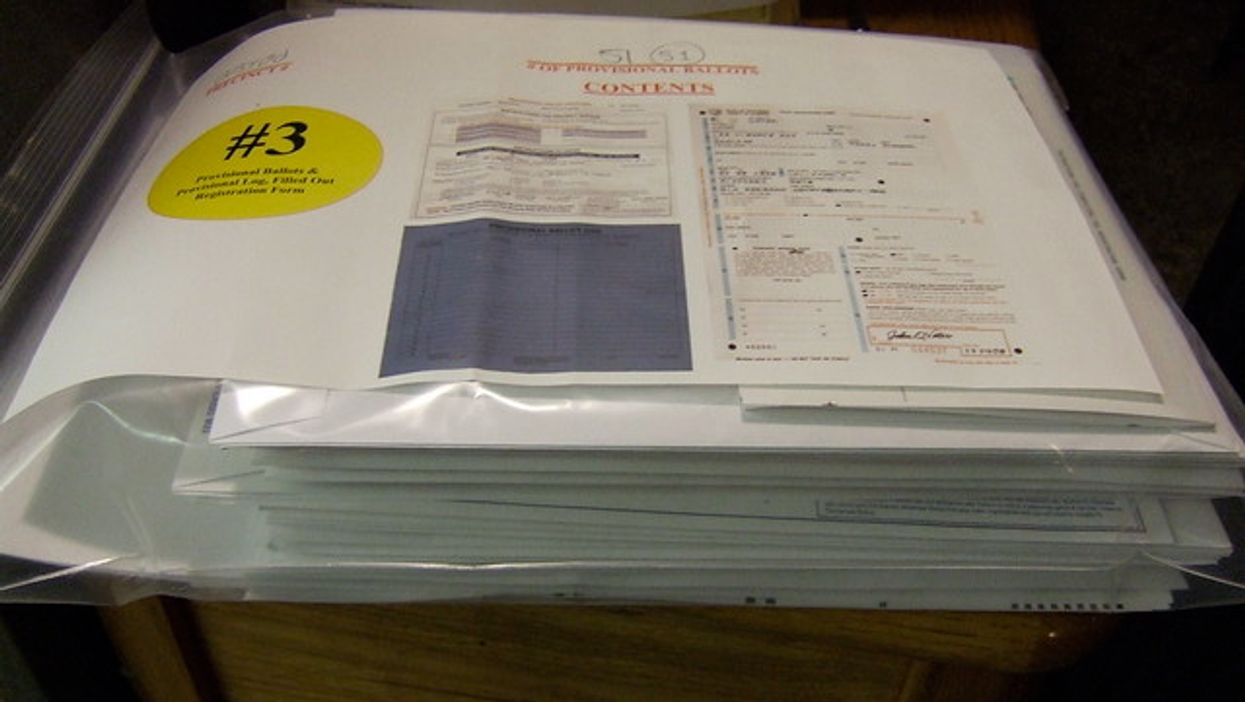

Clarke explained that voters who had applied in time for an absentee ballot, but did not receive it in the mail, were entitled to vote by a provisional ballot. That back-up option combines a voter registration form and a ballot. These voters and ballots are reviewed and authorized before being counted. Even though Ohio counties only had a single in-person voting site, there was widespread confusion over these back-up ballots.

"There was a lot of confusion around this and there were some voters who were told that if they did not request a provisional ballot [when applying for a mail-in ballot], that they shouldn't bother trying to vote today," Clarke said. "That instruction from officials may be in violation of the Help America Vote Act, which allows all voters who believe they are eligible the right to participate in a federal election. And we are looking closely at this."

To make matters worse, as the Ohio primary approached, which also had local elections on the ballot, LaRose wrote to his state's congressional delegation that the U.S. Postal Service was not delivering ballots in time. A scenario was emerging where some volume of voters, already burdened with having to apply for a second time to vote—to obtain an absentee ballot—were not poised to receive that ballot and then had to go to limited numbers of in-person voting centers if they wanted to vote.

Thus, like Wisconsin's fraught April 7 primary, where nearly 1.3 million voters requested an absentee ballot and nearly 200,000 ballots did not meet delivery deadlines and were not counted, Ohio's election officials were waiting for 517,000 of the 1.98 million ballots they sent out to be delivered as of April 27, when they had to be postmarked to count.

"We have 1.4 million ballots cast. There are still 500,000 that have not yet been reported back in," said Mike Brickner, Ohio director for AllVotingIsLocal.org, at the Lawyers' Committee briefing on primary day. "There's a lot of concern that many of those ballots may not reach voters in time, and many [voters] do not want to go to the boards of elections today because they have health concerns or other issues."

But unlike Wisconsin, which has Election Day voter registration and still had some in-person voting options (though vastly curtailed due to poll worker shortages), Ohio's all-mail primary had more restrictive rules that raise additional red flags if the pandemic's voting regime continues in the general election.

In addition to untold tens of thousands of mail-in ballots being delayed by postal delivery and possibly disqualified, thousands of provisional ballots may also be in play as Ohio's verification process unfolds after Election Day—where they are the last votes to be counted. (In 2018, nearly 101,000 Ohioans cast provisional ballots, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission reported. Only California and New York cast more.)

For Ohio's April 28 primary, mail-in ballots postmarked up to one day (April 27) before the election can arrive up to 10 days later (May 8) and still count. County election boards have one additional day (May 9) to validate provisional ballots before counting them.

Disqualifications and delays of hundreds of thousands of ballots could undermine the public's acceptance of the outcome of the fall's general election, the nation's leading scholars in election law, politics and media said in a just-issued report coordinated and produced by Richard Hasen, a University of California, Irvine, law and political science professor.

"Even before the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic arrived in the United States, close observers of American democracy worried about the public's faith and confidence in the results of the upcoming November 2020 U.S. elections," said the executive summary of "Fair Elections During a Crisis: Urgent Recommendations in Law, Media, Politics, and Tech to Advance the Legitimacy of, and the Public's Confidence in, the November 2020 U.S. Elections." "Americans can no longer take for granted that election losers will concede a closely-fought election after election authorities (or courts) have declared a winner," it continued.

The report's first legal recommendation sought to avoid what has been seen in Wisconsin and Ohio, the first two statewide vote-by-mail elections since the pandemic.

"States should adopt reforms to improve the absentee ballot and provisional ballot processes—both in terms of access and security," it said. "In particular, states should reduce… counting delays that could cause significant shifts in vote margins after in-precinct results are reported on election night."

Mass disqualifications of ballots and counting delays could accelerate disinformation where candidates claim victory based on early and incomplete results, and then seek to disrupt the counting while arguing in court that they should be declared the winners.

"Incendiary rhetoric about rigged or stolen election is on the rise, and unsubstantiated claims of rigged elections find a receptive audience especially among those who are on the losing end of the election," the scholars said. "American elections are highly decentralized, leaving pockets of weak election administration which can further undermine voter confidence in the process. The COVID-19 pandemic, which hit the United States hard beginning in March 2020, has only exacerbated concerns about the fairness and integrity of the 2020 elections."

But the first two statewide elections embracing the go-to solution for voting in a public health crisis, voting-by-mail, in Wisconsin and Ohio, show that tilting of the rules by the most partisan Republicans in swing states is not merely a concern. It is a fact.

"We believe that Ohio is an example of the way not to run a vote-by-mail system," said the Lawyers' Committee's Clarke. "It most certainly appears that Ohio is on pace to have one of the lowest turnout rates for a presidential primary election in modern times."

Steven Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He has reported for National Public Radio, Marketplace, and Christian Science Monitor Radio, as well as a wide range of progressive publications including Salon, AlterNet, the American Prospect, and many others.

Trump Cabinet Nominee Withdraws Over (Sane) January 6 Comments