The immigration policies of Donald Trump’s presidency would have no room for his GOP predecessors Ronald Reagan or George H.W. Bush—who both embraced work visas, family unification, easy border crossings and a better relationship with Mexico.

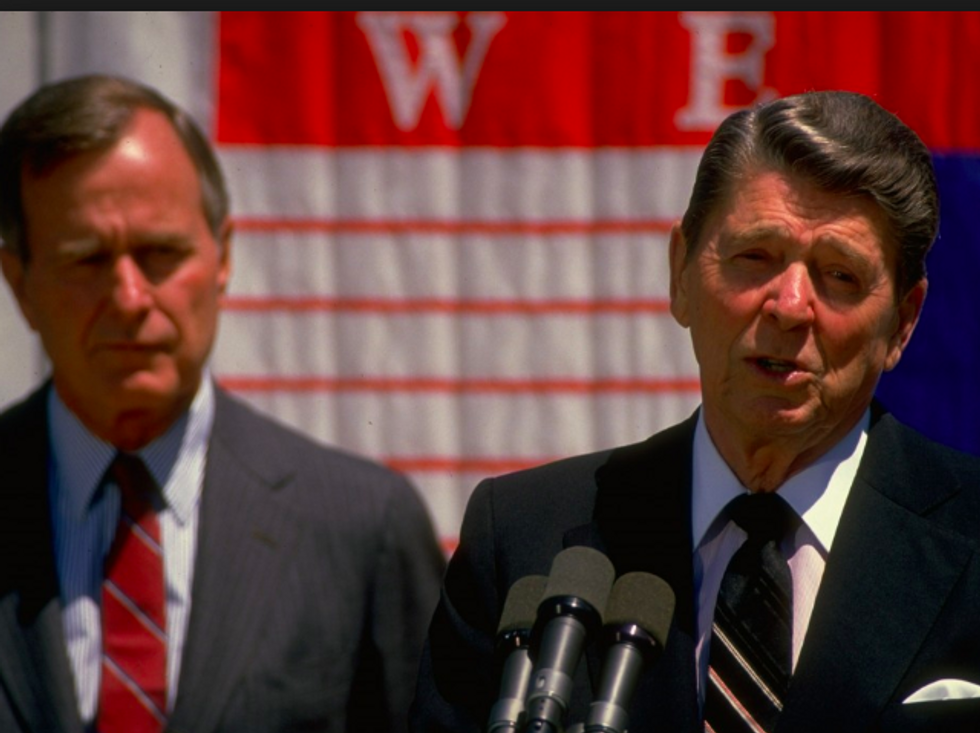

That counterpoint can be seen in a very short video clip from the 1980 presidential election where Reagan and Bush—who became Reagan’s vice president for two terms before winning the presidency in 1988—were asked about immigration at a campaign debate in Texas. Their responses show just how far to the right the Republican Party’s current leader, President Trump, and voters who have not left the GOP to become self-described political independents, have moved on immigration.

The responses by Bush and Reagan in a 1980 televised debate sound like today’s Democrats. The exchange was prompted by a two-part question from an audience member: should “the children of illegal aliens… be allowed to attend Texas public schools free? Or do you think that their parents should pay for their education?”

Bush was first to reply, beginning, “I’d like to see something done about the illegal alien problem that would be so sensitive and so understanding about labor needs and human needs that that problem wouldn’t come up. But today if those people are here, I would reluctantly say I think they would get whatever it is—what the society is giving to their neighbors.”

He continued, saying undocumented immigration needed solutions and offering some.

“But the problem has to be solved,” Bush said. “Because as we have made illegal some kinds of labor that I’d like to see legal, we’re doing two things. We’re creating a whole society of really honorable, decent, family-loving people that are in violation of the law. And secondly, we’re exacerbating relations with Mexico. … These are good people, strong people—part of my family is Mexican.”

Bush went even further, saying that immigrant children should not be criminalized.

“The answer to your question is much more fundamental than whether they attend Houston schools, it seems to me,” he said. “I don’t want to see a whole… [generation]—think of six- and eight-year-old kids being… uneducated and made to feel that they’re living outside the law. Let’s address ourselves to the fundamentals.”

When Reagan’s turn to speak came, the former two-term California governor did not disagree, but said he wanted to “add to that.”

“I think the time has come that the United States and our neighbors, particularly our neighbor to the south, should have a better understanding and a better relationship than we’ve ever had,” Reagan said. “And I think that we haven’t been sensitive enough to our size and our power.”

Reagan said a smart policy would address the realities of economic insecurity in Mexico and seek to make the region—Central America—more stable.

“They have a problem of 40 to 50 percent unemployment,” he said. “Now, this cannot continue without the possibility arising, with regard to that other country that we talked about—if Cuba and what it is stirring up—the possibility of trouble below the border, and we could have a very hostile and strange neighbor on our border.”

Reagan, like Bush, said a working border, not a walled divide, was the best solution.

“Rather than talking about putting up a fence, why don’t we work out some recognition of our mutual problems, make it possible for them to come here legally with a work permit,” he said. “And then while they’re working and earning here, they pay taxes here. And when they want to go back, they can go back, and they can cross. And open the border both ways, by understanding their problems.”

Both Reagan and Bush, as presidents, signed immigration legislation. Reagan granted amnesty to 3 million undocumented residents in 1986. Bush signed legislation in 1990 supporting family unification and offering “temporary protected status” for people who were fleeing from armed conflicts or environmental disasters. It also removed language allowing border agents to block the admission of “suspected homosexuals.”

At the time these laws passed, immigration reforms were controversial—but attitudes among opponents were not as hard-line as they appear to be among GOP loyalists today. In the 1990s, American attitudes toward immigration began a rightward shift more in response to the rise of conservative media than economic fears, the Stanford Humanities Review reported in 1997.

Today, President Trump’s verbal attacks against four congresswomen of color—raising the old anti-immigrant trope of “go back” to where they came from—boosted Trump’s favorability by 5 percentage points among Republicans, a Reuters poll found, but that remark saw his support drop among independents and Democrats.

“Among independents, about three out of 10 said they approved of Trump, down from four out of 10 a week ago,” the Reuters poll said. “His net approval—the percentage who approve minus the percentage who disapprove—dropped by 2 points among Democrats.”

Other recent polls found that record numbers of voters are saying that immigration is the top issue facing the country—“the highest Gallup has ever measured for the issue since it first began recording mentions of immigration in 1993.”

But, crucially, that was only 23 percent of those polled by Gallup. “Americans still view immigration positively in general, with 76 percent describing it as a good thing for the country today and 19 percent as a bad thing,” its report on a mid-June poll said. A July report by the Pew Research Center noted that the number of “unauthorized immigrants” had fallen by 14 percent in the past dozen years (from 12.2 million to 10.5 million)

President Trump’s immigration stances are notably less tolerant than those taken by his Republican predecessor—Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. While the core of the GOP base today is embracing Trump’s virulent politics, it is also true that his race-based fulminations and cruel border enforcement are alienating independents and Democrats previously supporting him.

Trump’s dominance of the GOP may be growing. But the GOP is increasingly representing a shrinking share of the electorate. There is no room in Trump’s GOP for the immigration policies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, which, ironically turns one of Reagan’s most famous quotes upside down.

“I didn’t leave the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party left me,” the conservative icon famously said. On immigration, Reagan—and Bush—are back with the Democrats.

Steven Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He has reported for National Public Radio, Marketplace, and Christian Science Monitor Radio, as well as a wide range of progressive publications including Salon, AlterNet, the American Prospect, and many others.

This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute.