By Sophie Quinton, Stateline.org (TNS)

WASHINGTON — Ali Sinicrope and her husband would like to buy a house, but they’re not sure they can afford it. They’re public school teachers in Middletown, Conn., and they owe $80,000 in student loans.

“It just adds up,” Sinicrope, 40, said of the $600 monthly payment her family strains to make. “That’s less money, now, that we can save toward a house, that’s less money that we can put toward our kids’ college tuition.”

Connecticut lawmakers want families like the Sinicropes to spend less on student loan payments and more on everything else. Starting next year, the state will offer a refinancing program that will allow some borrowers to save money by lowering the interest rates on their loans.

“The burden of this debt is a real millstone around the neck of our economy, and we need to address it,” said state Rep. Matt Lesser, a Democrat who represents Middletown. Almost 18 percent of Connecticut residents who have a credit file have student debt — $31,100, on average, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Although the federal government dominates the student loan market, there’s much states can do to help borrowers who are struggling.

States have long recruited doctors, dentists and teachers to underserved areas by promising to forgive or repay their student loans. Now, some states are establishing refinancing programs. Connecticut has gone further this year. Not only did Democratic Gov. Dannel Malloy sign a law creating a refinancing program, he also signed one that laid ground rules for student loan servicers and created a student loan ombudsman’s office that will advise borrowers.

Such efforts won’t stop college costs from rising. The University of Connecticut’s trustees meet this week to decide whether to raise tuition by 31 percent over four years. The state flagship says it needs to boost tuition partly to offset reductions in per-student state funding.

Lesser said lawmakers need to find ways to fund state higher education systems and slow tuition growth. But for many Americans, he points out, the damage already has been done.

Nationwide, Americans owe about $1.3 trillion in student debt. Last year, 35 percent of student debt was held by borrowers over age 40, according to the New York Fed.

Most Americans rely on student loans to pay for bachelor’s degrees and graduate studies. In 2011, 68 percent of students who have been in college for four or more years reported having taken out a student loan — primarily federal loans, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

A generation ago, many Americans got their federal student loans through states. Almost every state had an office that issued federally guaranteed loans. After the U.S. Department of Education began issuing loans directly in 2010, some state student loan authorities closed their doors.

Eighteen states, including Connecticut, still issue student loans through their own student loan authorities (or in North Dakota’s case, a state bank), according to the Education Finance Council, a trade group. State agencies generally finance their loans by selling low-interest, tax-exempt bonds.

Rhode Island’s student loan authority (RISLA) developed a refinancing program after listening to borrowers, said Charles Kelley, the agency’s executive director. People kept asking if there was anything the agency could do to reduce the interest on their loans, in the same way that banks can reduce the interest rate on a mortgage when interest rates fall, he said.

It’s hard to get a better deal on a loan than a subsidized, federal undergraduate loan. Right now, they’re available at a 4.29 percent interest rate, and the federal government pays the interest while borrowers are in school. Loans for graduate students are pricier, as are federal parent loans. Private loans can be expensive, as can older federal loans, issued before the financial crisis.

“We had people coming to us with federal parent loans that were 7.9 or 8.5 percent fixed,” Kelley said of the interest rates he saw. Borrowers with old loans issued by the Rhode Island agency also wanted to know if they could refinance.

RISLA launched its program 18 months ago. So far, the authority has refinanced loans for 349 borrowers, primarily people who live in Rhode Island or went to college there. For now, it’s paying for the program with taxable bonds.

Lauren, a Rhode Island teacher who didn’t want to disclose her last name because she’s revealing personal financial information, refinanced a private student loan through the program last year. “I’ve been repaying for seven years,” the 29-year-old said of her debt. She chose the lowest-cost option: a five-year loan that can have an interest rate as low as 4.24 percent.

Seven states had approved or piloted a student loan refinancing program as of November, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. The U.S. Treasury Department cleared the way for more states to adopt such a program last month, when it approved the use of tax-exempt bonds for student loan refinancing.

For states that already have a student loan program, setting up a refinancing program costs next to nothing. RISLA didn’t need legislative approval to get started. Connecticut’s program, created by law earlier this year, will begin with a pilot funded by transferring $5 million from one of the student loan authority’s subsidiaries.

©2015 Stateline.org. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

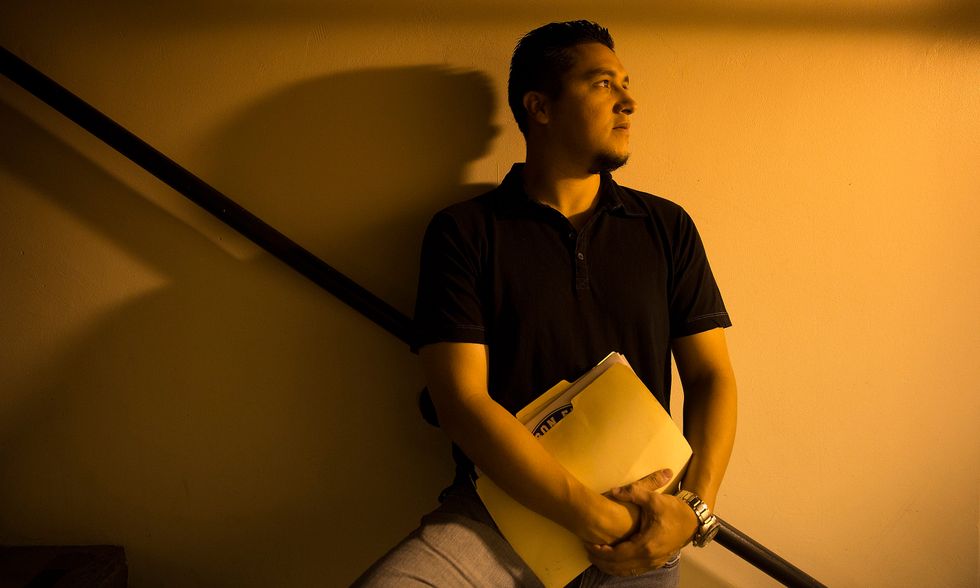

Photo: Jorge Villalba poses for a portrait on Sept. 3, 2015 in Encino, Calif. Villaba is struggling to pay off student loan debt. (Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times/TNS)