Post-Recession Quietude Unites Californians, Bolsters Governor Brown

Mark Z. Barabak, Los Angeles Times

SALINAS, Calif. — Tony Salameh and Danielle Clark weathered the Great Recession from two worlds just a few miles apart.

Salameh, 62, owns several restaurants in Carmel, the wealthy hamlet perched like a small jewel overlooking the sea.

After a significant falloff, business is about where it was five or six years ago. Salameh’s bottom line, though, is a third what it used to be; tourists are back in force, but they order lamb sliders or spring rolls instead of a meal to accompany their $10 and $12 cocktails.

Clark, 38, is an office manager who commutes to a local vineyard from nearby Salinas, the flat, drab portal to California’s vast agricultural valley. Her fiance lost his advertising position in the downturn and after three years of unemployment landed two jobs: caring for an autistic child and working weekends as a bouncer at a local club. His combined income, however, is less than what he made before the recession, so the couple remain watchful of their wallets.

“You walk gingerly because when you’ve had the rug pulled out from under you, like we all have, you’re tentative,” Clark said, pausing as she addressed boxes at a post office. “I’m still kind of holding my breath. The security that I felt — and maybe it was a false sense of security before this all happened — I no longer feel.”

Despite their stations, Salameh and Clark share a similar outlook, a mix of tempered optimism and low-grade anxiety that reflects the mood of California early in this election year. “People are afraid to spend,” Salameh said, as sunlight danced off a fountain in the courtyard of his Anton & Michel restaurant. “People are still worried we might have another crash.”

After a raucous decade marked by incessant elections and an unprecedented recall that turned a Hollywood action-hero into governor, California has settled into a period of rare political quietude. A severe drought has gripped the state. But the battles over immigration and affirmative action have receded, if not entirely ended. The budget is not only balanced but showing a surplus of several billion dollars.

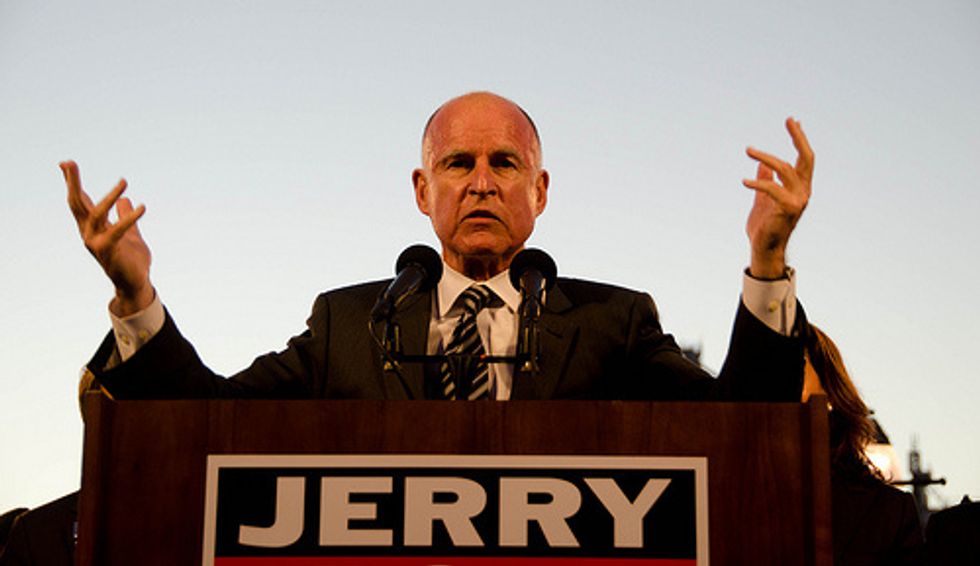

Governor Jerry Brown, who seemed so captivatingly kooky during two terms starting in the 1970s, has become the very model of buttoned-down sobriety. Bidding for an unprecedented fourth term at age 75, the Democrat is an overwhelming re-election favorite, though he has yet to declare his candidacy.

Beneath the surface calm, however, is a stomach-fluttering sense that the Great Recession has changed California in some fundamental way, unlike other periods of boom and break that have been the state’s life cycle since the Gold Rush days. Things are getting better, many say, but they aren’t great and it’s not certain they will keep improving, or ever get back to where they were.

“We may be back on our feet,” said Pete Realmuto, 55, who owns an upscale Carmel women’s boutique, “but it’s not landing in the same spot.”

In his recent state of the state address, Brown touted California’s economic turnaround and the 1 million jobs created since 2010. But millions are still living in poverty — by some accounts, the highest rate in the country — and the recovery has been decidedly uneven. Cities and suburbs on or near the coast are rebounding — the more so the closer they are to San Francisco or Silicon Valley — while double-digit unemployment remains the norm across much of the interior.

The contrast is plain here in Monterey County, which has long been divided economically by the so-called Lettuce Curtain.

The peninsula, a leisure playground, boasts world-class tourist attractions, high-end resorts, trophy golf courses, breathtaking scenery and what, for many, are second or even third homes. A sign at a Carmel real estate office advertises properties at $4 million or more in one window and “our most affordable homes,” starting at $700,000 and soaring past $1 million, in the other.

The Salinas Valley, less than 20 miles away, is blessed with richly fertile soil but few of the other gifts nature can offer. When the outside world looks in, it is often for the wrong reasons: Salinas’ chronic gang violence, or the struggle to keep libraries and booksellers afloat in the place where John Steinbeck was born.

The agriculture industry helped ease the hardship of the recession — even in bad times, people still have to eat — but the downturn hit hard. Many of the service workers who live in the valley and commute to the peninsula lost their jobs when tourism tapered off and people quit dining out. Home values plunged and remain far below their peak.

“If there’s a recovery, I don’t see it,” said Star Martinez, 50, a manager at the county welfare office in Salinas, which remains filled with people applying for food stamps or who’ve lost their homes.

Although unemployment has dropped to 4.9 percent in coastal Monterey and 4.1 percent in neighboring Pacific Grove, from a recession high of 8.3 percent and 7 percent, respectively, it has only ticked down slightly in Salinas, to 15.5 percent from 17.7 percent. The December jobless rate was 8.3 percent statewide.

Photo: Steve Rhodes via Flickr