Voters Reject 'Slavery,' But Prisons Still Treat Human Beings Like Chattel

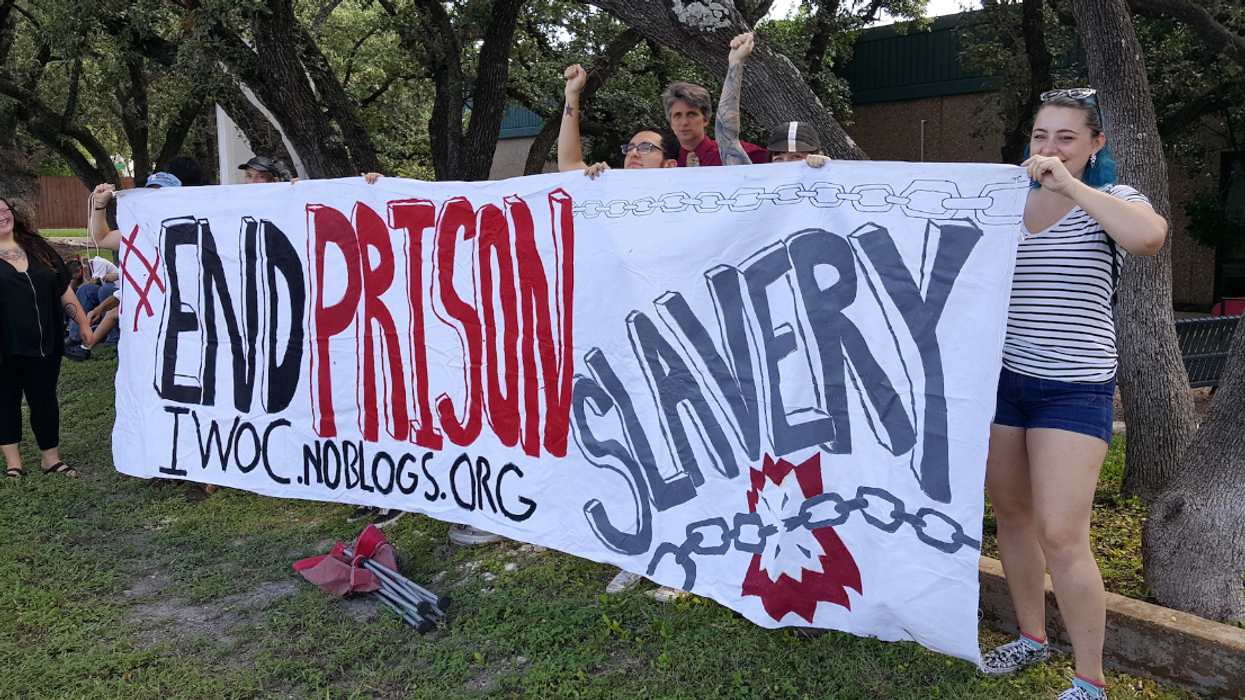

On November 8, many Americans rejected the idea of slavery: Voters in Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont all agreed to change the language in their state constitutions to close so-called “slavery loopholes” — small phrases that permit forced labor in the case of criminal convictions. Louisiana’s electorate rejected the change after the ballot measure’s initial sponsor noted that the proposed substituted language could actually backfire and expand forced labor.

This year wouldn’t be the first time the United States congratulated itself for sidestepping slavery while still treating human beings like property. The "Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves" took effect in 1808 and made it illegal for Americans to engage in the slave trade between nations. So prohibited was importing slaves that Congress gave U.S. authorities the right to seize ships they caught transporting slaves and confiscate their cargo, which, at the time, was a form of shorthand for the word "people."

But the anti-slavery act allowed intra-national slave trade, sometimes called “coastwise” trade. Not only did it allow the trade, it insisted traders document the departure and the arrival of every slave at each of the nation’s ports. Court records and ship manifests reveal that approximately 71,000 slaves were exchanged throughout the country between 1819 and 1861.

And all the while, citizens considered this at least a quasi-abolitionist country. Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the Confederates States of America said in 1861 that “The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us…”

Stephens was obviously wrong since another question about our peculiar institution required an answer in the form of the Emancipation Proclamation years later.

But one piece of that particular institution endures and shows no signs of slowing or even awareness among the public is the way wardens traffic their wards on an open corrections market, selling and swapping them like they’re toys or tillers.

That is, the same bartering of human beings continues today everywhere in this country but West Virginia. Wardens and administrators trade prisoners between 49 states — and courts don’t consider it anywhere near unlawful.

The United States Supreme Court expressly authorized this type of interstate bazaar in 1983 when it held that the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment offered a Hawaiian prisoner no liberty interest — an individual freedom inherent in theories of constitutional liberty if not specifically enumerated by law — that would prevent his being shipped off the island to a California prison 2425 miles and a Pacific ocean away for the rest of his life, as he served a sentence that guaranteed he would never make parole.

That holding in Olim v. Wakinekonahas endured for almost 40 years and lower courts have interpreted it as holding that a state inmate has no legal right to be housed during his incarceration in his home state. Federal prisoners can be housed in any federal facility across the country, although the FIRST STEP Act, the federal reform legislation signed by former President Donald Trump in 2018, limited how far away the Bureau of Prisons could move an inmate from his home to 500 driving miles.

Since the Supreme Court sanctioned the sale of human beings, about 20,000 prisoners have been traded, for a price of about $76 per day, according to original research conducted by New York University School of Law’s Associate Professor of Law Emma Kaufman.

Gillian Brockell, a writer for Retropolis, the Washington Post’s history blog, notes: “Most Americans think of slavery as the inherited chattel form that existed in the United States from 1619 to 1865.” If that’s what slavery is, then it’s unclear why swaps and trades, where the nature of the transaction is one of ownership, of clean, unchallenged title, don’t cause these citizens to blow a gasket.

Treating prisoners like property has become common and accepted through international prisoner swaps. One day after voters in four states rejected the slavery loophole, President Joe Biden said he thinks Russian president Vladimir Putin will become more amenable to an exchange between the countries, one where Russia trades WNBA player Brittney Griner and former United States Marine Paul Whelan for someone (or someones) held by the United States.

This type of prisoner swap evokes chattel slavery more than prison labor does. A nation-state acts as if it owns the person in custody and can alienate him for a price. A prisoner swap almost always results in the pawns’ freedom, so few people object to the process even if they dislike who’s being traded.

But prisoners who are traded within the country see no such emancipation at the ass-end of their deals. Updated records of their sales and movements, unlike the coastwise slave trade 160 years ago, are spotty or tightly controlled. It’s unclear exactly how many people get traded every year, where they go, or how much money changes hands over this practice.

Not only is shipping inmates out immoral, it may be illegal. The reason why the state of West Virginia bans prisoner trades is that they violate state law on banishment, a punishment that James Madison, the United States’ fourth president and author of The Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, said was the one of the severest. Constitutions in 15 more states ban it and appellate courts in many more invalidate criminal sentences requiring removal from the jurisdiction.

The prisoner trade is also harmful. Regular contact with family tends to reduce recidivism among inmates, but it can cost a lot to make the trek. When prisoners move further away, families must spend even more to be able to visit them.

Part of prison management is moving bodies around. But keeping some of them hither while sending others thither and yon for a price isn’t a best correctional practice. It’s not even clear if it's legal.

But no one’s voting on any of this.

Regardless of what states do to their constitutions or Congress does to the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, slavery’s still alive in American prisons — but it’s not because inmates swing a mop for 75 cents per day.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.

- Behind Anti-Slavery Ballot Measures, Prison Labor Isn't So Simple ›

- Why Didn't Justice Department Defend Alabama Prisoners From Starvation? - National Memo ›