WASHINGTON — You probably think there is a big struggle over the Democratic Party’s soul and the meaning of progressivism. After all, that’s what the media talk about incessantly, often with a lot of help from the parties involved in the rumble.

Earlier this month, Gov. Jack Markell of Delaware, a proud Democratic centrist, published a thoughtful essay on The Atlantic‘s website under a very polemical headline: “Americans Need Jobs, Not Populism.” Take that, Elizabeth Warren.

The Massachusetts Democrat is clearly unpersuaded. In a powerful speech to the California Democratic Convention last weekend, she used variations on the word “fight” 21 times. “This country isn’t working for working people,” Warren declared. “It’s working only for those at the top.” If populism is a problem, Warren has not received the message.

There’s other grist for this narrative. Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel was re-elected earlier this year only after a spirited battle during which his opponent, Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, labeled him “Mayor 1 Percent.” And every other day, it seems, there’s a report about Hillary Clinton being under pressure either to “move left” or to resist doing so.

A storyline doesn’t develop such a deep hold without some basis in fact. There are real dividing lines within the center-left around issues such as the right way to reform public education and the best approach to public employee pension costs. There’s also trade, a matter that has so vexed Democrats that for many years, its presidential candidates have tried to hedge the issue — usually during the primaries but sometimes until after the election.

But the us-vs.-them frame on this debate has two major problems. The first affects the center-left itself, something shrewd Democrats have started to notice. A post on The Democratic Strategist website in March argued that “slinging essentially vacuous stereotypes like ‘corporate centrists’ and ‘left-wing populists'” inevitably leads to “a vicious downward spiral of mutual recrimination.”

The larger difficulty is that the epithets exaggerate the differences between two sides that in fact need each other. There is political energy in the populist critique because rising inequality and concentrated wealth really are an outrage. But the centrists offer remedies that, in most cases, the populists accept.

Both Markell and Warren, for example, have emphasized the importance of business growth and job creation. In her California speech, Warren described the need for policies that foster prosperity while “bending it toward more opportunity for everyone.” Her priorities were not far from those Markell outlined in his article.

There was nothing exotically left wing about Warren’s call for “education for our kids, roads and bridges and power so businesses could grow and get their goods to market and build good jobs here in America, research so we would have a giant pipeline of ideas that would permit our children and grandchildren to build a world we could only dream about.”

For his part, Markell freely acknowledged that “the altered economic terrain is preventing new wealth from being broadly shared,” that “income inequality is growing worse,” and that “a huge number of Americans are economically insecure.” Growth is “necessary, but not sufficient,” and he made the case for “a decent minimum wage,” “affordable and quality health care,” and support for a dignified retirement.

Sen. Warren and Gov. Markell, would you kindly give each other a call?

As for Emanuel, his inaugural address on Monday was devoted to the single subject of “preventing another lost generation of our city’s youth.” It was a powerful and unstinting look at how easy it is for the rest of society to turn its back on those for whom “their school is the street and their teachers are the gangs.”

“The truth is that years of silence and inaction have walled off a portion of our city,” he said. “It is time to stop turning our heads and turning the channel. … We cannot abandon our most vulnerable children to the gang and the gun.” If “centrists” and “populists” can’t come together on this cause, they might as well pack it in.

Yes, the populists and centrists need to fight out real differences, and that’s what we will see in the coming weeks on trade. But they would do well to remember the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr’s observation that it’s always wise to seek the truth in our opponents’ error, and the error in our own truth.

And as it happens, to win the presidency, one of Hillary Clinton’s central tasks will be to move both sides in the progressive argument to embrace Niebuhr’s counsel.

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com. Twitter: @EJDionne.

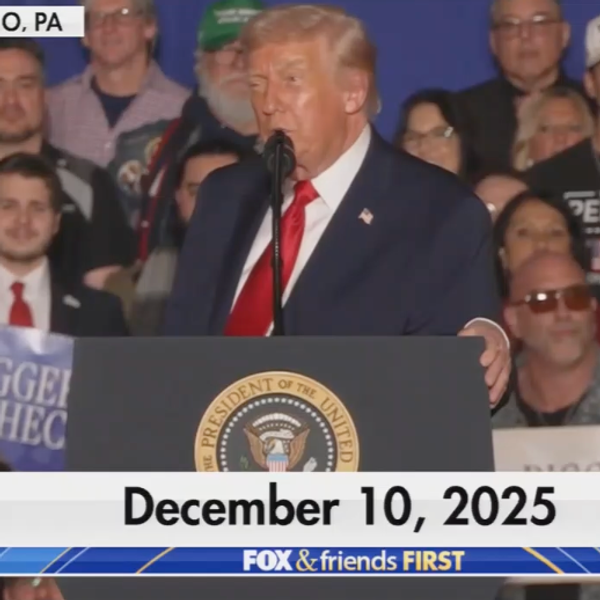

Photo: Elizabeth Warren campaigning in 2012. (Jacqueline via Flickr)