The rise of antibiotic-resistant pathogens — so-called “superbugs” — has outpaced development of new drugs to treat them, posing a severe public health crisis. But a recently discovered antibiotic named Teixobactin may signal a promising new era in drug development, according to findings published in the journal Nature last week.

In the 1940s, the first generation of mass-produced antibiotics, such as penicillin, had a profound impact on medicine and public health in the developed world, greatly reducing illness and death from a wide swath of infectious diseases. The organisms that antibiotics were designed to kill evolved over time, however, leading to increasingly drug-resistant strains of bacteria that became more lethal and more difficult to treat. According to the CDC, these antibiotic-resistant bacteria infect at least 2 million people in the United States annually, 23,000 of whom die as a result. In a report released last spring, the World Health Organization warned that a “post-antibiotic era — in which common infections and minor injuries can kill — is a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

Compounding the severity of the crisis, the creation of new antibiotics has all but stopped. Antibiotics are developed by cultivating naturally occurring chemicals that microorganisms produce in order to attack each other in an unending battle for natural resources. Scientists estimate that of all the antibiotic compounds that exist in nature, 99 percent of them cannot be cultivated in a laboratory setting. Most of the remaining 1 percent were mined by the 1960s, and novel antibiotics have been in shorty supply ever since, creating a stalled pipeline for research and development of new drugs.

In 2002, researchers at Northeastern University began working on a new method of cultivating these finicky microorganisms. The iChip, which represents the culmination of over a decade of labor, is a two-inch-long device that scientists stick in microbe-rich mud, yielding tremendous results. The chip isolates the microbes that exist in samples of diluted dirt into distinct holes, and then sandwiches those samples between permeable membranes that allow bacteria to flourish in their natural habitat — the muck. According to the Nature report, the “growth recovery by this method approaches 50 percent,” making it 50 times more efficient than soil cultures grown in petri dishes. It was through this method that scientists discovered Teixobactin.

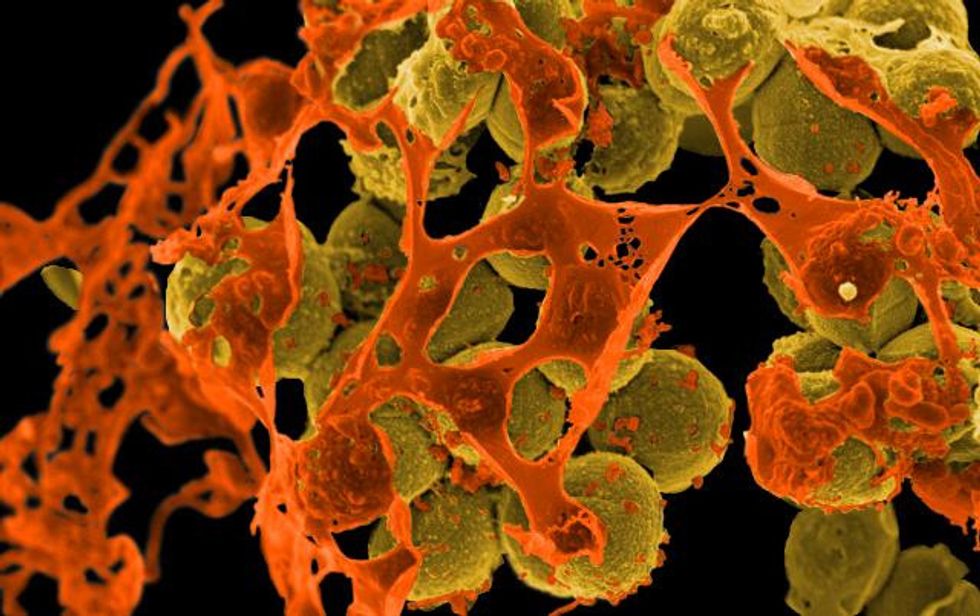

As of now, Teixobactin has only been tested in mice, but the results have been encouraging. It has been shown to stop common bacterial infections, as well as drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis and staph, with no apparent side effects. While most antibiotics work by attacking proteins, Teixobactin takes a different, more effective tack: it shuts down the processes by which bacteria erect their cell walls. This kills microbes quickly, and the DNA that codes the building of cell walls is less likely to mutate than the genes that direct protein creation. All this greatly fortifies Teixobactin against the possibility of bacteria developing a resistance against it.

Human trials of the drug are unlikely to begin for at least two years. Still, the success of the new iChip technology and the early success shown demonstrated by its discoveries point to a brighter future in the battle against superbugs. For new antibiotics, it will be a long road from the dirt to the drug store, but this is a monumental first step.

Photo: NIAID via flickr