This is for four women who are not here.

It is for grandchildren who never existed and retirement celebrations that were never held. It is for Sunday dinners that were never prepared in homes that were never purchased. It is for children who were never born and fathers who never got to walk daughters down the aisle. It is for mortarboards that were never flung into the air, for first kisses that were never stolen, for dreams that ended even as they still were being conceived.

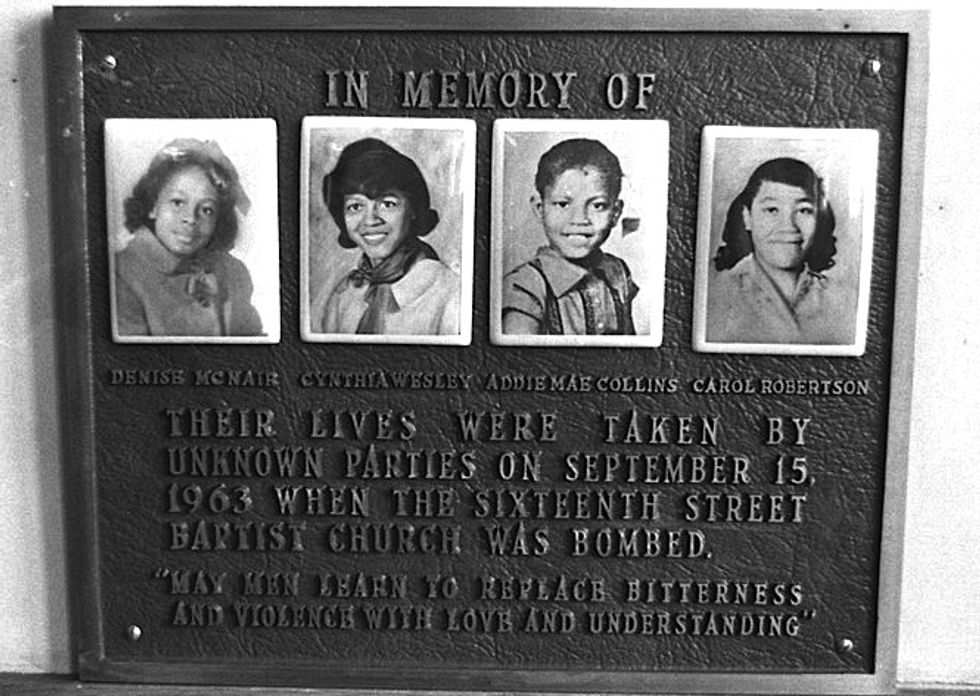

This is for four little girls who died, 50 years ago today.

Died. It is, in this context, a misleading word. Makes it sound as if maybe 11-year-old Denise McNair and 14-year-old Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley and Carole Robertson succumbed to some disease. Hearing it, you might not realize they died because terrorists planted a bomb beneath an exterior stairway of their church and that it exploded while they were in the basement preparing for Sunday school. You might not realize that a chunk of concrete embedded itself in one child’s skull or that another child’s head was torn from her body.

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL, had been the nerve center of a human rights campaign that made the city notorious the previous spring, the place from which nonviolent armies poured to face snarling dogs and high-pressure hoses under the command of Police Commissioner Bull Connor. Because this was what you had to do if you were African-American and wanted to drink from a clean public fountain, try on clothes in a department store or buy a hamburger at a lunch counter in Birmingham.

The marchers won that battle and their movement was at a summit of hope by the time it convened in Washington to march in support of federal legislation. “I have a dream today!” the great man roared, and it must have felt, on that transcendent day, as if that dream shimmered at the very verge of reality.

Eighteen days later, the bomb exploded at 16th Street Baptist, where the Sunday school lesson was to have been “The Love That Forgives.” And the summit of inspiration gave way to a yawning abyss of despair.

At a funeral for three of the little girls — Carole’s family buried her separately — the great man sought to find the message in their deaths. This tragedy, he said, should challenge preachers who meet hatred with silence, politicians who use it to buy votes, a federal government that compromises with conservative hypocrisy and African-Americans who passively accept status quo.

He preached against despair and loss of faith. But he also let slip something that suggested how deeply even he, Martin Luther King, a mighty preacher of the Christian gospel, was shaken by this event. “Life is hard,” he said, “at times as hard as crucible steel.”

Indeed. Just when you think you know the depths to which people can sink, the extremes to which they can go in their sheer, pathological hatred, something happens that takes your breath away.

That’s what that day did. The martyrdom of four little girls made a nation question its conscience — What kind of people kill children in church? — and so, helped turn the tide toward freedom. Congress said as much last week in awarding them its Gold Medal.

But to consider America 50 years later, still swathed in its tribalism, proud in its manifold hatreds, righteous in its denials, is to be reminded that tides are not permanent. They ebb and flow. And the battle to make America live up to the first sentence of its founding document — the one about the “self-evident” truth of equality — is ever ongoing.

“Change” King once said, “does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Such struggle is the price of freedom.

And a debt we owe four women who are not here.

(Leonard Pitts is a columnist for The Miami Herald, 1 Herald Plaza, Miami, Fla., 33132. Readers may contact him via email atlpitts@miamiherald.com.)

Photo: Birmingham News, File