A study published Monday by the Sunlight Foundation suggests that interest groups, not individual voters, are the primary catalysts of policy change in American government. Michigan State University political science professor Matt Grossmann studied “790 significant domestic policy changes” occurring since 1945, and found that interest groups were more likely to motivate change than “public opinion, research, events, ideas, the media or courts.”

These findings come as little surprise in light of recent research indicating that in the hierarchy of influence on policy decisions, average voters come dead last. However, Grossmann’s study differs slightly in his findings of which group exercises the most power.

Last month, Princeton University released a study entitled “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens” that quickly went viral and was rebranded in the headlines as “America Is An Oligarchy.” While this study also determined that average citizens had the least amount of impact on the government, it also claimed that businesses and other economic elites carried the most sway, and that mass-based interest groups were largely ineffective in influencing policy.

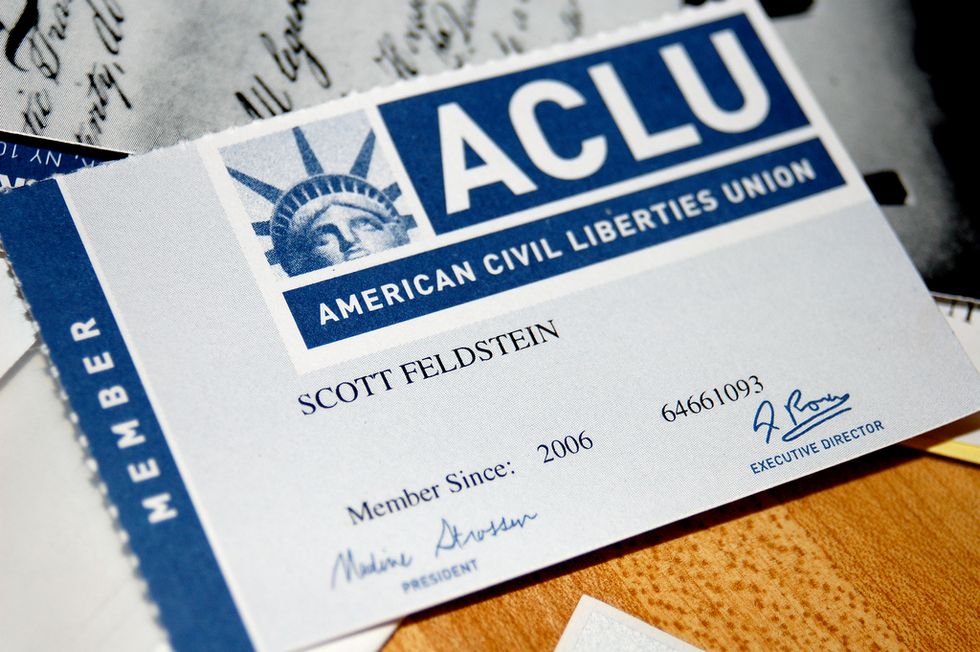

But in Grossmann’s new study, he manages to restore a little faith in the effectiveness of advocacy groups that are meant to represent public interest, not just the economic affairs of big business. According to Grossmann’s work, “The interest groups credited with policy changes most often since 1945 were the AFL-CIO, the NAACP, the U.S. Conference of Mayors and the ACLU.”

For Grossmann, influence is indicated by successful policy change. Businesses, according to the Princeton study, tend to advocate for the status quo, and oppose policy change. As such, though their opposition is effective, it is not responsible for affecting actual change, but rather for simply maintaining existing conditions.Therefore, big business and its interest groups tend to stymie policy change, rather than encourage it.

The Princeton study also failed to include a variety of interest groups and advocacy groups, only taking into consideration five generally conservative interest groups and “only two of the top 28 advocacy groups,” as indicated by policy historians.

Regardless of their differences, both studies found that organized action and large groups were far more influential in policy decisions than individual voters, which as the Princeton study suggests, de-legitimizes a Majoritarian Electoral Democracy or Majoritarian Pluralism as the structure of the American government.

These results also further corroborate another recent study conducted by professors at Yale and the University of California, Berkeley which determined that campaign donors received better access to their politicians. The study provided statistical support for the previously unproven (though largely held) belief that “financial resources translate into political power.”

This finding is raising increasing concerns into the influence of wealth in today’s political scene, particularly in light of the Supreme Court’s recent decisions to further loosen limitations on campaign contributions. As individuals are able to contribute more and more to candidates and campaigns, it seems that the rule of the economic elite may be almost inevitable.

However, Grossmann’s study made one more interesting discovery that may quell these fears. According to Grossmann, although the number of lobbyists and organizations (and therefore money in play) has skyrocketed, with the amount spent on presidential elections consistently on the rise since 2000, interest group influence has not increased in parallel.

Chart via Sunlight Foundation/Matt Grossmann

Moreover, when comparing the effects of business interest to that of advocacy groups and public interest groups on policy change, the latter two were more influential in 9 out of 14 policy areas, whereas business was more effective in predictable industries, including finance and commerce, science and technology, and macroeconomics.

Chart via Sunlight Foundation/Matt Grossmann

So while the United States certainly isn’t the sort of democracy that we might imagine it to be, Grossmann still manages to make the argument that the best interests of the people continue to be represented in Washington –even if not by way of individual votes.

Photo via Flickr