Alex Gibney’s documentary Going Clear, which probes into the notoriously opaque and controversial Church of Scientology, aired on HBO Sunday night to an eruption of positive reviews and social media exultation.

In weighing the relative merits of the film and the assiduously researched book upon which it is based, one moment from the movie stands out for its cinematic impact: Scientology leader David Miscavige, standing alone in the center of a stage in the Los Angeles Sports Arena, before an audience of 10,000, exclaiming: “The war is over!” while fireworks explode all around him.

The “war” Miscavige refers to is the 26-year campaign waged by the church against the IRS, using private investigators to discredit the agency and inundating it with litigation. The aim and result of these efforts was to coerce the IRS into recognizing Scientology as a religion and therefore granting its several dozen entities tax-exempt status.

For nearly three decades, the IRS claimed that the church operated and behaved like a business. For any organization, such as a religious institution, to qualify for 501(c)3 status, its “net earnings may not inure to the benefit of any private individual,” a condition not exactly affirmed by the lavish lifestyle of Miscavige or the several highly valuable gifts that the church has bestowed upon its most prominent member, Tom Cruise. Compounded with the long, troubling list of allegations against the church, these facts have led many to suggest that Scientology is not only undeserving of tax exemption, but is simply not a real religion at all. Which only raises the question: When does a religion become “real”?

The First Amendment precludes the U.S. government from privileging any religion; there is no status the state is supposed to confer that validates a faith. Tokens of official recognition for a religion are somewhat scattershot. In 2007, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs began to allow the Wiccan pentacle symbol on veterans’ tombstones, after a 10-year dispute; states permit participants of any number of practices to officiate religious ceremonies that result in legally binding marriages. But tax-exempt status arguably has become the strongest government imprimatur of a religion’s legitimacy. The onus has fallen on the taxman to decide when a religion becomes, for lack of a better word, “real.” As Lawrence Wright, the author of Going Clear, put it in a recent interview with Salon, it’s somewhat incongruous that the IRS is the “only agency empowered to make this distinction,” since it’s “not exactly stocked full of theologians.”

But the 1993 granting of tax-exempt status solidified Scientology’s claim to legitimacy. The State Department had been mum on the issue of religious discrimination against Scientologists abroad, but once the IRS made its determination, that all changed. Beginning in 1993 and continuing into the most recent report, the department mentioned in its International Religious Freedom Report that German state and federal government agencies maintain policies that exclude and diminish the church and its members. The German government continues to maintain that Scientology is a commercial enterprise, not a religion, just as the U.S. did for nearly 30 years.

The IRS cannot make its determinations based on how silly a belief system may or may not be. The agency is given latitude to investigate the church’s assets and organizational structure, but interrogating the wisdom and logic of any faith or practice is outside its purview. In trying to establish whether or not a purported religion is a fake, it is unavailing to examine the ridiculousness of the doctrine. Of course, this doesn’t mean there aren’t scams.

In an especially colorful recent example of fraud, on March 10 a church in Panama City, FL, called The Life Center: A Spiritual Community had its tax-exempt status revoked after officials discovered the church was operating a nightclub called Amnesia: The Tabernacle on the premises. The nominal church, situated in a tax-exempt building, hosted all-night lingerie parties and an event called “Wet ‘n Wild,” which was advertised as “white water meets Tabernacle PCB with a little twerkin’,” according to reporting by the Panama City News Herald. Would-be religions are rarely so unequivocally false. (It’s possible — though admittedly highly dubious — that the church might have squeaked by, had Amnesia claimed nightly raves were part of its sacred practice.)

While tax-exempt status demonstrates government recognition, a religious organization that doesn’t have it is by no means precluded from receiving the same protections and rights granted to those that do. The Church of Satan is not tax-exempt as a matter of preference (so they claim), choosing instead to adhere to founder Anton LaVey’s conviction that all churches should be taxed to “remove the government sanction of religion,” a position shared by other LaVey-influenced sects. (At least one Satanist sect, Satan’s Chapel, is tax-exempt.)

Yet regardless of tax-exempt status, the rights of several different sects of Satanism to practice have been recognized in a wide swath of court decisions. For instance, in 2014, the Satanic Temple (yet another group) won the right to erect a statue of Baphomet on Oklahoma state grounds after a Christian group was allowed to place a Ten Commandments monument in front of the state capitol building.

As for Scientology, the film won’t necessarily enlighten anyone who has read Wright’s book, or any of the other journalistic exposés of the last decade or so. If you need a refresher on Scientology’s risible theology, the South Park episode “Trapped In The Closet” offers an arguably more cogent, and certainly more entertaining, explanation. But Gibney’s documentary draws its considerable power from the personal narratives of several apostates, some of whom worked in the church’s highest echelons, whose disclosures form the film’s backbone.

And in another neat trick that only a movie can pull off, Gibney juxtaposes archive footage of church executives denying the accusations leveled at Scientology with new interviews of those same former executives, contrite and owning up to the church’s deceptive practices. The meaning is clear: Whatever Scientology is, it is not what it claims to be.

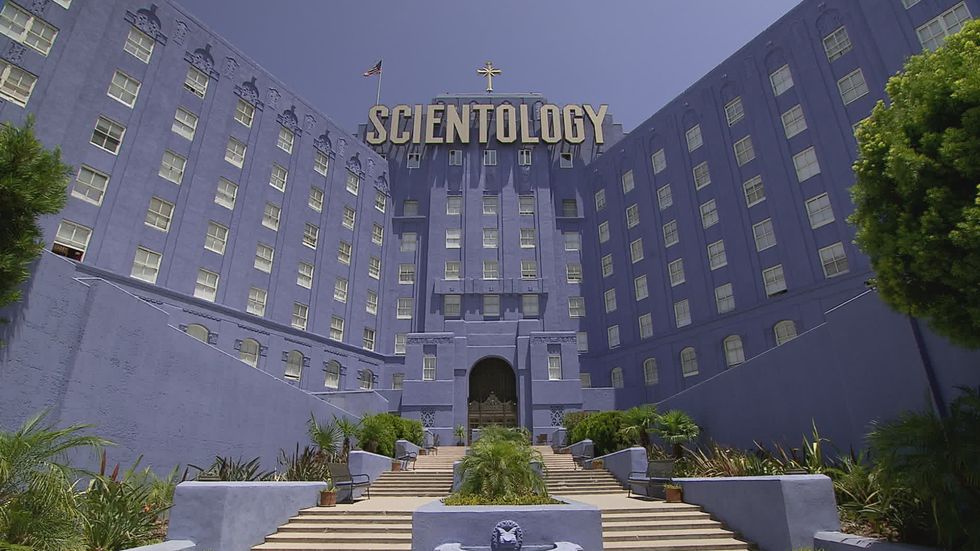

Photo courtesy of HBO