By Jim Puzzanghera, Los Angeles Times, (TNS)

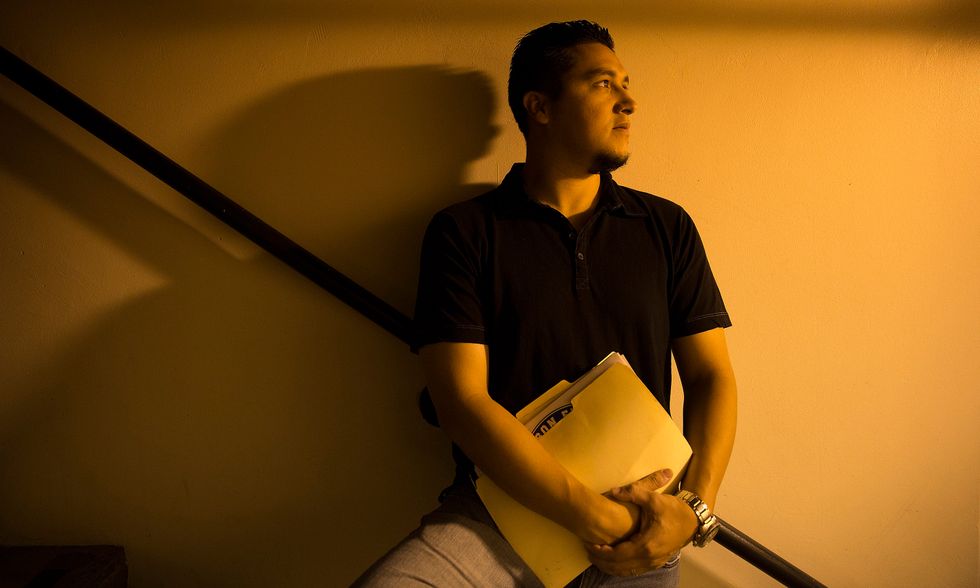

WASHINGTON — Jorge Villalba was a construction worker when the housing market began slowing in 2005, so the Glendale, Calif., resident changed jobs and decided to invest in his future by going to college.

So far, the investment hasn’t paid off.

Villalba, 34, owes $158,000 in student loans for his four-year degree in multimedia, 3-D animation and graphic design at ITT Technical Institute. He isn’t earning enough to keep up with the payments, so the amount keeps rising with interest.

He figured he’d get a great job and pay off the loans.

“It hasn’t happened that way,” said Villalba, who is married with two young children but can’t afford to move from their cramped one-bedroom apartment.

Students around the country — and often their parents — have racked up so much college debt since the recession that it now threatens the nation’s economic growth.

The debt weighs down millions of Americans who might otherwise buy homes or start businesses. And the financial horror stories of debt-saddled students, combined with continued increases in tuition, could deter others from attending college and could produce a less-educated workforce.

“The impact on future (economic) growth could be quite significant,” said Cristian deRitis, who analyzes consumer credit economics for Moody’s Analytics.

The amount of outstanding student loans has skyrocketed 76 percent to almost $1.2 trillion since 2009 as college costs have shot up and graduates have had difficulty finding good-paying jobs.

Before the Great Recession, total outstanding student loans ranked well below mortgages, auto loans, credit cards and home equity lines of credit as sources of household debt. Now it trails only mortgage debt, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

About 40 million consumers have at least one student loan, and the average debt was $29,000 last year, according to credit reporting firm Experian.

Worse for students, delinquency rates on college loans are rising even as they decline for other types of household debt.

The New York Fed found that 11.5 percent of student loans were at least three months delinquent as of June 30 — more than 3 percentage points greater than any other loan category. Unlike other debt, student loans can’t be discharged in bankruptcy.

So it’s not surprising that when Gallup asked parents this year to name their biggest financial worry, paying for their children’s college education topped the list.

“We’re essentially running a higher-education system here that is not sustainable,” said Anthony Carnevale, director of the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University. “It’s kind of a runaway train.”

The broad ramifications for the economy and the higher-education system have led some presidential candidates to propose ways to make college more affordable and reduce the debt burden, such as through refinancing at lower interest rates.

“Think of the millions of Americans being held back by their student debt,” former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton told the Democratic National Committee’s summer meeting in August. “They cannot start a business, they cannot buy a house, they cannot even get married because of the loans hanging over their heads.”

The Financial Stability Oversight Council, a panel of top federal regulators that watches for emerging economic threats, warned in its annual report this year that “high student-debt burdens could impact household consumption and limit access to other forms of credit, such as mortgages.”

Because most student loans are backed by the federal government, a rash of defaults would not trigger another financial crisis the way the mortgage meltdown did, deRitis said.

But taxpayers could take a hit, as would the economy.

“This is something that’s going to unwind over time,” he said, noting that the improving economy has caused the growth of student loan debt to ease. “It’s going to be a long, slow burn.”

Last year, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found that student debt lowered the likelihood of homeownership for a group of students who attended college in the 1990s.

Research this year by the New York Fed suggested that “a substantial portion” of the increase in young people living with their parents “can be explained by increasing student debt balances.”

To deal with the issue, Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., another Democratic presidential candidate, have made large increases in federal funding the centerpieces of their college affordability plans.

“You can win votes by saying we’re going to put a degree in every pot,” Georgetown’s Carnevale said, “but we’ve got to get down the cost.”

Average tuition and fees at public four-year colleges and universities were $9,139 in the latest school year, according to the College Board. That was up 66 percent from a decade earlier as governments hit hard by the recession cut back on college funding.

Over the same period, tuition and fees at private, nonprofit colleges and universities rose 49 percent on average to $31,231 as the schools incurred major costs in upgrading dormitories and building health clubs and other facilities to compete for students from wealthy families.

Students seeking lower-cost alternatives increasingly have turned to community colleges, where average tuition and fees rose 53 percent during the last decade.

That trend risks spreading the student loan debt problem to schools long seen as the only affordable higher education option for low-income students, said Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, director of UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute.

Meanwhile, wages have stagnated in the wake of the Great Recession. The average starting salary for a graduate with a bachelor’s degree was $48,127 last year, down from $49,224 in 2008, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers.

For-profit schools, such as ITT Technical Institute and Corinthian Colleges Inc., have exacerbated the problem. They lured students, such as Villalba, who were looking for better career opportunities in a down economy.

Villalba said most companies don’t value his degree from ITT.

He’s earning $15 an hour in a graphic design job and trying to figure out how to pay off his student loans, including some private ones with interest rates of about 20 percent.

He’s hoping for help from proposals to allow student loans to be refinanced at lower rates.

“I’m looking at 30 to 40 years to pay it off,” Villalba said of his debt. “It’s a huge burden.”

Photo: Jorge Villalba poses for a portrait on Sept. 3, 2015 in Encino, Calif. Villaba is struggling to pay off student loan debt. Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times/TNS