Cross-Posted From The Roosevelt Institute’s New Deal 2.0 Blog

Put on your monocle and top hat and pretend you are part of the 1% for a minute. Your first task is to write a set of legal codes about the collection of debt in this country, specifically student debt. And you want to be kind of a jerk about it. What’s the one thing you could do for student debt that you don’t do for any other type of debt, one that would radically shift the relationship between student loan creditors and debtors both practically and symbolically?

How about this, from the Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996: “Notwithstanding any other provision of law… all payments due to an individual under… the Social Security Act… shall be subject to offset under this section.”

What this means is that when it comes to collecting on student loans, the government can take funds from your Social Security check. There are rules to the offset: the first $750 a month can’t be touched, and only 15 percent of benefits above that can be taken to pay back student loans. But this is still a radical break in the social contract with no equivalent for private debts.

If you look at the original text of the Social Security Act, you can see that Social Security payments were not “subject to execution, levy, attachment, garnishment, or other legal process, or to the operation of any bankruptcy or insolvency law.” My man Franklin Delano Roosevelt understood that basic economic freedom, one part of which is freedom from utter poverty in old age, would come under assault from creditors and debt and that it was important to clear a space that provides a baseline of income that clever debt collectors can’t get to. Social Security is supposed to be just one leg of a three-legged stool for retirement, the amount necessary to keep poverty at bay, and it is crucial that it is protected.

Yet we are willing to snap this leg off the stool as payment for, of all things, loans people take out to educate themselves. In a dynamic economy, education should be risky — whole occupations and industries come and go with technology, and what was a wise investment at one point is a bad one later on. But there need to be rules for what happens when these risks go bad. We have removed every last rule on this kind of debt.

According to the Project on Student Debt, the average debt load for graduating seniors in 1996, when this law was passed, was $12,750. Now it is over $23,200. Also note that, post-1991 and upheld by the Supreme Court in 2005 as it regards Social Security payments, student loan collection has no statute of limitations. This is one of the very few kinds of debts without such limitations. As this site puts it, ”Creditors and debt collectors have a limited time window in which to sue debtors for nonpayment of credit card bills… In most states, the statute of limitations period on debts is between three and 10 years.” But in this case, the Department of Education notes, ”[b]y virtue of section 484A(a) of the Higher Education Act, statute of limitations of no kind now limits Department’s or the guaranty agency’s ability to file suit, enforce judgments, initiate offsets, or other actions, to collect a defaulted student loan.”

It is impossible to discharge bad debts in this system under our normal mechanism for handling bad debts — bankruptcy. When delinquencies happen — say when you graduate into a recession that elites refuse to fix — you get thrown into the fee-churning world of private debt collection. This world was memorably described by law professor Ronald Mann as a “sweat box” of fees and other ways of increasing the total debt owed. With fees churning, there’s no date after which creditors can no longer go after your student loan payment, and they can even go after the baseline measure society has created to prevent poverty in old age.

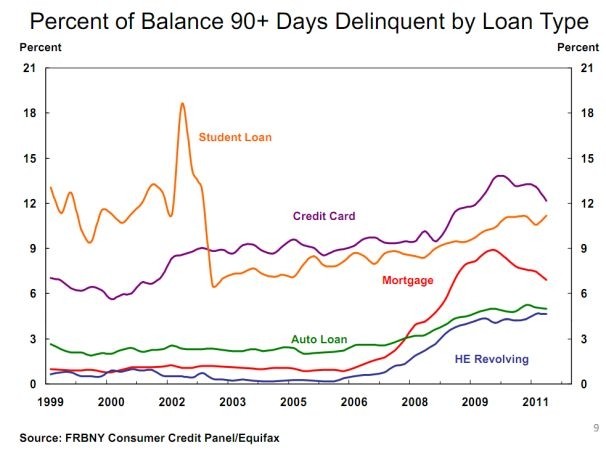

Now with all this in mind, let’s quickly examine the New York Fed’s recent release of its Quarterly Report on Consumer Credit, specifically this delinquency data:

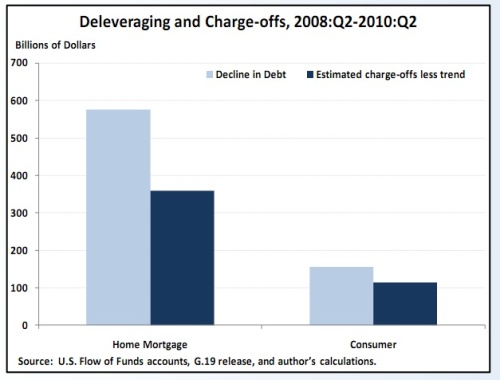

Student loan delinquencies look to be slowly increasing over time, while credit cards and mortgages go up and down. On the flip side of this dynamic is the amount of loans being “charged off” by private institutions. These are loans that will never be fully replayed, and a cost-benefit analysis tells the lender that it is no longer worth trying to collect the full amount. These are tough estimates to get, but Karen Dynan of the Brookings Institute has one estimate in her “Household Deleveraging and the Economic Recovery”:

As credit card and housing debt become unbearable, there’s a point at which they get written down. That point is too high, but because of various laws regarding debt collection that shift the strategy and potential end results between the actors, there’s a logic to it. As far as I can tell, there’s simply no equivalent chart, or even logic, for student loans. Because of legal choices we’ve made in how to set up this relationship, it stays forever, is virtually impossible to discharge under hardship, churns fees when it goes bad, and creditors can get to anything, including Social Security, to get it repaid. Meanwhile, we have a Great Depression-like event that is throwing college graduates into a labor market that is far too weak.

It is good to see President Obama, as part of his “We Can’t Wait” campaign, pushing to get some fencing around the rules for future student loan debtors through an executive order. According to this press release, the government will accelerate the implementation of laws “to limit loan payments to 10 percent of their discretionary income starting in 2012 [instead of 2014]. In addition, the debt would be forgiven after 20 years instead of 25, as current law allows.” However, according to an early analysis of this move, ”[b]orrowers with loans from 2007 and earlier will not be eligible. Likewise, borrowers who don’t have at least one loan from 2012 or later, like students who graduated in 2011 or earlier, also won’t be eligible. Borrowers who are already in repayment will not be eligible.” So the problem remains for now.

How is this not setting a generation up for complete disaster?

Mike Konczal is a Fellow at the Roosevelt Institute.