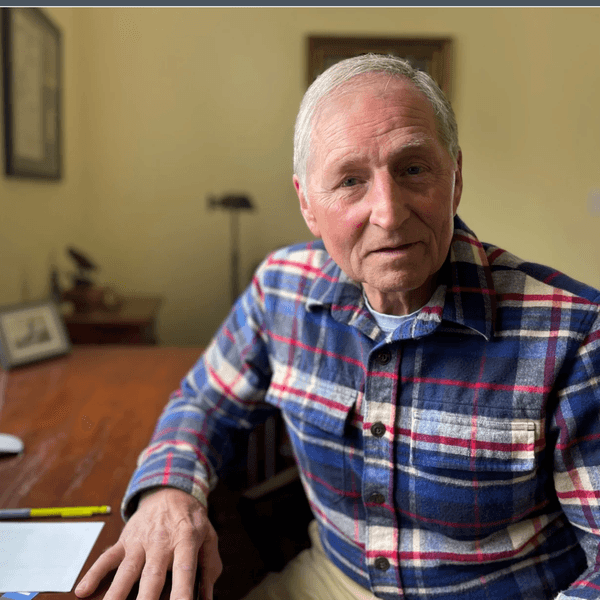

By Tim Grant, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

A competition among working homeless people to see who could save the greatest percentage of their pay provided researchers with valuable insights that could be used to encourage middle class people to improve their financial circumstance.

In what is believed to be the first detailed study of the savings behavior of the working homeless, assistant professor Sera Linardi of the University of Pittsburgh and colleague Tomomi Tanaka, an assistant professor at Arizona State University, tracked the savings rates of 123 residents in a Phoenix homeless shelter during a month in which they vied for a $100 prize for the biggest saver.

While the average savings rate increased by 33 percent during the competition, some people in the study group did not increase their savings rate at all.

Residents who already were focused on saving enough to leave the shelter were motivated to save even more, but those who were less inclined to save were not influenced by the competition.

“We found competition can make an object that is moving go faster, but it doesn’t make an object that is not moving move,” said Linardi, a behavioral economist at Pitt’s Graduate School of Public and International Affairs.

The research, published in the November 2013 issue of Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, omitted the name of the homeless shelter to avoid identifying any of the participants.

The homeless people in the study group had reached the highest status_Level 3 _ at the shelter. They had progressed from sleeping on a mattress (Level 1), to sleeping on a bunk bed (Level 2), to having their own cubicle (Level 3). They also had obtained work as cooks, janitors, telemarketers or commissioned sales people, and were on the verge of getting back on their feet.

“From the data that I have of 60 residents that actually completed an exit interview, they saved an average of $414 in 116 days total at the shelter, 45 days of which they were earning an income,” Linardi said, adding that the target savings is typically two months’ rent.

The amounts they saved varied. The top 25 percent of homeless residents saved $607. The top 10 percent saved $1,000 or more.

The average monthly income for those who had income was $450. The average income for all the shelter residents –including those with no income — was $240 a month.

Interestingly enough, when Linardi and Tanaka repeated the competition the following month, they no longer found any difference between the savings rate for the competition group and everyone else in the shelter. They speculate that was because the more aggressive savers in the first competition group had moved out.

They also suspect those who saved at a high rate the first month may have simply burned out, leading them to believe that while a savings competition can increase savings in the short run, the results diminish with repetition.

The competition may also have provided a glimpse into what motivates middle-class Americans to save.

“People want to be normal,” Linardi said. “The reason the competition was so successful in getting the homeless to save more is they don’t want to compete with people they already know have a stable footing, because everything in their lives is just so different. “When we put them in this competition, they feel, ‘Everyone here is like me; I can beat them.’ You level the playing field.”

That understanding might be helpful for inspiring others, as well.

“For one group of middle-class people, putting money into a 401(k) may be too far of a stretch,” she said. “They may simply want to pay their utility bill on time. So you group those people together and see if they can take one more step. For those who already have $100,000 in a 401(k), you group them and get them to take the next step from where they are. It’s about finding this perfect interval at which we can convincingly say, ‘You are all on the same level playing field.'”

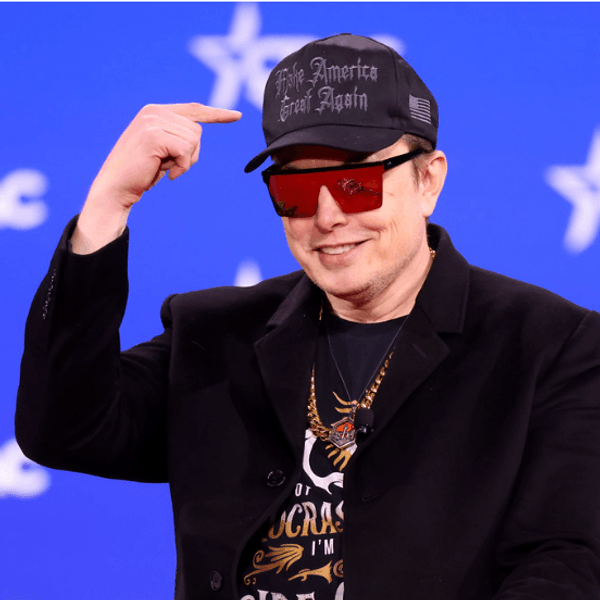

AFP Photo/Spencer Platt