By Jonel Aleccia, The Seattle Times (TNS)

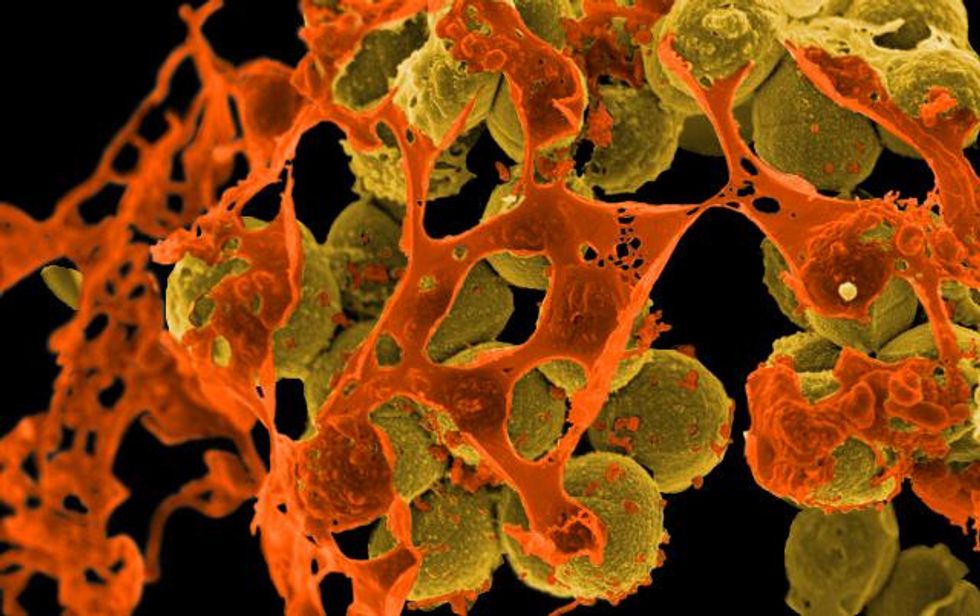

SEATTLE — An outbreak of drug-resistant “superbug” infections may have sent officials at Virginia Mason Medical Center scrambling for solutions, but hospitals across Seattle — and beyond — say they’re stepping up surveillance and safety practices, too.

No infections tied to contaminated medical scopes have been detected at Swedish Medical Center, but Dr. John Pauk, the hospital’s medical director of infection control, is taking no chances.

Last month, Swedish started performing daily cultures on the specialized endoscopes used for the procedure identified in the Virginia Mason outbreak, plus at least seven other similar outbreaks nationwide.

“Luckily, so far, we haven’t seen anything,” said Pauk. “But I don’t think any hospital system could fairly say there isn’t a potential problem with their scopes.”

They’re testing for multidrug-resistant bacteria that could stick to the devices, even after recommended cleaning, and spread from one patient to another, potentially causing dangerous infections, Pauk said. The Virginia Mason outbreak infected 32 people, including 11 who died, though it’s not clear whether the superbug played a role.

Officials at Harborview Medical Center, the University of Washington Medical Center, Providence Everett and the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System say they’ve also recently begun testing the scopes.

“It’s kind of been on people’s radar screens, but the scope of the problem was not totally understood,” Pauk said.

Then came recent reports of the superbug in Seattle, Los Angeles and Hartford, Conn., in addition to previous outbreaks in Pennsylvania, Illinois and Florida. Those have echoed reports dating to the early 1980s of potential cross-contamination spread by the scopes.

The trouble, critics say, is the design of the devices, known as duodenoscopes, used for ERCP, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, a procedure that snakes a scope down the throat and into the gut to diagnose and treat problems with the pancreatic and biliary ducts. A channel on the end of the scope that is used to hold and move tools has intricate crevices that can trap bacteria.

The scope is different from those used to perform colonoscopies, hospital officials emphasize.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned last month that transmission of infections may occur even after meticulous cleaning of devices. In the U.S., the scopes are made by three manufacturers: Olympus America, Pentax Medical and Fujinon, though Olympus has the largest market share. But the agency has not called for a recall or redesign of the devices.

Swedish performs about 1,000 ERCP procedures a year, placing it second in local volume only to Virginia Mason, which logs about 1,800 procedures annually. UW Medical Center performs about 500 ERCPs each year, Providence Everett performs about 250 and Harborview about 200. VA Puget Sound performed 89 procedures in Seattle in 2014.

Nationwide, more than 500,000 people undergo ERCPs each year. The procedure can be lifesaving, which has made FDA officials reluctant to pull devices from the market, they said.

Pauk said Swedish officials took their cue from Virginia Mason, which launched a test-and-hold policy that quarantines the ERCP scopes until they’re free of dangerous bacteria. It’s a method recommended in a pending protocol being developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and in new guidelines just published by the ECRI Institute, a respected patient safety advocacy agency.

The most worrisome bug is CRE, or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, a family of germs resistant to nearly all top-gun antibiotics available to treat them. They can cause infections with a mortality rate as high as 50 percent.

“The reality is, as we look at this, more and more hospitals are going to encounter this bug,” said Chris Lavanchy, engineering director in the health devices group at ECRI Institute.

But Virginia Mason’s outbreak was caused by different kinds of multidrug-resistant bacteria, including hyper-AmpC-producing E. coli. And an outbreak at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut was caused by a strain of ESBL, or extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, E. coli.

From a patient’s standpoint, the new surveillance in Seattle and elsewhere is good news, said Lawrence Muscarella, a patient safety expert who has been tracking infections tied to dirty endoscopes for years.

Before they agree to ERCP procedures, patients should ask several specific questions, he said.

“You can ask: Did you have any CRE or related superbug infections within the last two years? Were any linked to endoscopes? What are you doing to ensure my safety?” Muscarella said, adding:

“Before, patients never knew what questions to ask, so hospitals never had to answer.”

(c)2015 The Seattle Times, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Image via NIAID