Before getting to the encouraging news for Democrats, I want to stipulate a couple of things:

First, while it’s too early to know the full political impact of the violent attack on Paul Pelosi, the vicious MAGA conspiracy-mongering that was present in the assailant’s social media account is certain to change the national conversation in the ten days before the midterm elections. The depressing incident — a reflection of the dramatic increase in violent threats against members of Congress and other officials since Donald Trump’s election — will likely generate pressure on Republicans to denounce the violence on January 6 and explain their blind allegiance to Trump, who has retweeted dangerous QAnon lies for years. And it may highlight Nancy Pelosi’s reminder that “democracy is on the ballot” this fall. But right now, we have no idea if any of this will affect the outcome.

Second, even accounting for the Worrywart Gap — macho Republicans are always more confident about their chances than Debbie Downer Democrats (who use fears of losing to raise money in annoying emails) — holding the House seems increasingly out of reach for Democrats. The only question is whether it’s a blowout or closer-than-expected. The latter — which I anticipate — would put Democrats in a good position to regain control in 2024, after two years of the antics of Jim Jordan, Marjorie Taylor Greene, and the other creeps and fools who will be in charge of the House.

Why do I think we’ll see a mixed bag on November 8 instead of the full fruitcake? The short answer: Bad GOP Senate candidates, unreliable polls, and a stupid GOP turnout strategy.

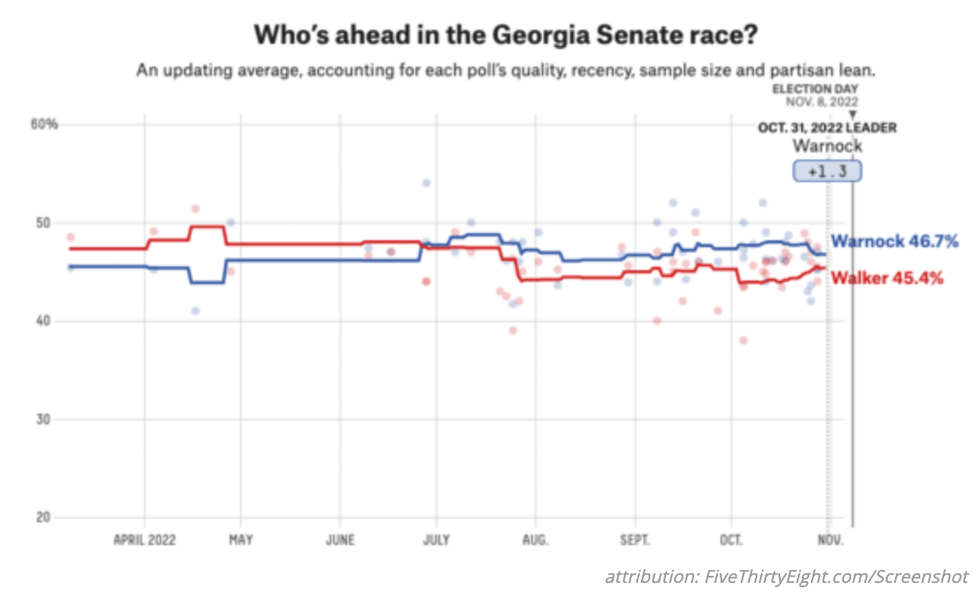

I’m betting on Mark Kelly to beat Blake Masters in Arizona and Raphael Warnock to prevail over Herschel Walker in Georgia. Catherine Cortez Masto could go down in Nevada because her opponent, Adam Laxalt, isn’t crazy, though early voting there looks decent for Democrats. If one of those Democrats loses, holding the Senate would require John Fetterman and/or Tim Ryan flipping seats in Pennsylvania and/or Ohio, and I think at least one of them will. I’m not sure Mandela Barnes is going to make it, but don’t underestimate the Wisconsin Democratic Party’s legendary ability to turn out the vote. Cheri Beasley is within striking distance in North Carolina and Mike Franken has a bit of momentum against 89-year old Senator Chuck Grassley in Iowa. Utah is a wild card, with challenger Evan McMullin uniting independents and Democrats against Senator Mike Lee. To recap in a way I haven’t seen in the press, Democrats are having trouble defending seats in Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada, while Republicans are having trouble doing so in Iowa, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Utah. Sounds to me like a recipe for continued Democratic control of the Senate.

It’s hard to know for sure, but I’d argue that many polls are over-estimating Republican strength. Like any political junkie, I need my fix of Nate Silver and Real Clear Politics but these numbers we obsess over are nearly useless for any race where the results are within the margin of error. And the MOE is often twice what most people assume. As Pew Research, a reputable name in the survey industry, explains:

To determine whether or not the race is too close to call, we need to calculate a new margin of error for the difference between the two candidates’ levels of support. The size of this margin is generally about twice that of the margin for an individual candidate.

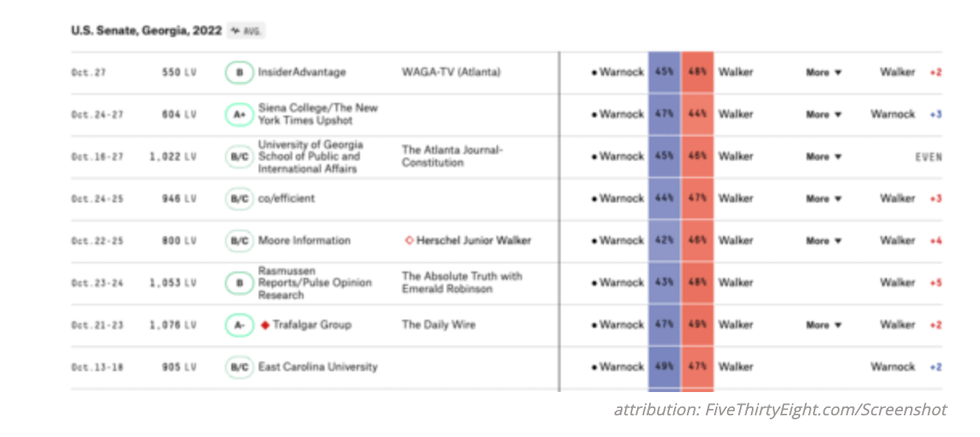

In other words, the true margin of error when you look at polls is not three or four points, but six or eight. Then there’s the dirty little secret of the polling business — that response rates are down from 36 percent at the turn-of-the-century to about six percent in 2020, which means that polls with fewer than 1000 respondents (the experts can argue over that number) are likely to be skewed.

It gets worse: Many “junk polls” with small samples or partisan connections are nonetheless included in the ubiquitous polling averages that so many readers rely on. Cycle after cycle, Rasmussen, for instance, over-estimates support for Republican candidates by as many as 10 points. But that poll remains in the Real Clear Politics average. Garbage in, garbage out.

Even venerable polls have problems. Polls sponsored by news organizations — like the New York Times/Siena College, Wall Street Journal/NBC News and ABC News/Washington Post — are at least partially branding exercises, where the incentive to promote the results can lead to hype. (I know, because for nearly 30 years I had a front-row seat on the Newsweek Poll, administered by the Gallup Organization, which was responsible for the infamous 1988 poll showing Michael Dukakis with a huge lead over George H.W. Bushafter the Democratic Convention).

Of course these polls are among those hiding their response rates, which may be even lower than six percent, given rightwing dislike for the mainstream media. But it’s not just press-haters who don’t answer or hang up. For its June survey, the NYTimes/Siena poll reported that 63 percent of respondents were reached on cell phones.

Who answers calls from unknown numbers on their cell phones? Nobody I know. Younger people don’t even talk on their phones to friends. (They text). That should give us some idea of just how low the response rates are on those calls.

And how about the 37 percent with landlines? Do you know anyone under 40 who still has one? My wife and I are in our sixties and even we recently got rid of ours. That helps explain why raw polls —before pseudo-scientific adjustments — often skew old and thus Republican. Not surprisingly, polls publicly disclose only an overall sample size, not the sample size of each cross-tab (sub group). This suggests that results from younger respondents are based on shockingly small samples.

Given the limitations of both landlines and cell phones, many pollsters are transitioning to online polls. Their claims of success with this relatively new method might be true, but I’m suspicious. By their very nature, participants in online surveys are self-selecting, and not weighted for demographics. When they think their results are unreliable, pollsters make a series complex adjustments to get a representative sample, adjusting for party affiliation and other factors that might help. Of course this “weighting” of polls is as much art as science — junk science.

And small shifts in the samples can render a poll meaningless. After the 2020 election, Pew did a study that showed that a shift of a mere 36 votes out of a survey of 1,000 shrunk Biden’s 12-point lead to the four points he actually won by.

Let’s look at how far off the final polls were in recent elections. They weren’t bad in the 2018 midterms, which Democrats — riding a wave of anti-Trump feeling — won by 8.4 percent, slightly better than predicted by the Real Clear Politics average (which was hampered by a Rasmussen survey showing the Republicans winning by a point). Democrats picked up 41 seats in the House but Republicans won two in the Senate, which suggests (not for the first time) that national trends aren’t especially relevant in Senate contests.

The 2020 presidential election was a disaster for the polling industry, which avoided intense scrutiny only because of all the attention paid to Trump trying to steal the election. The final Real Clear Politics averages had Biden winning by 7.2 percent; he won by 4.5 percent. Quinnipiac, a well-respected poll, had Biden up by 11 and NBC/Wall Street Journal had him winning by 10. Does that mean Republicans have a bigger lead now than it seems from the polls? Maybe, but it also could be that pollsters this year have overcompensated for their 2020 failures by weighting their surveys in favor of Republicans.

I feel sorry for the pollsters assigned to build “likely voter” turnout models. It’s complicated, of course, but I’d argue for an Occum’s Razor approach. The simplest and most telling data point is that overall turnout surged in the last two elections, and it wasn’t a coincidence that Democrats won them both comfortably. The key midterm statistic for me is that youth turnout (18 to 29-year-olds) went from 20 percent in 2014 (a bad year for Democrats) to 36 percent in 2018 — a 79 percent jump. Two years later, new voters (those who voted in 2018 but not in 2016) backed Biden over Trump by about two-to-one.

Which brings us to this year, when early voting is way up from the past. Simon Rosenberg of the New Democrat Network has been consistent — with me and others. No red wave, just a very close election. He thinks the early voting is looking good so far for Democrats:

But could it be that Republicans are just waiting for Election Day, when their anger over inflation and crime and President Biden will send them streaming to the polls? Maybe. In a Suffolk poll, inflation beats abortion by 16 points in the head-to-head matchup over which issue “matters more” in 2022—a disturbing finding for Democrats. Worse, about 60 percent of independents worry more about inflation.

But the Suffolk poll also shows that roughly half of women say abortion matters more, and neither this poll nor any other can truly measure how intensely these voters feel about it. The election could turn not on whether inflation or abortion is a bigger issue, but on which is a bigger motivator.

My sense is that while sporadic voters (the 50 to 60 million Americans who usually avoid midterms) are most concerned about inflation, more than a few may accurately (if cynically) conclude that no politicians in either party have any convincing plans to curb it — so they might as well follow their normal patterns and go to the gym or wherever instead of to the polls. By contrast, women voters most concerned about abortion know exactly where both parties stand and— if high turnout in this year’s special elections is any indication — will have a high likelihood of voting Democratic. My guess is that worries among younger men about their girlfriends getting pregnant could be an under-the-radar motivator. All it takes for Democrats to do well is for their numbers with younger voters to be close to those of 2018 than 2014.

Finally, I find it strange that there hasn’t been more commentary about the self-destructive GOP preference for Election Day voting. Tom Bonier, a Democratic consultant and CEO of TargetSmart, which does a great job tracking early voting, makes a good point about how Republicans will suffer because Trump made them abandon vote-by-mail, which is popular across the country for its convenience.

And that’s not even mentioning the weather. Everyone in politics knows that rain or snow dampens turnout. That maxim should now be revised to: Bad weather on Election Day hurts Republicans. Democrats can adopt the old line of Boston Braves fans about the great pitchers Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain:

“Spahn and Sain and pray for rain.”

Jonathan Alter is a bestselling author, Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker, and a contributing correspondent and political analyst for NBC News and MSNBC. His Substack newsletter is OLD GOATS: Ruminating with Friends.

Reprinted with permission from OLD GOATS