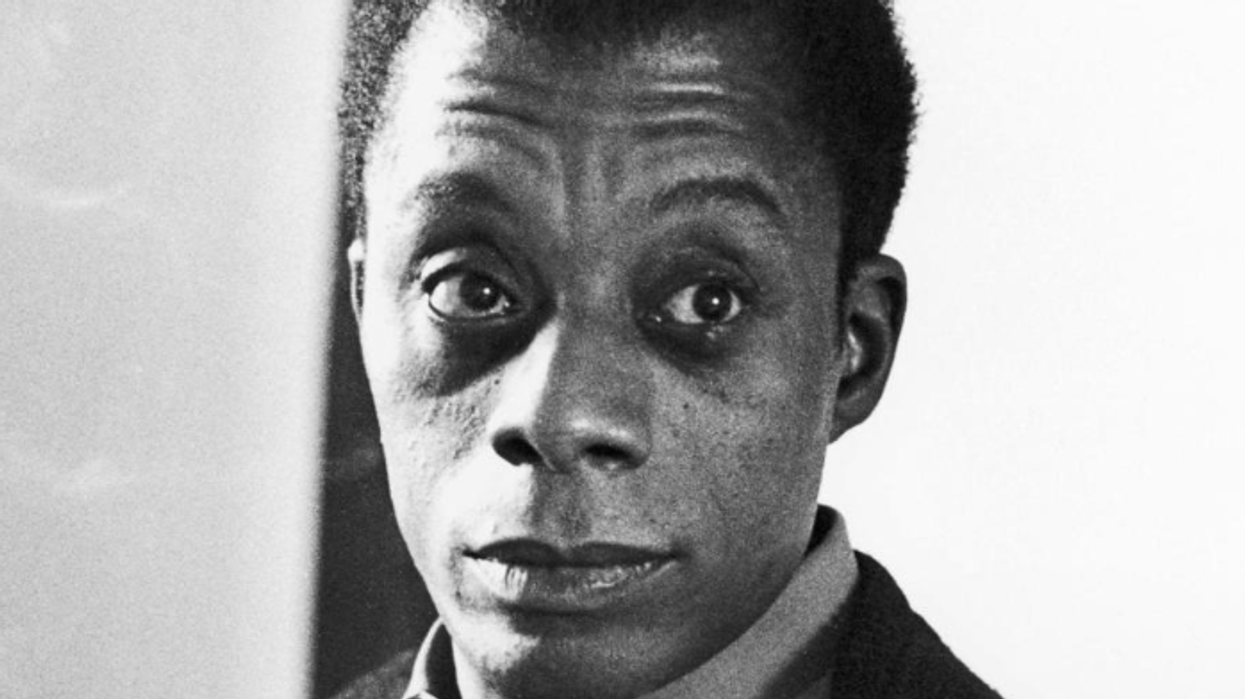

Centennial Of A Prophet: James Baldwin's 100th Anniversary

You're born poor in Harlem, the oldest son, and hit the streets in the Depression doing errands and odd jobs. Your father gives you a dime to get kerosene. You fall on the ice, losing the dime. Your father beats you. He says you're ugly.

Your mother is your salvation. You help her with baby after baby. Your father works in a factory and as a church minister on Sunday. You're a preacher's son and preach to young people.

You love when the church rocks and sings the power and glory. You're not religious, but knowing the Bible shapes your sonorous voice for the ages.

A school principal sends you to the public library. A cop says, "Why don't you stay uptown where you belong?"

You grow up fast, a complex soul, and move to Greenwich Village. You work as a waiter and at an army depot.

You're an outsider on two counts: Black and gay. The 1950s were so rigid, you need to breathe freer air.

So you sail to Paris, once your first novel is out: the autobiographical Go Tell It On the Mountain. At 29, your life becomes a tale of two cities, New York and Paris, with friends on both shores.

But you are always American. Maybe you see your country more clearly from over the ocean. We see it more clearly thanks to you.

Your name is James Baldwin, the major 20th-century author. You were born in 1924. This is your centennial year.

Gone for years, Baldwin stays ahead of our time as a literary prophet.

A Northerner who felt the Southern sting of Jim Crow law, Baldwin foretold the racial fury and protests that spilled onto streets when George Floyd was choked by police in 2020.

Baldwin's powerful essays and novels are his main legacy.

For the novels alone, he belongs in the pantheon. "Giovanni's Room" is a self-portrait in Paris and tells of a tragic gay love. His publisher turned it down.

Baldwin's wrenching fiction paints a lynching at a village picnic; police brutality ending in suicide; a white farm boy getting his neck broken.

In the lynching story, Baldwin forces us to face the fate of thousands of African American men.

A blunt declaration underlies Baldwin's work: "The American Negro has the great advantage of having never believed that collection of myths to which white Americans cling."

Baldwin's characters are Black and white. Race lies at the heart of his work. Following footsteps of the Harlem Renaissance writers, he surpassed almost all.

Baldwin's social criticism cuts to the bone. His rise as a writer accompanied the Civil Rights Movement.

The movement became the music to his words. Baldwin knew Martin Luther King Jr. and attended the 1963 March on Washington. He visited Selma, Montgomery, Atlanta, the places that made bloody history. Baldwin lived civil rights on the front lines.

Once Baldwin brought freedom riders to confront Attorney General Bobby Kennedy. Harry Belafonte and others demanded the Justice Department protect peaceful marchers. Kennedy was shocked at the barrage.

1963 was an inflection point, sun shadowed by a Klan church bombing that killed four girls in Alabama. Then came the November knell: President John F. Kennedy's death drove the nation into despair.

The year before, a sweeter note with the Kennedys had sounded. Baldwin was a guest at the famous White House dinner for Nobel laureates. That year he turned 38 and published Another Country.

Authors William Styron and Norman Mailer and actor Marlon Brando were among his friends.

For all Baldwin's slings and arrows, he lived in the light of genius. No starving writer, he became a posh citizen of the world seen in Istanbul and Paris cafes. He called others "baby.'

Baldwin had a home in France. Yet he was never at rest.

The classic novel, If Beale Street Could Talk, arose from Baldwin's bleak vision at 50.

His great love was a Swiss man, Lucien Happersberger, who had a cottage in the Alps. They spent a winter there when they were young — a long way from Harlem.

Baldwin became Lucien's son's godfather.

As Baldwin lay dying in France, Lucien and his brother David stayed by the writer's side. James Baldwin was 63.

The author may be reached at JamieStiehm.com To find out more about Jamie Stiehm and other Creators Syndicate columnists and cartoonists, please visit Creators.com.