This is the fifth column in a nine-part series about Melissa Lucio and the State of Texas’ capital case against her. Read the first column here, the second here, the third here, the fourth here, the sixth here, the seventh here, the eighth here, and the final column here.

It’s impossible that the twelve jurors who decided death row inmate Melissa Lucio’s guilt and punishment weren’t affected by the prosecutor’s evidentiary sleight of hand: knowingly admitting a false disciplinary record for Lucio into the trial record.

Attorneys for Lucio have interviewed former jurors and report that none of them mentioned the discipline record as influencing their decision. Then again, no one asked them, either.

But the jurors might not prove the most reliable sources on what guided their votes. For one, those days of deliberation hang more than thirteen years behind the frenzy to save Lucio’s life; it’s hard to remember. Secondly, the jury charge — the court’s instructions to jurors on how they should arrive at a decision — directed them to settle the issue of whether there is “a probability that Lucio would commit criminal acts of violence in the future.” Unanimously, the twelve of them voted that there was a probability — but they’re taking that back now.

Juror Johnny Galvan, Jr., opined in the Houston Chronicle on April 3 that he wouldn’t have convicted and sentenced Lucio to death. He made a similar statement at a hearing before the Texas legislature on April 12, 2022 when he said other jurors pressured him into the vote.

Identifiable jurors refused to reply to interview requests, except for one juror, Erminio Cruz, who answered my text with “don’t bother me.” Cruz’s post-trial declaration, dated March 5, 2022, includes statements like “I still agree with my decision to give death (sic) because we had enough evidence”, “Nothing the defense presented could have made me not give the death penalty”, “I don’t remember most of what we discussed” and “I think everytime someone is found guilty of murder they should be hung.”

The statements seem contradictory. But the addendum to Cruz’s declaration might be the most trustworthy. It states. “I remember someone saying during deliberation on penalty that if we didn’t decide now we’d be there all day.” Neither justice nor retribution motivated the jurors on July 10, 2008; it was convenience. Theirs, not Lucio’s.

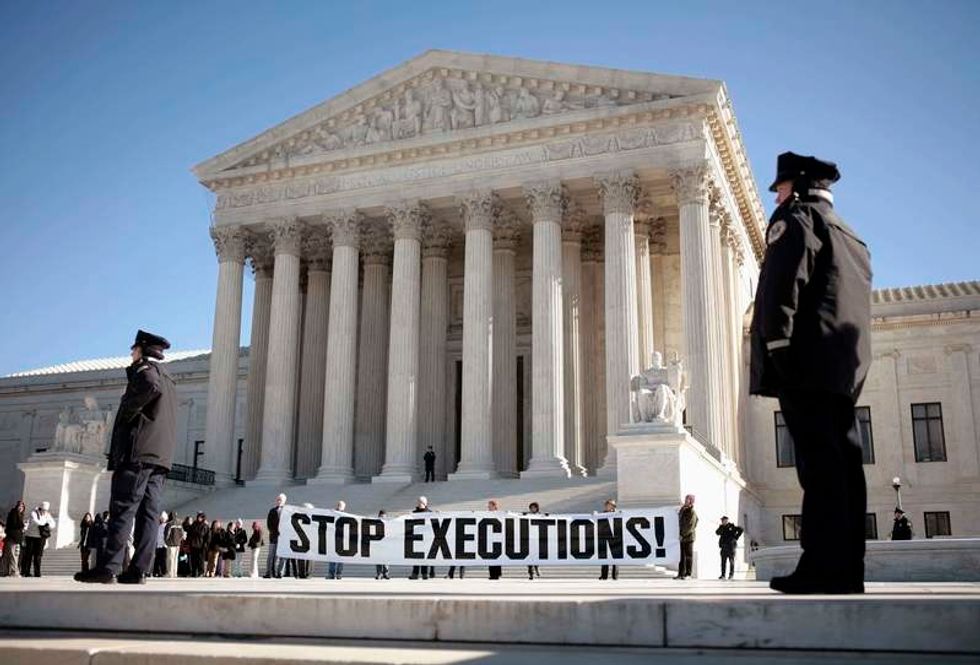

Race cannot go without mention in any discussion of capital punishment. The death penalty finds victims in minority populations. About 43 percent of total executions since 1976 and 55 percent of those currently awaiting execution are racial minorities.

Lucio’s race may or may have been a factor for her jury without their knowing it; most times when the race of a defendant influences a jury verdict on death it’s the result of implicit bias, a prejudiced worldview that’s much more pronounced in death-qualified jurors (those who state that they can and would impose death as a sanction if they thought the law and the facts supported it).

Women accused of capital crimes are understudied and bias in deliberations becomes a multi-factorial analysis; the role of gender complicates racial prejudice.

Juries impose the death penalty on women much less frequently than they do men. To wit, 18 women have been executed in the United States since 1976, compared to 1345 men. And the racial composition of that group of 18 women isn’t disproportionately minority. Thirteen women or 72 percent who perished at the hands of the government were white. Four were Black and one was Native American; there’s no record of a Latina woman undergoing capital punishment since it was deemed constitutional again in 1976 after a four-year hiatus brought on by the Supreme Court’s opinion in the case of Furman v. Georgia.

While a death sentence can hardly be described as unique in Texas – the state with the most executions since 1976 – Lucio’s case blazes a trail in that she was the first Latina sentenced in this way in the South. Other Hispanic women sentenced to death have come from the western region of the country. The South is known for sentencing women to capital punishment but not Latina women.

Lucio would be the only Latina on death row outside California, a singularity that made allegations of misconduct easier for a jury to accept.

Even if asked how Lucio’s jail file affected their decision making that day, juror input on the effect of the illegal jail file wouldn’t help much, although the record indicates that they held these pernicious papers in their hands.

Questioning Lucio’s jurors to review their decision is a waste of time, according to Robert Swafford, JD, founder and owner of the Austin, Texas-based Strike for Cause Jury Consultants. The human ego works hard to justify previously made decisions. “If they were to say… ‘Oh if I had known this, I would have made a different decision’ that would mean that they've done something bad. It would affect their idea of themselves as a human being.”

Capital punishment experts as well as jury experts agree that the file probably filtered into juror consciences. Robert P. Johnson, Professor of Justice, Law and Society at American University and author of Condemned to Die: Life Under Sentence of Death and Death Work: A Study of the Modern Execution Process and expert witness in capital cases [disclosure: Johnson is the editor at Bleakhouse Publishing which published my book of poetry] said of including the disciplinary file: “It would likely have an impact.” [Disclosure: Johnson is the editor at Bleakhouse Publishing, which published my book of poetry.]

Brian Bornstein, professor in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University, hasn’t worked on the Lucio case. But he wrote in an email that, assuming that the records were introduced as alleged proof of dangerousness: “it seems quite likely that it would influence jurors’ decisions to sentence her to death, as dangerousness is a key factor in sentencing, especially under Texas’ capital sentencing guidelines.”

Bornstein’s research on juror decision making bears mention here. Lucio’s guilty verdict — rendered just two days before the death sentence and one day before the unexpected witness, Cameron County Jail Disciplinary Officer Carloz Borrego appeared with the file — provided the lens on what punishment she received.

“[J]urors tend to seek out and remember information that is consistent with their verdict preference and scrutinize and reject information that is inconsistent with that preference” Bornstein wrote in a 2011 article in a journal called Current Directions in Psychological Science. By the time they bickered over punishment, these jurors no longer had a predilection for guilt; they had perfected it just days earlier.

Even if the jurors would have landed the same way today as they did on the day of Lucio’s condemnation, that doesn’t mean that the judgment shouldn’t be cracked open like a hollow Easter egg.

The legal aphorism that one can’t “unring a bell” first appeared in American jurisprudence in a 1912 case in the Oregon Supreme Court, where the victim of an alleged arson testified about the defendant’s motive; namely, he was retaliating against the victim for reporting him for “tail-cutting” — slicing the tail off a cow. Without evidence of this specialized butchery, that testimony prejudiced the defendant with the jurors. “It is not an easy task to unring a bell, nor to remove from the mind an impression once firmly imprinted there,” the judges agreed.

The unrung bell appeared again in a case before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, the federal circuit that includes Texas, in 1962. “It is better to follow the rules than to try to undo what has been done. Otherwise stated, one "cannot unring a bell"; "after the thrust of the saber it is difficult to say forget the wound"; and finally, "if you throw a skunk into the jury box, you can't instruct the jury not to smell it."

Lawyers and judges talk about unringing bells to emphasize that if the prejudicial effect of a piece of evidence outweighs its probative value, the evidence should be excluded or any result drawn from it should be reversed. It’s fancy language but it’s not clear it would even apply in Lucio’s case. Lucio’s file was false. It had zero probative value. It was all prejudice.

Reversing Lucio’s judgment of death should be easy for any court regardless of the jurors’ positions, even though, according to Texas case law, it can consider a defense attorney’s failure to object to inadmissible evidence like this perfidious file as a valid trial strategy. That’s an outrage in itself.

But neither of Lucio’s lawyers ever justified it that way. They didn’t have to. Up until now, no one ever realized the file that undoubtedly colored jurors’ perceptions was a lethal falsehood.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.