You, the readers, support this work I do with your paid subscriptions. If you haven’t yet subscribed, please pitch in and help. It will be much appreciated.

I want to tell you a story about Black History. I sublet Jack Whitten’s loft on Broome Street in Soho during the summer of 1969. I knew he was an artist, but when I first climbed the stairs and walked into his loft, I didn’t know what to expect. The door opened into his painting and sculpture studio at the front of the loft where four big windows poured light down on the paint-stained floor. The first thing I saw was a big piece of wood carved roughly from a tree trunk sitting in the middle of the floor. It was thick and dark-colored and must have been four or five feet long and three feet high, and into it, Jack had driven what looked like a thousand four-inch nails. Works of art are said by many artists to speak for themselves. Although I did not see it in this way at the time, that piece of art spoke in the unmistakable voice of Black History. It spoke of violence, but it was not about the violence of hammering nails into the wood. Jack Whitten’s sculpture told the story of having the nails hammered into him.

What happens to you when you confront a great work of art? Well, it changes you. Great art speaks to you. It teaches you. It tells you what it means.

Listen to Muddy Waters sing “I got my Mojo Working,” or Slim Harpo sing “I’m a King Bee,” or Howlin’ Wolf sing “Meet me in the Bottom.” You are listening to Black History. Listen to the right hand of Thelonious Monk picking out the discordant notes and off-chords of “Round Midnight,” or stand before Alison Saar’s life-size sculpture of a Black woman in a long dress on a plaza in Harlem and witness the power of Black History.

I was thinking last week that maybe I should write something for Black History Month, because during the last year Black History has constantly been in the news, and not in a good way. Black History has been turned into a political issue by racists who are afraid of it. Ron DeSantis in Florida and Republican legislatures around the country are attempting to censor the teaching of Black History. They want to erase the history of slavery and the oppression of Black people under Jim Crow and the struggles of the Civil Rights movement. They want to deny the contributions made by slaves, Black human beings who were not even recognized as citizens, and yet who toiled to build dams and roads and bridges and even the same U.S. Capitol building that racist insurrectionists assaulted two years ago. I thought maybe I would write about DeSantis and Republican fear of Black History and what he and the others are trying to do to erase it when this popped up in my news feed:

Stax Volt Tour 1967 feat. Otis Redding, Booker T. & The MGs, Sam & Daveyoutu.be

It’s from a film that was made of the Stax-Volt tour in 1967 that featured Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Booker T and the MG’s. You don’t have to watch the whole thing, although it’s worth taking the time, because it’s as good an example as there is of what DeSantis and his ilk afraid of. It’s 25 minutes of the power of Black culture – in this case soul music from the 60’s – but it could just as well be a Beyonce video, or concert footage of Kendrick Lamar, or Steve Lacy, or Lizzo, or Sister Rosetta Tharp, or Sly and the Family Stone, or Jimi Hendrix, or Muddy Waters, or Howlin’ Wolf, or Slim Harpo, or Marvin Gaye, or Ike and Tina Turner.

I could sit here all day long listing Black performers and never reach the end of what they have given us, how much they have added to the history of the United States of America. So much of what we know of the Black experience is from musicians like Thelonious Monk and Aretha Franklin and from writers like James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates and Langston Hughes, and from painters and sculptors like Jack Whitten and Vivian Browne and Kara Walker.

There is a song on the Stax-Volt video by Otis Redding called Try a Little Tenderness. It’s one of his greatest songs. It tells the story of two struggling people and how they cope with what life has dealt them.

Oh, she may be weary

Them young girls they do get weary

Wearing that same old shabby dress, yeah, yeah

But when she gets weary

Try a little tenderness, yeah, yeah

You know she's waiting

Just anticipating

The thing that you'll never, never, never, never possess, yeah, yeah

But while she's there waiting

Without them try a little tenderness

That's all you got to do

It's not just sentimental no, no, no

She has her grief and care, yeah, yeah, yeah

But the soft words they are spoke so gentle, yeah

It makes it easier, easier to bear, yeah

You won't regret it no, no

Young girls they don't forget it

Love is their whole happiness, yeah, yeah, yeah

The song itself is a piece of Black History because it’s Otis Redding and the story he is telling is coming from such a deep place within him. How much more can you tell someone about the common pain we all share as we live our lives? The power of Otis Redding’s song is right there in in front of us. He’s giving us the whole of his life and what he knows about living it. It’s everything he has.

And then look at the young people in the audience. They don’t have to listen to every lyric to know the truth of what he’s telling them. It’s right there in a single word, “tenderness,” and it’s in his voice. It washes them like babies in a sink. You can see its power in their faces.

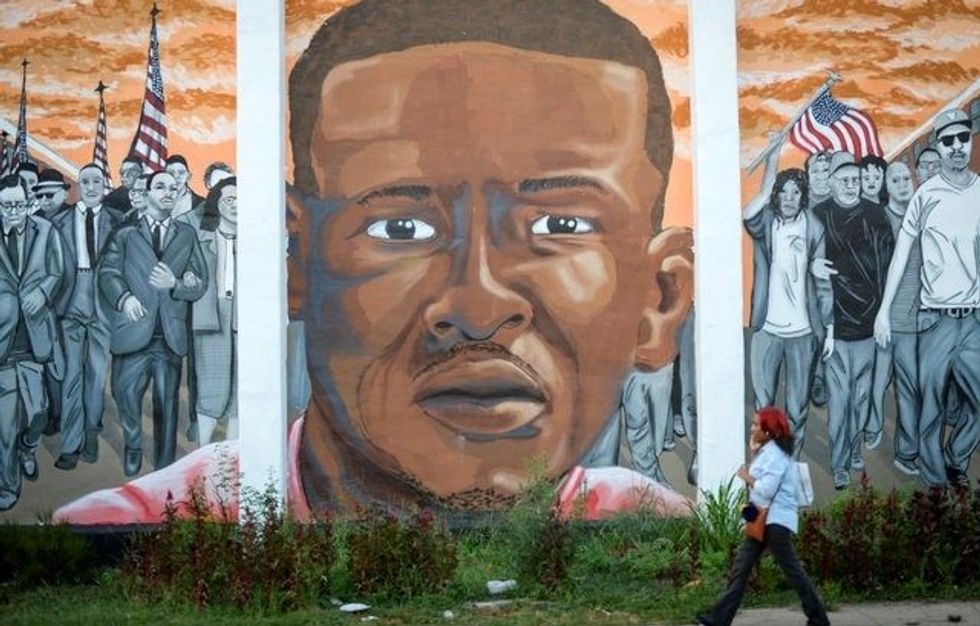

That is what racists are so afraid of. They are afraid of the power that comes from having been Black in America and survived. Black History, as it is taught in schools and universities, tells the story of how Black Americans have survived oppression, and it is accessible by switching on your television or hitting a button on Spotify or watching the Grammy’s or walking down a street in New York City and looking at a sculpture, or going into a museum and standing before a painting. Black History and the truth of Black experience is right there in the culture, in fact it dominates the culture all of us live in. Racists can’t avoid it, nor can their children or wives or friends or brothers or sisters. They try to censor it and deny it and build walls around it because they are so frightened of its power.

Black culture is American culture. It is so politically powerful, we exported it to counter Soviet Cold War propaganda during the Cold War. In the mid 1950’s the State Department sent the Dizzy Gillespie band, with Quincy Jones as its musical director, on a 10-week tour around the world, through the Middle East, Asia, and South America. Crowds clamored to hear them everywhere. On YouTube, you can see film of tours over the years by jazz and blues and rhythm and blues greats through Europe, playing Paris and London and Brussels and Oslo and Stockholm and Madrid. With today’s Black music and culture, from contemporary jazz to hip hop, as they say, fuhgeddaboudit. It has taken over the world.

Rappers tell Black History in Atlanta and New Orleans and South L.A. and the Bronx and Brooklyn. It was on the Grammy’s last night when Beyonce received her 32nd Grammy award, when Steve Lacy sang Bad Habit, when Stevie Wonder paid tribute to Motown with Smokey Robinson singing his hit, The Way You Do the Things You Do, when Stevie joined country music singer and songwriter Chris Stapleton singing his hit, Higher Ground.

I grew up listening to these giants of Black music. One night at the midnight show at the Apollo Theater on 125th Street, I saw, on a single bill, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Solomon Burke, the Temptations, and Joe Tex. Seats in the first balcony cost $1.75. Elsewhere, in small clubs in New York City, I saw Muddy Waters, I saw Jimmy Rushing, I saw John Lee Hooker, I saw Etta James, and I’ve written here about seeing Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot and Slim Harpo at Steve Paul’s Scene. No matter what was charged at the door of those clubs, even if it was a fortune, it could never cover the debt we owe these giants who opened up their lives to us.

It was Black History. All of it. That was what was behind the music and the art and the books – history, personal and cultural and political – history as it was lived by every one of those artists and musicians and writers. Can you imagine opening up and letting others into your lives like that?

Racism and Black History cannot coexist. That is why Republicans like DeSantis are trying to censor it. But they’re fighting a losing battle, because Black History is all around us, shared by Black artists and writers and musicians. It is a powerful truth that no politician, no racist policy, no discriminatory practice, no ignorant rhetoric, no Supreme Court decision, no hateful speech can ever erase. Up against the richness and power of art and music and literature that is Black History, racists lose.

All there is to do, this Black History month and every Black History month, is to give thanks. Have a look at that 1967 film of Otis Redding and Sam and Dave and Booker T and the MG’s and tell me that’s hard to do.

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist, and screenwriter. He has covered Watergate, the Stonewall riots, and wars in Lebanon, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels. You can subscribe to his daily columns at luciantruscott.substack.com and follow him on Twitter @LucianKTruscott and on Facebook at Lucian K. Truscott IV.

Please consider subscribing to Lucian Truscott Newsletter, from which this is reprinted with permission.

Trump Cabinet Nominee Withdraws Over (Sane) January 6 Comments