Yellowhammer File 3: How Alabama Is Murdering Prisoners By Medical Neglect

“45 y/o {African-American Male] with [left] shoulder pain 9/2022, finally obtained above path report today” was the note Wilcotte C. Rahming, MD made in inmate Antonio “Tony” Smith’s chart at Kirby Correctional Facility in Mt. Meigs, Alabama outside of Montgomery.

The date of the note was March 16, 2023, approximately six months after Smith alerted medical practitioners that something was wrong, that he was experiencing pain in his arm and shoulders. Doctors found later that Smith has non-small-cell lung cancer. On May 24, 2023, Smith’s medical chart included this update on his malignancy: “Advanced, recurrent or metastatic.”

“I had been complaining about my shoulders and my arms a long time ago. It took them almost seven months to start my treatment,” Smith said. Still, his medical records are replete with recommendations from outside providers and slim on actions by doctors within the prison system.

The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) insists that Smith receive only chemotherapy that is very debilitating instead of the radiation recommended by Daniel Sufficool, MD, a radiation oncologist with Alabama Cancer Care, a treatment center that isn’t affiliated with the Department of Corrections but examined Smith earlier this year. The chemotherapy-only protocol has left Smith in pain, unable to sleep and treated with opioids that cause significant gastrointestinal distress. It’s also not working, Smith learned on June 27.

Right now, the ADOC won’t even consider releasing him so he can receive the fully ordered course of treatment. ADOC Commissioner John Q. Hamm admitted as much — on the same day Smith found out that his current treatment was failing — at the Alabama Legislature’s Joint Committee on Prison Oversight’s hearing: “That individual is terminally ill…He was still very capable of committing crime.”

Hamm forgets that anyone is capable of committing a crime and that ADOC itself had certified him as low risk. Hamm’s department sent Smith to Red Eagle Community Work Center, sometimes known as an Honor Camp, where he was allowed to work in the community because his behavior record is exemplary. He’s at Kilby Correctional Facility now solely for medical treatment. Smith lost freedom simply because he is ill.

Smith is caught at the crossroads of two policies that inflict unique harm on people caught in Alabama’s criminal legal system: first, the renewed reliance on what is essentially the same healthcare company that has been found liable in a number of prisoner deaths in other states and second, illegal changes to the Board of Pardons and Paroles.

If Hollywood writers were working right now, they’d say the narrative of health care and supervised release was over the top for the average audience. Yet, in Alabama, it’s reality.

Last year, the ADOC announced a 1.2 billion contract with YesCare, which was formerly known as Corizon Health, and then abruptly and inexplicably withdrew from it. The state legislature paused the closing on the contract until they were satisfied YesCare’s bid — far from the lowest offered — wasn’t influenced by inside actors, namely a a now-former member of YesCare’s Board of Advisors who is also the lead attorney defending the ADOC in civil actions that include claims of deliberate indifference.

At one time, this attorney, William (Bill) Lunsford, now a partner at the firm Butler Snow, had one fiduciary duty to YesCare and another continuing duty to make sure that the ADOC not be held liable for contracting with them. The two obligations are incompatible with healthy inmates. Lunsford is denial of care personified.

How Lunsford procured this power is another almost-too-nuts-to-believe tale. Last spring, Attorney General Steve Marshall stripped all the ADOC’s in-house counsel of their Deputy Attorney General designations thus precluding them from representing the department in litigation. That means that all defense litigation, including the overwhelming task of defending the ADOC in a lawsuit filed in 2020 by the Department of Justice under the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act or CRIPA, lands in Lunsford’s lap, along with any claims against YesCare, a company he once advised.

YesCare is just a rebrand of the same company that the state dumped years ago because its care was so deficient that it mired the ADOC and its cast off company, Corizon, in litigation. YesCare is known to ignore patients who might have cancer.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program (ADAP) issued a report in June 2014 titled “Cruel Confinement: Abuse, Discrimination and Death Within Alabama's Prisons”; within the two organizations concluded that “[n]umerous prisoners have complained of symptoms for months without anyone addressing their concerns, only to be diagnosed with advanced stage cancer that is terminal by the time it is diagnosed.”

The SPLC and ADAP filed a class action suit against the Alabama corrections department, including claims that prisoners’ mental health needs were so severely neglected that it violated their constitutional and civil rights. This suit culminated in a court order issued by United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama Judge Myron H. Thompson in 2017 to bring care up to standards that don’t violate the Eighth Amendment. The litigation continues to this day — June 2023 — to get ADOC to comply.

To be clear, not all blame can be laid at YesCare/Corizon’s feet. Neither Corizon nor YesCare has provided care since 2018; Wexford Health Sources Inc. took over back then — and earned $842,339,355 in approximately five years — and were in place for Smith’s delayed diagnosis.

But the staff remained the same and that’s a problem, too. According to a nurse who worked alongside Dr. Rahming at Kilby Correctional Facility while Wexford Health provided care, (we are withholding her name) even the medical charts aren’t accurate.

“Whatever Dr. Rahming said for them to put down on the paper... That's what they put down. They don't put down the actual findings or actual facts when they know that something is wrong” she said in an interview.

Wexford Health’s interregnum between Corizon/YesCare’s oppressive reign shows that it’s the contract enforcement that is the problem in Alabama and that duty belongs exclusively to the executive branch of state government.

Other men incarcerated in Alabama have either developed cancer or watched pre-existing diagnoses decimate their bodies as they go untreated.

His demands for prostate-specific antigen testing failed for years and now 65 year-old Billy Mitchell, confined at St. Clair Correctional Facility in Springville, just received a diagnosis of prostate cancer that uprooted him from the lower-security Childersburg Work Release Center.

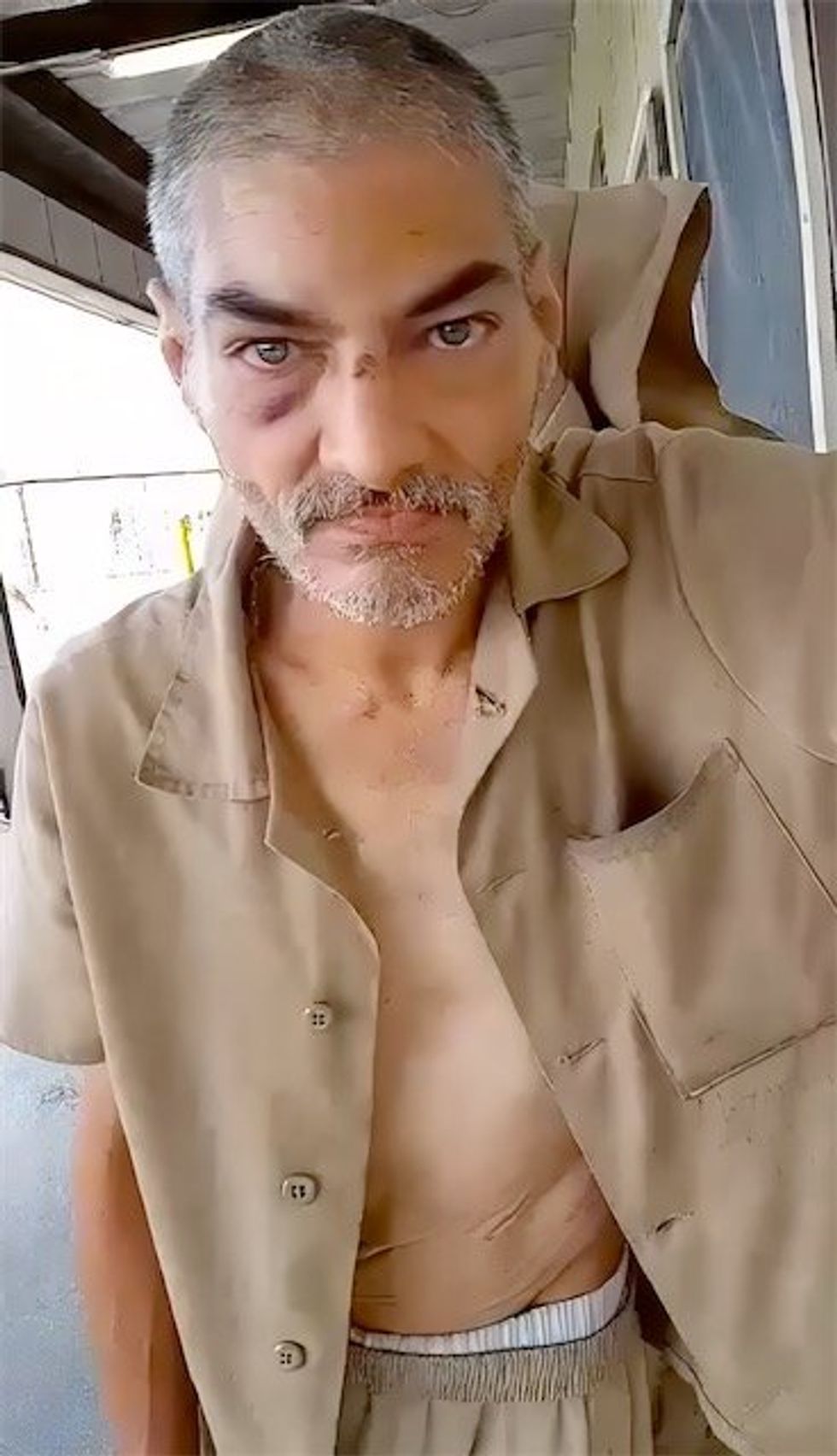

Another, Allen Jacob Hebert, incarcerated at Ventress Correctional Facility in Clayton, Alabama, says he was diagnosed about four years ago with Stage 2 “thoracic lymphatic” cancer. Given recent extreme weight loss, Jacob believes it has advanced to at least Stage 3 but reports that medical personnel have advised him that they won’t do anything about it until it reaches Stage 4.

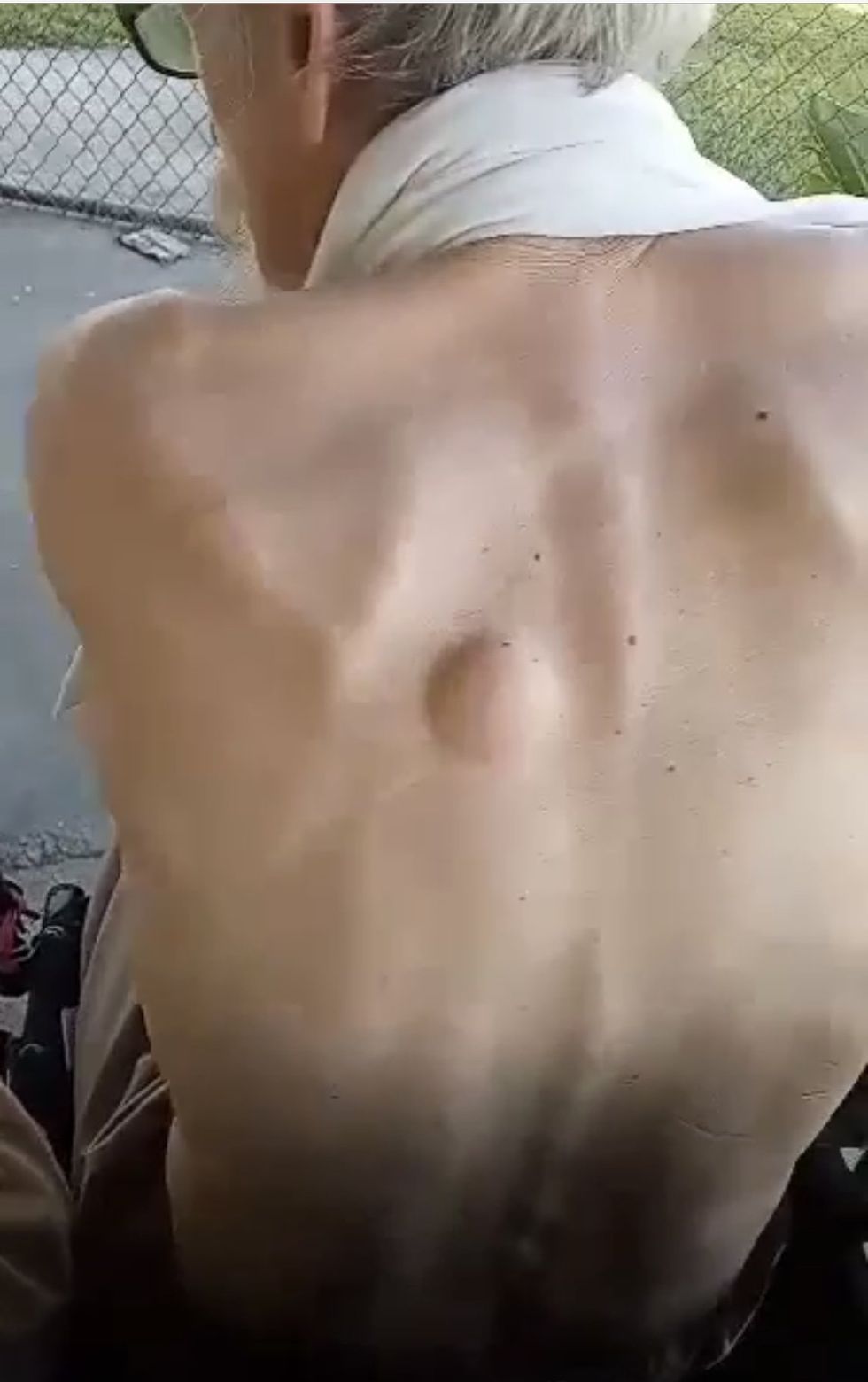

Nolan Williams, another man in the same prison, carries a burgeoning growth on his back, a golf ball that’s graduated to tennis ball size. He fears it’s cancer. Doctors have yet to order a biopsy for it.

YesCare declined to comment or answer questions about its standards and practices.

Parole is a natural safety valve for this negligence. Free to seek and receive treatment as needed, men released from prison have a chance to get at least traditional, if not optimal, care.

But Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey’s grip on the Board of Pardons and Paroles prevents that. The Board denied Smith’s bid for supervised release last year despite his record of laudable behavior and then the ADOC denied his application for medical furlough, a different method of release but the Board still plays a hand in it by deciding whether to request medical records or not.

Less than six months into her first term, Ivey signed into law HB 380, a bill passed by the Alabama legislature that ceded the control over the Board of Pardons and Paroles to the governor. Ivey alone gets to choose who sits on the Board after consulting with her inner circle of advisors. She’s set up a situation where she can install the people who will do exactly what she wants.

Denying parole to deserving applicants isn’t just an expression of Ivey’s iron-cold callousness toward the state’s wards. HB 380 is entirely unconstitutional. Ever since 1940, Amendment 38 to the state constitution ensures that only the legislature governs how pardons and paroles are doled out.

Yet upon Ivey’s arrival at the governor’s mansion, state lawmakers blatantly overrode that statute — in the House of Representatives the vote was 73 to 27 and in the Senate it was 25 to 5 — and gave up this power to the governor. The legislature lacked the authority to do this. Alabama voters would have had to vote again to amend the state constitution and vest this power in Ivey, but they haven’t.

Smith is challenging the constitutionality of HB 380 and he’s not the first to do so. There's a small indication in his appellate record of the state's interest in keeping him incarcerated. The state's brief requests the Court of Criminal Appeals issue a written decision — it hasn't in the past — to stop future litigation on this issue. No appellate party asks for a written opinion unless they're convinced they are in a favorable forum. The state's attorneys think they're going to win this one — and releasing Smith on medical furlough would make this allegedly guaranteed win go away. The issue would become moot.

Local and regional coverage of Smith’s predicament declares “Convicted Dothan killer denied release after cancer diagnosis” as if that tells the entire story. According to his sister, Travella Casey, Smith never interacted with law enforcement prior to his arrest for the death of his girlfriend, LaKendra Smith.

Smith sits at another unfortunate intersection: a failure of the educational system to teach people how to diffuse domestic disputes without violence and the National Rifle Association’s pandering to Black men’s fear of law enforcement by expanding access to firearms.

What Smith might have done to become confined is the wrong question to ask, especially for the law and order crowd. The rule of law requires that people who we hold accountable don’t get killed themselves through negligence or hatred. The Eighth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States enshrines this. That’s the law.

The proper questions are whether the Alabama appellate court system will allow Smith — and potentially others — to perish without getting the prescribed treatment because of an unconstitutional statute and whether Ivey, Marshall, Hamm and Lunsford understand that their actions are tantamount to homicide, too.

Chandra Bozelko served more than six years in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent. Her work has earned several professional awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, the Los Angeles Press Club, The National Federation of Press Women and more. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.