How To Remember The Real John Lewis — And His Righteous Struggle

Many Americans, when they remember the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, reflexively turn to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, quoting selective passages about content of character. But my sister Joan, who stood under a shaded tent that day, making signs with freedom slogans for out-of-towners to raise high, had a different answer when I asked for her thoughts. Not to take anything away from King, she told me, "It wasn't just that speech. It was all the speeches." And what impressed her teenage self most were the words of a man who was just 23, a few years older than she was.

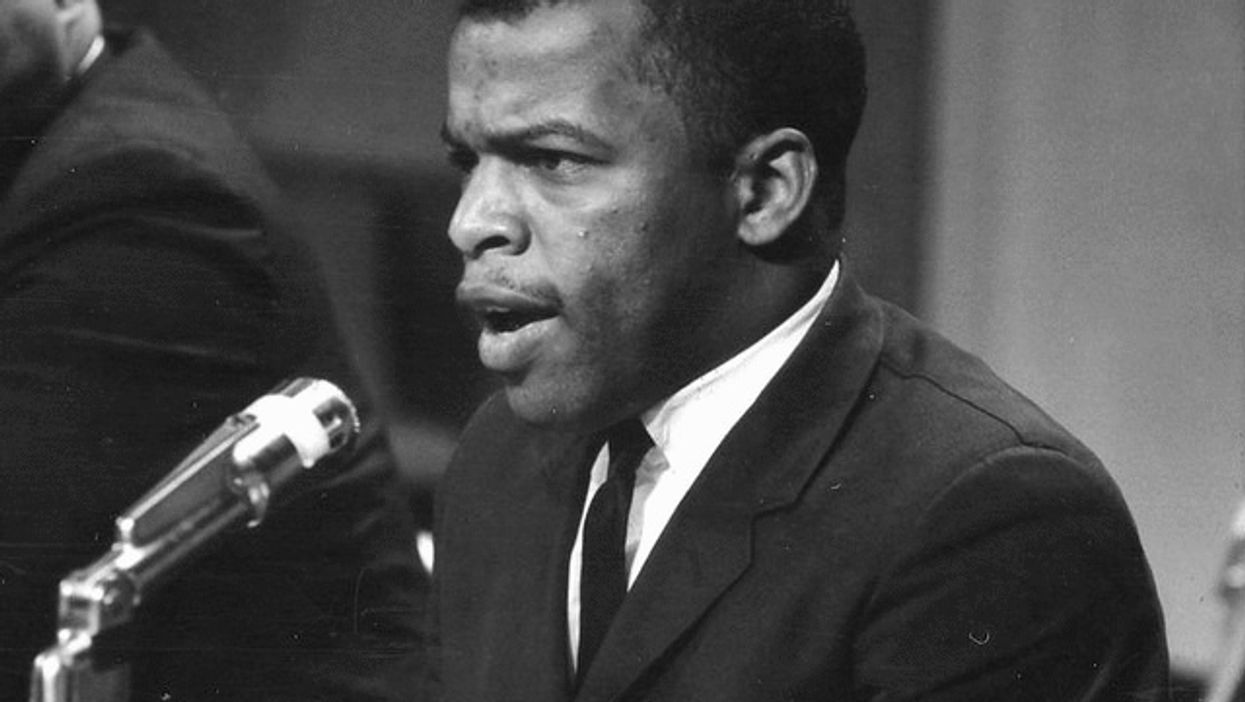

On that day, John Lewis was already stirring up the "good trouble" he favored when he said: "To those who have said, 'Be patient and wait,' we have long said that we cannot be patient. We do not want our freedom gradually, but we want to be free now!"

It was a speech that, in an early draft, was a tad fiery for some elders in the movement for equality and justice. Lewis did tone it down — but not enough to lose its urgency.

Some of the tributes to Lewis, who died last week at the age of 80, emphasized his generosity of spirit, evident in his ability to forgive and embrace those who beat him into unconsciousness. But the picture is incomplete without acknowledging the impatience, the fury to make it right, that saw him through more than three dozen arrests, five after he was elected to Congress. Just as those who would have been or probably were in that majority of Americans who considered King a rabble-rouser then and revere him now, many are all too eager to recast Lewis as a secular saint who just wanted everyone to get along.

Of course, they would. It would let them off the hook.

They could forget that when he died, Lewis was still fighting some of the same fights, especially for voting rights. Lewis said he nearly cried when the Supreme Court in 2013 invalidated key provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. States then followed with deviously clever restrictions and ruses, many, as court challenges found, designed to limit rather than expand the franchise, especially if those left out in the cold were minorities, the poor and the young.

As we've seen in primary snafus this year in states such as Wisconsin and Georgia, the long lines, creaky machines and shuttered polling spots always seem to land in heavily minority districts.

Shameless hypocrisy

Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) was quick to memorialize Lewis, acknowledging the "huge personal sacrifices" he made "to help our nation move past the sin of racism," which abdicated the power the Senate majority leader has to truly honor the man.

The fact that the House bill to strengthen voting rights sits on his desk shows how much McConnell respects Lewis' life work, though many, from House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn to California Sen. Kamala Harris have said passing the measure would be fitting tribute.

The hypocrisy is nothing new. When Lewis joined other lawmakers in a sit-in on the House floor in 2016 over an impasse in gun control legislation, Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-WI), who had held Lewis close to prove his civil rights bona fides, called it "a publicity stunt, a fund-raising stunt."

Today, McConnell and his party have pivoted to winning elections, by any means necessary, even when those means pervert the causes of Lewis and fellow freedom fighter Rev. C.T. Vivian, a giant the world also lost last week. The Supreme Court, still dominated by conservatives, recently issued a ruling that stalls former felons in Florida looking to regain their right to vote, despite the electoral wishes of the state's voters.

Lewis is not a foil to the protesters of all races marching in support of the Black Lives Matter movement after the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Those demonstrators are his spiritual children, and Lewis had said he was "inspired" by them.

President Donald Trump, downplaying a pandemic and economic upheaval, has landed on a campaign message. He screams and tweets "law and order," conflating peaceful demonstrators with those who would sow disorder, calling them "thugs" and sending federal agents to Portland, Oregon, to haul them away in unmarked vehicles. He threatens to dispatch more into cities with Democratic mayors.

Trump needs to revisit the scenes of Lewis crossing Alabama's Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965. That young man, dressed in a trench coat with a backpack over his shoulders, was quickly engulfed in a hail of baton blows that cracked his skull; he was beaten to the ground amid clouds of tear gas.

The "thugs" were state troopers whose job it was to keep the marchers in their place and out of the voting booth. The man who punched Vivian in the mouth as he tried to register to vote was an Alabama county sheriff, known to be fond of the nightstick, who operated under cover of a twisted version of "law and order."

Whose history?

Lewis and Vivian used nonviolence in the face of violence, knowing they and other civil rights workers very possibly would not make it home — and all for the sake of America.

When Trump accuses Democrats of trying to erase history, I doubt this is the history the man who defends Confederate monuments is talking about. History that would obliterate the pain and replace it with pride is false and incomplete. Study those founding documents, yes, and also acknowledge the flawed men who wrote them while living lives full of contradictions.

Any remembrance that paints a scenario of good guys and bad guys without acknowledging the hard work that keeps America trying, and sometimes failing, to live up to its ideals is no better than a cartoon, though a dangerous one.

To make democracy look too easy hides how easy it would be to lose it.

Lewis challenged America to do better while breaking laws he knew were unjust. The faces of the baton-wielding state troopers, the belligerent sheriffs on the courthouse steps and politicians who would ride racial resentment to elected office reveal they knew they were outmatched as human beings, and knew what history would make of them.

Of that famous march on Aug. 28, 1963, my sister, who is also gone now, remembered: "Such camaraderie, all these people, black and white, there were no problems. It was the mood. You knew you were part of something special, just being there. You knew things would be different."

And Lewis, the young man who would grow older but never lose the fire, said on that day: "We do not want to go to jail. But we will go to jail if this is the price we must pay for love, brotherhood, and true peace."

Not the words of an icon on a pedestal but a righteous man with demands and dreams that only change could fulfill.

Mary C. Curtis has worked at The New York Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Charlotte Observer, as national correspondent for Politics Daily, and is a senior facilitator with The OpEd Project. Follow her on Twitter @mcurtisnc3.

Trump Cabinet Nominee Withdraws Over (Sane) January 6 Comments