There was a saying in Hollywood when I worked out there in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s: To make a motion picture, first you need the written word. It was true. None of the moving images you’ve seen in a movie theater on your television would have been possible unless some writer had sat down in a room, usually alone, and written the screenplay or teleplay that told the story and described the action that would eventually fill screens for you to marvel at.

I should confess my prejudice from the beginning: As a writer, I have always believed in the power of words to inform, to entertain, to inspire, to soothe, to amaze, to stun, to motivate, to carry you away to places you’ve never been and to experience feelings you’ve never felt. Without words, we would be lost. We would not be able to communicate with one another. We would be unable to engage in commerce, to give directions, to express our love for each other or for wonderful things, even to grieve and recover from grief. Words are one of the most important things that make us human. The animal world is without them, although some species such as whales and birds and canines like wolves can “talk” to each other by making sounds that are emitted from vocal cords not unlike our own.

The Oxford English Dictionary estimates that there are currently 171,146 words in use in the English language, not to mention some 47,000 or so that were once used but have become obsolete. I don’t know the numbers for other languages, but with some 7,000-plus languages spoken around the world, there are probably two billion words in use by human beings on this planet.

Certain words are more powerful than others. The word “love” is one of them. It has been the subject of countless poems and books. It is a word found throughout the Bible and the sacred texts of other religions. The word “love” is as universal as the air we breathe. It expresses something seemingly all of us feel or are capable of feeling or want to feel.

But so is the word “hate” powerful. If words can bring us together, join us to one another individually or as a people, so can they drive us apart. Hate is one of those words. If you say you hate someone, you are expressing your apartness from that person. By hating a person or a place or an idea, you are marking it as wrong, as alien, as unlike yourself, as dangerous – a thing to be scorned, even to be destroyed.

And it is here that we enter the world of rhetoric, the art – if you will – of using words to serve the purpose of persuasion. You can persuade, or attempt to persuade, people for various reasons and in various ways. The academy, where rhetoric is studied, will tell you there are three ways to use rhetoric to appeal to an audience: As the Greek philosopher Aristotle observed, you can use “logos,” deploying reason. You can use “ethos,” counting on your own character and credibility to carry the day. And you can use “pathos,” appealing to the audience’s emotions and shared beliefs and values.

Political rhetoric, the use of words to persuade people, let us say, to be on your side rather than that of your opponent, can make use of all three corners of what they call the rhetorical triangle, involving reason, credibility (which we can read here as apparent truthfulness), and emotions. And that’s the way political rhetoric has gone practically since our country’s founding. Here are the reasons my program or policy is better than my opponent’s, and here are the reasons I’m more trustworthy than my opponent. For example, my opponent took campaign contributions from the “X” industry, so how can you trust that he will represent you and not the industry that gave the money? Here is a list of people with whom my opponent identifies, and these are the reasons his closeness to them is not in your interest. Vote for me! I will do the things I say I will do, unlike my opponent, who failed to keep his promises the last time you voted him into office.

Or politicians could decide to just sling mud and lies and hate.

There are plenty of examples of rhetoric visiting the gutter in American politics. In campaign ditties sung by troubadours – an early version of campaign advertising – John Adams accused Thomas Jefferson (accurately, as it turned out) of fathering children by a slave. Invective was slung about in campaign after campaign. Father Charles E. Coughlin, a famous “radio priest” from Detroit, at first supported President Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal. But when he turned against him, he hurled anti-Semitic attacks at Roosevelt, accusing him of being in league with “Jewish bankers” who controlled the world, and thus the American economy, to the detriment of ordinary citizens.

In the 1930s and '40s and '50s, right-wing politicians accused their liberal opponents of being communists and socialists. The examples of racism being used in American politics is long and sickening. In recent times, there was the so-called Willie Horton ad used against Michael Dukakis by George H.W. Bush. And the infamous Jesse Helms ad showing a pair of white hands crumbling up a job rejection letter with a black hand clearly shown on the letter and a voiceover explaining that he didn’t get the job because of racial quotas. Helms’ opponent in the Senate race in North Carolina was Harvey Gantt, who was Black.

I’m sure you can come up with examples of your own of what used to be called dirty politics through the years. But except for the vicious rhetoric which preceded the Civil War over slavery, when southern states under the banner of the Democratic Party banded together to attack northern politicians, Lincoln chief among them, the harshest rhetoric in American politics was more or less one-on-one, with individual candidates making nasty accusations against their opponents.

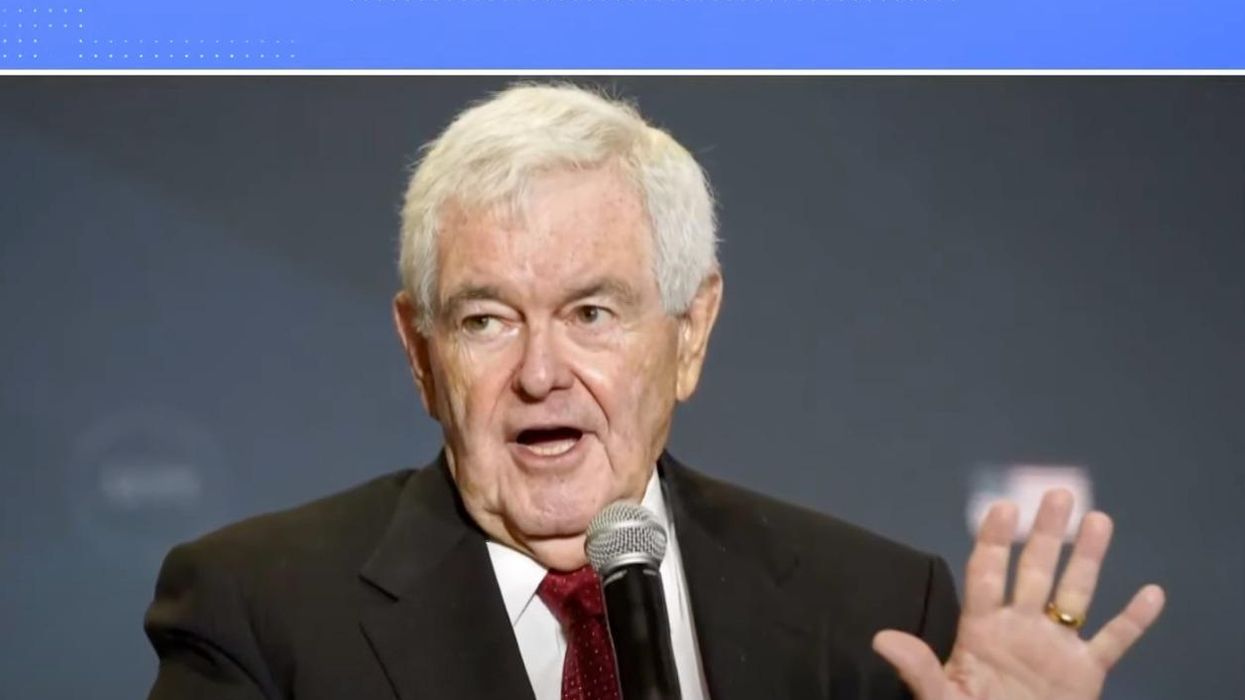

Until 1990, that is, when Newt Gingrich, using GOPAC, a Republican organization put together to help train and fund GOP candidates for office, began his campaign to elect Republicans to Congress who would one day elect him Speaker of the House. In service of that singular cause – Gingrich made it sound like it was about Republican ideas and programs, but it was really all about himself – he released a memo put together with the help of Republican pollster Frank Luntz. The title of the memo was “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control.” The memo was written because so many Republican candidates had told GOPAC organizers, “I want to speak like Newt,” who was then making fiery speeches on the House floor, usually to an audience that consisted of the House video cameras and zero members. The speeches made his reputation for using negative words and attack phrases meant to divide, diminish, distract, and destroy political opponents, namely Democrats and the Democratic Party.

The Gingrich memo codified Republican negative attack politics and was notable for language that was at the time called vicious and nasty, not to mention negative and outrageous. From the perspective of the week that Nancy Pelosi’s husband was attacked with a hammer by a right-wing extremist follower of Donald Trump who had posted long diatribes against Jews, the LGBTQ community, Blacks, and immigrants, the Gingrich memo seems to float into view on a pink cloud of lost innocence.

The memo has two lists of words Luntz had tested with focus groups to determine their political efficacy. The first was a list of “Optimistic Positive Governing Words,” meant to “help develop the positive side of the contrast you should create with your opponent, giving your community something to vote for!” It included words like building, caring, change, children, courage, crusade, commitment, family, fair, freedom, hard work, incentive, liberty, opportunity, peace, precious, preserve, principle, prosperity, protect, pride, reform, strength, tough, truth, we/us/our.

The second list, entitled, “Contrasting Words,” was meant to “define our opponents” and be applied to Democrats’ “record, proposals, and their party.” Here we go with the attack vocabulary according to Newt Gingrich: abuse of power; anti flag, family, child, jobs; bizarre; cheat; bosses; bureaucracy; corrupt; criminal rights; decay; destroy; destructive; disgrace; greed; failure; incompetent; intolerant; liberal; lie; pathetic; permissive; radical; selfish; self-serving; shallow; shame; sick; steal; taxes; they/them; traitors; unionize, waste; welfare.

The words themselves were not as remarkable as the fact that one of our two political parties made a decision at its highest levels to abandon persuasion in favor, essentially, of name-calling and attacking the other side not just as wrong on the issues, but as a group of “them” who were not as genuinely American as “us.” The fact that it was an organized effort to marshal a way of attacking the other side began to infect everything about the Republican Party.

An activist by the name of Grover Norquist, who ran a Washington D.C. lobbying outfit with the innocuous name of Americans For Tax Reform, began holding Wednesday morning coffee klatches for Republican campaign advisers, staffers, and legislative assistants on Capitol Hill, and he handed out what became known as “talking points” for the week to come. The Republican Party would speak with one voice for the next seven days about tax cuts or deregulation or what they termed “extreme” environmental policies, or whatever Norquist and other Republican organizers came up with. They would pepper their talking points with Gingrich’s attack words, and they would hammer their weekly message home with repetition ad nauseum. You would turn on a political program on television, and every Republican would be mouthing not just the party line in general, but a specific party line. And then next week, the talking points would change, and they would mouth a new one.

The words and the talking points worked. The Republicans took control of the House for the first time in decades and Gingrich was elected Speaker. Throughout the 1990’s and into the 2000’s, you could detect a difference in the way politics was practiced by Republicans as they deployed Gingrich’s attack words to demonize Democrats and label them as against everything “we” stood for. They were supposed to be used to contrast “good” Republicans from “bad” Democrats, and that is exactly what happened.

That is until, over time, the Gingrich list wasn’t nasty enough. Democrats became the enemy, or in the words of Donald Trump, the “enemy of the people.” Democrats are now “evil” and “in league with the Devil,” and not just anti-flag and anti-family, but “anti-God.” Democrats are going to “take your guns,” when no such policy has ever been proposed by any Democrat running for any office. And naturally, Democrats and any person straying from the Trumpian truth and narrow are now labeled as pedophiles, including a fellow Republican, former Arizona Speaker of the House Randy Bowers, who refused to go along with Trump’s charge that the election was stolen in his state. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, after she had been nominated to the Supreme Court, was smeared by Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri as being sympathetic to pedophiles because several prison sentences she had given child abusers were deemed not long enough. A rumor that a Democratic Party pedophile ring was headquartered in the basement of a Washington, D.C, pizza restaurant spread so fast and so far that the inevitable happened: An armed man showed up one day and shot up the place looking for all the pedophiles.

An entire movement, if it can be called that, QAnon, sprang up around the idea that leaders in the Democratic Party are conspiring to kidnap children, abuse them, kill them, and then drink their blood because of its “anti-aging” qualities. This charge has been levied against Nancy Pelosi by Republican candidates for office. Other Republicans like Marjorie Taylor Greene have labeled Pelosi a “traitor” and called for the “death penalty” for her. One Republican congressman ran an online ad showing him shooting a gun at a firing range with a voiceover calling for “firing” Nancy Pelosi. He was asked in a television interview if it wasn’t true that he was encouraging people who perhaps were not completely in control of themselves to take their guns and actually “fire” them at Nancy Pelosi or other Democrats. It had become so commonplace for guns to be brandished in Republican campaign ads by now that he just shrugged.

And so it has come to pass that this week we’ve got Elon Musk, the new owner of Twitter and the world’s most wealthy man, as well as numerous Republican elected officials, gleefully spreading vicious lies that the attack on Paul Pelosi was somehow a gay tryst gone wrong. The garbage right-wing website they linked to just made stuff up. But Republicans linking to the site and Musk himself have become expert at using a kind of code to get across their hateful disinformation. It frequently takes the form of raising an apparently innocent question: I’m just asking, could this be true? Then they cite the lies they want to put across.

In his tweet about the attack on Paul Pelosi, Musk used another common way of spreading extremist lies: He didn’t come right out and endorse the story he linked to, but rather said “there is a tiny possibility there might be more to this story than meets the eye.” It’s the I’m just sayin’ scam writ large. The entire Republican Party has become adept at using the language Trump has employed when he wants to spread a story he knows to be untrue – people are saying, or I’ve heard from people who say. There are half a dozen wordings for the scam, but all serve the same purpose. Neither Trump nor any of the other Republicans who put across lies in this fashion have heard anything of the sort, but once they say it, everyone will hear it. That’s the point. A lie is no good unless it is spread widely, and they’re experts at moving lies around the information ecosystem.

I heard a Fox News host “just asking” why Paul Pelosi’s attacker had been jailed without bail when “lots of people hit other people with hammers,” and they don’t get arrested and held without bail, implying that because the attacker’s victim is the husband of Speaker Nancy Pelosi, he is being singled out by prosecutors and discriminated against. The Fox News talking-head didn’t have to tell his viewers what they had been trained to know already: It’s the libs going after a man just because he’s a conservative.

It has become a common refrain from Republicans and their followers on the far right: They call the Trump mob that assaulted the Capitol “patriots” and claim they are being treated more harshly than liberals or Antifa or Black Lives Matter protesters would be treated for committing the same offenses. It’s utter nonsense, of course, but Republicans regularly spew such a miasma of hate and nastiness that it has become normalized, just another day in American politics. Some of the hate and lies are right out there in antisemitic memes and racist tropes and violent imagery like shooting guns. Other Republican rhetoric is coded or put in the form of “innocent” questions, but all of it is toxic, and its growth and volume have turned politics in this country dangerous.

This is how far things have gone: There are armed men in camouflage outfits and bulletproof vests standing watch at ballot drop-off boxes in Arizona. A state court judge recently refused to ban this blatant form of voter intimidation and called it “free speech.”

My friend Charlie Pierce in his Esquire column yesterday referred to the entire phenomenon of the Republicans’ descent not just into violent rhetoric but violence itself as “the prion disease [that] has jumped from one subject population to the general public, and in too many ways, it is creating its own reality in the national mind.”

“We are all lost and mad,” Charlie lamented. I can understand why he feels that way. I could continue this brief history of the descent of Republican political rhetoric into a radical politics that embraces anti-democratic principles and movements and leaders like the ones in Hungary and Italy, but enough is enough. It makes me physically ill to go back through this stuff and write it down for this column.

I would part ways with Charlie Pierce in one way, however. The prion disease infecting the Republican Party is a metaphor derived from mad cow disease that can destroy whole herds if not caught and treated.

But mad cows catch the disease from infectious agents in the wild. Republicans have administered the disease to themselves, beginning with Gingrich’s memo more than 30 years ago, and the virus has mutated and turned deadly. There was a purposeful takeover of the politics of a political party that used to be part of our democratic system but is no longer. It is now a fascist party that is actively spreading a political disease that can kill our democracy and has already killed some United States citizens. The political ravings of Vladimir Putin about Ukraine would be right at home in the Republican Party of today. In fact, they already are.

It has gone beyond rhetoric, folks. To the Republican Party and its leaders, Democrats are not fellow citizens to be persuaded but a people with whom they are at war who must be destroyed. There have been enough guns in enough Republican political ads recently that it’s not just a phenomenon, it’s a fact. Even with all their voter suppression and gerrymandering and threats at ballot drop boxes and lies about Democratic voter fraud, if Republicans can’t beat us at the ballot box, they’ll encourage their loon followers to “be wild” and “fire” us.

After years of hateful and violent rhetoric, they’ll know exactly what to do.

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist, and screenwriter. He has covered Watergate, the Stonewall riots, and wars in Lebanon, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels. You can subscribe to his daily columns at luciantruscott.substack.com and follow him on Twitter @LucianKTruscott and on Facebook at Lucian K. Truscott IV.

Reprinted with permission from Lucian Truscott Newsletter