Smuggled Photos Depict Starvation Diet Inflicted On Alabama Prisoners

This is the second in a series of columns about the current crisis in Alabama’s prisons. Read the first here and the third here.

“You know, my wife, when I packed my bag for the prison the last probably, I'd say, five or six nights. I would pack six half peanut butter sandwiches in my bag. My wife's like ‘You're not eating those sandwiches, are you?’

"And I said ‘No, I'm not.’

"I said ‘It's for the diabetics in the event they fall out.’”

Former Alabama gubernatorial candidate Stacy Lee George was a correctional officer at Limestone Correctional Facility, Alabama’s largest and highest security prison for more than 13 years. He resigned because of an old injury on October 26, 2022, when the Alabama prison strike — a period of about one month where inmate workers had refused to work to bring attention to the draconian sentencing structures in the state — had been put on hold.

From the outset of the strike on September 26, none of the demands had anything to do with prison conditions. Rather, strikers wanted to eliminate life-without-parole sentences, creating oversight over the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles and establishing new parole eligibility criteria for release, among other demands.

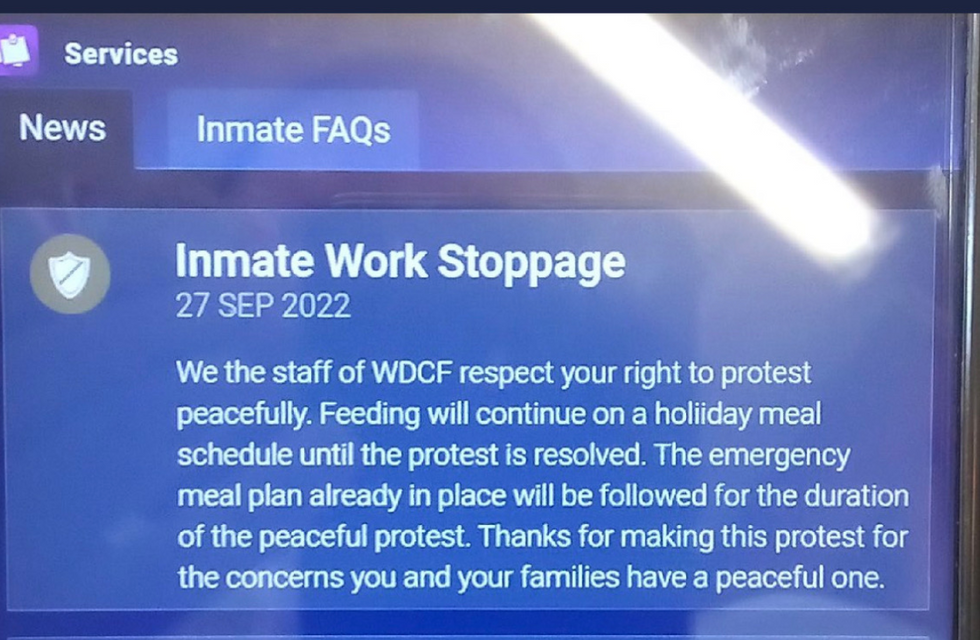

Upon hearing of the strike, administrators posted a notice to inmates at William Donaldson Correctional Facility in Bessemer, Alabama that houses 1362 men.“Feeding will continue on a holiday meal schedule until the protest is resolved. The emergency meal plan already in place will be followed for the duration of the peaceful protest, Thanks for making this protest for the concerns you and your families have a peaceful one (sic).”

It seemed like a reasonable concession — if employers were in the habit of well-wishing their own workers a good strike. Holiday or reduced feeding schedules are legal per the 1978 Supreme Court decision in Hutto v. Finney. And the Alabama Department of Corrections facility said it simply didn’t have enough guards to fill the kitchen positions vacated by the strikers. On the surface, a reduced distribution schedule seemed reasonable.

But that wasn’t the extent of emergency or holiday meal management. Wardens reduced the amount of food and the number of calories served to the people incarcerated in all of the state’s fourteen prisons.

According to firsthand accounts, some meals were simply four pieces of bread with an unknown condiment on them.

.

One picture shows a man with a black styrofoam tray with five sections; three are empty, clean of any sustenance whatsoever, and one contains applesauce and another appears about a third full of a stew-like concoction.

Another meal is two peanut butter and jelly sandwiches (peanut butter and jelly are mixed so that the jelly can’t be used to make alcohol).

Another meal photographed by an unnamed source is one slice of cheese, a small serving of canned fruit cocktail, and approximately one-half cup of grits as another meal.

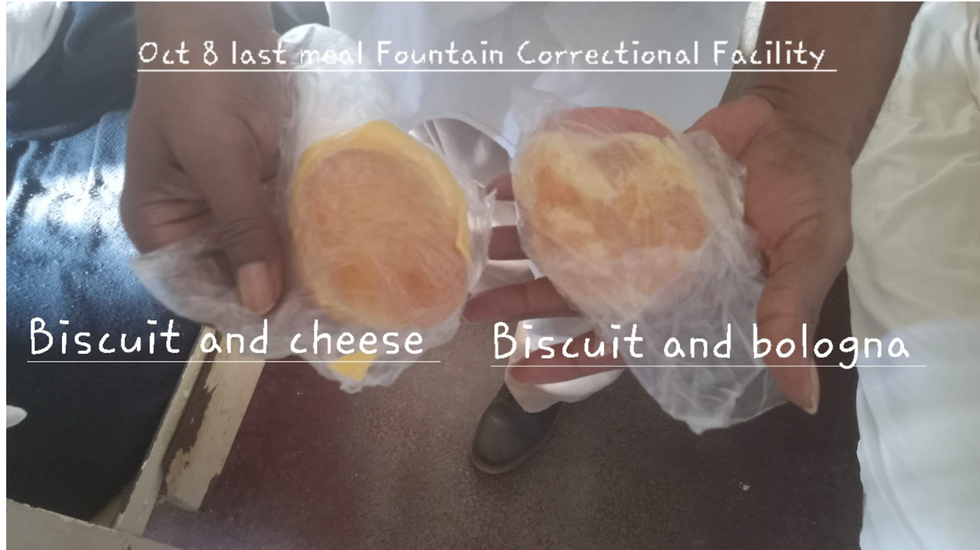

Another meal at Fountain Correctional Facility in Atmore, Alabama consisted of two biscuits, one slice of cheese and one slice of bologna.

The calorie counts of these meals ranged from 291 to 655 per meal. Federal dietary guidelines suggest that between 2,000 and 3,000 calories per day are appropriate for adult men and between 1,600 and 2,400 daily calories for adult women. Energy expenditure tends to raise caloric needs but even sedentary males over age 18 need at least 2000 calories per day, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

It wasn’t just the meager fare; it was the time between distribution of meals. During the strike, George worked in the segregated housing unit where the first meal was served at four in the morning and the next one wasn’t delivered until eight o’clock at night.

George describes two major problems developed from the extreme spacing between meal distribution times and the lack of food: the effect on prisoners who take psychotropic medications and diabetic inmates. Without a steady or sufficient amount of food in their stomachs, prisoners who took psychiatric medications or who are diabetic would vomit often.

Failing to take food with certain psychiatric medications can have serious clinical consequences. Some antidepressant and anti anxiety medications — buspirone (BuSpar), the antidepressants Zoloft and Viibryd, and the mood stabilizer lithium depend on food at the time of administration for their effectiveness. When swallowed, two antipsychotics specifically, ziprasidone (name brand Geodon) and lurasidone (name brand Latuda) — require about 500 calories in the patient’s stomach for optimal absorption.

“In most cases, if directives aren't followed and the medication isn't taken with food, the medication may be less effective (i.e., a lower blood level). In conditions like Bipolar disorder, this can be especially dangerous, as small changes in blood level can sometimes have major impacts on medication effectiveness and clinical status,” said Andrew D. Carlo, MD MPH, a Health System Clinician in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Of the 76 men in the restricted housing unit George manned during the strike, about 20 to 25 of them took psychiatric medication; George knows this because he had to accompany the nurse who dispenses the pills to the men to each of their doors.

George estimates that about one third of the 2300 men in Limestone Prison take such medication.

In 2015, in the context of a lawsuit filed against the Alabama Department of Corrections over the inadequacy of mental health care in Alabama prisons captioned Braggs v. Dunn, a federal judge found that about 3400 of the state’s prisoners received treatment either in the form of medication or psychotherapy, a number that the judge estimated to be about 20 percent of the prison population.

Alabama currently incarcerates 23,484 people; about one fifth of that count would indicate that there may have been 4696 people who may have needed medication and food to make it work properly during the strike.

The stakes are high with missed medication doses.

“When they go too long without… taking their psychotropic medicine in the past one instance I had, I had them all around with a noose around their neck. I mean, I'm looking in this cell and, you know, they got a noose hanging around their neck,” George said.

The diabetic prisoners struggled as well with the reduced food, although George didn’t witness any of them pass out. That was partially due to the sandwiches he passed out to preempt the effects of low blood sugar in the diabetic prisoners.

“Nobody really realized the impact that the food shortage had until about two weeks after the strike was over. About two weeks after the strike was over, we had about 10 to 12 inmates in the hospital,” George explained.

“So what happened was. he results of what happened there and the minimum amount of food was given. It made extensive hospital stays. Some of them were diabetic. Their sugar was so far off that they had to leave in the hospital for four days...One of them, his sugar was so far off it took three days to regulate it back down. And he would throw up every time food would touch his mouth and after he got there, he couldn't eat a bit of food for three days at the hospital. He was given an IV because his sugar had gotten so far off,” George said.

Eventually, organizers paused the strike because the effects of ADOC’s inducing hunger and illness posed danger to their wards.

That doesn’t mean that resentment doesn't linger in the state’s prisons or this chapter is over. George recently insisted the Alabama National Guard be called in to fix what’s ailing Alabama prisons. According to him, a guard from the Limestone Correctional Facility underwent emergency surgery on November 19, 2022 for a broken jaw, broken teeth and a head injury.

His assailant hit him in the head with a food tray.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.