Reprinted with permission from DC Report

Now that his term finally is over, let's examine Donald Trump's performance on a key promise: reclaiming manufacturing jobs, especially from China and Mexico, to raise U.S. wages.

Evaluation first, then a grade. (Can you guess?)

Our trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, last summer praised several companies that dropped plans to move jobs offshore. The "era of reflexive offshoring is over," he claimed in a New York Times op-ed last May.

Facts show the opposite. Team Trump encouraged offshore manufacturing, not that you'd likely know that from following the news.

In his State of the Union address last year Trump proclaimed a "blue-collar boom." It was fact-free nonsense. It didn't happen, not even before Trump's incompetent and malicious pandemic response threw 10s of millions of people, including many factory workers, onto the unemployment lines.

"Even before the coronavirus outbreak, the promised benefits of the president's $1.9 trillion tax cuts hadn't materialized and manufacturing had fallen into a slump," Rep. Don Beyer, a Virginia Democrat, wrote in a report. "After a brief upturn in 2018, manufacturing had fallen into a slump by the first quarter of 2019."

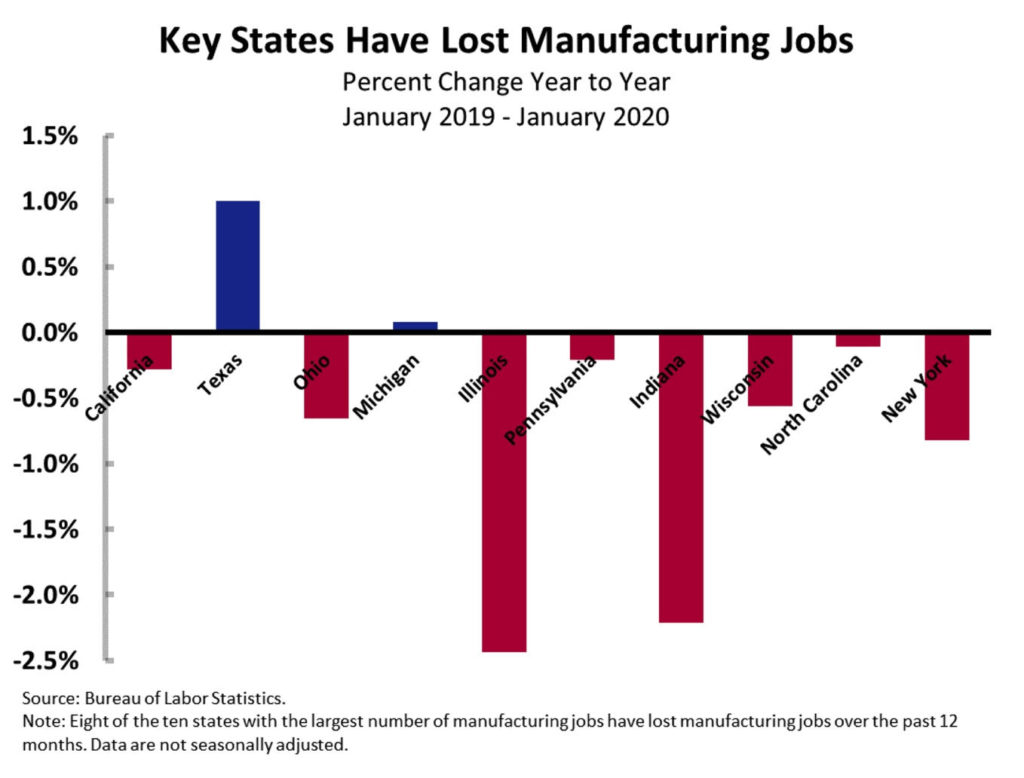

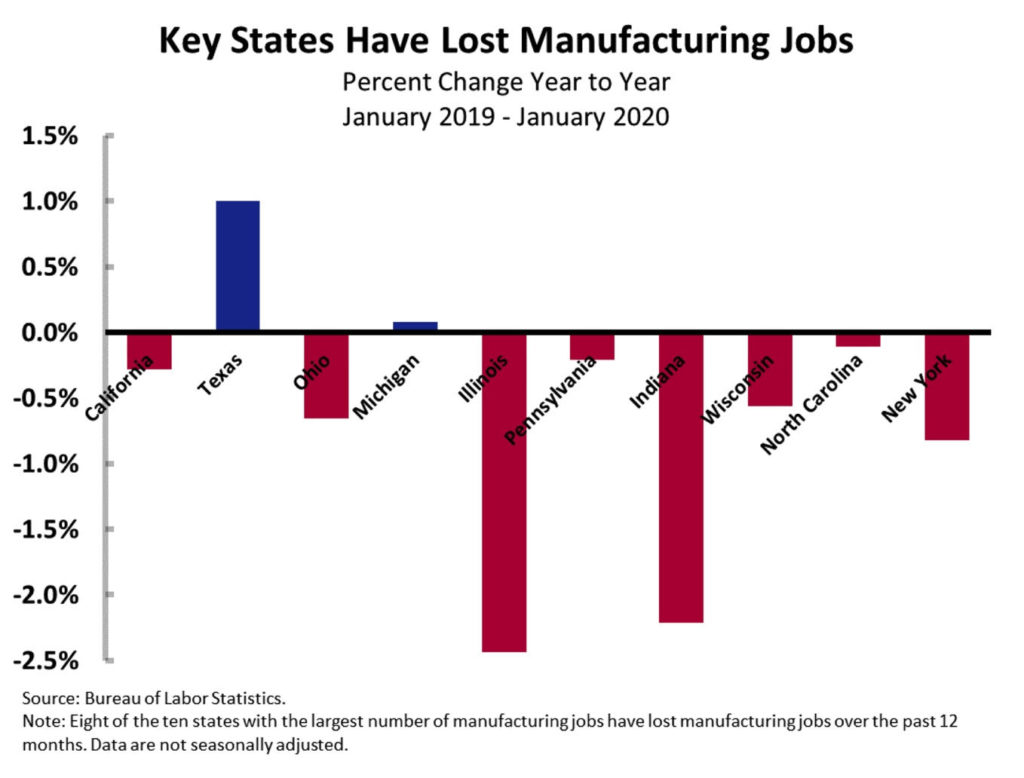

Factory job losses continued in 2019 as federal Bureau of Labor Statistics data show:

Our goods trade with Mexico had a negative shortfall of almost $101.4 billion in 2019. That's 60% worse than the $63.3 billion shortfall under the Obama administration in 2016.

Using 2019 as the benchmark avoids pandemic effects. But data on the first three months of 2020, before the pandemic, show our trade deficit with Mexico was exploding, up 21% in one year. That shows the abject failure of Trump's Mexico trade policy measured on his terms.

Job Quality Suffered

Yes, China lost jobs … to Vietnam and other countries with even cheaper labor costs.

Under Trump job stability and quality – pay, fringe benefits, working conditions – suffered.

"Job quality in the U.S. remains tepid," the Coalition for Prosperous America reported this month. The coalition promotes balanced trade deals. Jeff Ferry, the coalition's chief economist and creator of its Job Quality Index, said on Jan. 8 that "restoring the health of our manufacturing sector is the best way to restore prosperity to millions of middle class and struggling Americans."

Trump's 2016 campaign promises about manufacturing jobs raised the hopes of people who worked in the 91,000 American factories that have closed since 1997 under Congressional policies which in some cases subsidized moving jobs offshore.

But the carnage continued. In the two years from 2016 under Obama through 2018 under Trump 1,800 American factories closed.

Overall, we suffered a net loss of more than 91,000 manufacturing plants and nearly 5 million manufacturing jobs since 1997. Nearly 1,800 factories have disappeared during the Trump administration between 2016 and 2018.

Trump's 2017 tax cut added to those subsidies by enabling American firms to earn untaxed or minimally taxed profits so long as they invest offshore.

Minorities were hardest hit by the loss of factory jobs to China. Economist Robert E. Scott, who tracks trade issues for the Economic Policy Institute, estimated that 958,800 minority factory workers were displaced with wage-related losses of $10,485 per worker – and that was in 2011. Today jobs and pay are worse, not better, for blue-collar minority workers.

Weak Demand

The problem with Trump's promise and the wish for more factory jobs is with the two sources of such manufacturing jobs.

One is the diminished demand for goods, which in turn reduces the demand for workers to make, package, ship and market those goods. The other: Advances in efficiency that reduce the number of workers needed to produce goods.

Demand is weak because 90% of Americans — before the pandemic — were losing ground as the cost of living grew faster than incomes and job security evaporated in one industry after another.

The failure of political leaders in both parties to adapt to the long-running shift from factory jobs that paid well because of union contracts to moving manufacturing work offshore began long before Trump. So did the rise of low-paid unskilled and semi-skilled jobs, which has devastated the finances of most families. Trump promised voters he would reverse these trends.

The bottom 90 percent of Americans had less real income in 2018 than in 1973, the peak year for the share of production jobs in union shops. The 2018 households collected 4% less money than the 1973 households, the equivalent of having no income for the last two weeks of 2018.

Even worse for most Americans, incomes fell under Trump despite his baseless claims of huge income rises, often uncritically repeated in news reports.

In 2018 the nearly 87 million taxpayers making less than $50,000 had to get by on $307 less per household than in 2016, the year before Trump took office, my analysis of the official data shows. The gains were further up the income ladder.

That 57 percent of American households were better off under Obama contradicts Trump's often-repeated claim he created the best economy ever until the pandemic. To be sure there was a lot of income growth but it was largely among the fast-growing ranks of $1 million and up households. Their numbers grew 27 percent in 2019 compared with 2016, IRS data show.

The economic pain for most can be seen in broad economic changes that disfavor manufacturing workers, especially those in the 97,000 factories that have closed since 1997. Overall, manufacturing workers make more than service workers.

Minimum wage for waiters is just $2.13 an hour.

In December the average weekly wage for manufacturing workers was $955, compared with $823 in the service sector. That's an $8,700 annual difference. Factory workers also are more likely to have retirement plans, including the fast-disappearing traditional pension, making their total compensation even greater than the wage data show.

And thanks to former President Bill Clinton and a Tea Party activist, the late Herman Cain, since 1993 the minimum wage for wait staff has been frozen at $2.13 an hour—just $1.18 in today's money. Food server is the fifth most common job in America. Whatever these workers get above that comes from tips —when they have work.

With most workers in the lower-paying service sector, and wages for all but the top 25 percent or so of workers flat to falling for decades, people simply do not have the capacity to buy more manufactured goods. The advent of seven-year zero-interest loans for new cars and trucks doesn't hint at that, it screams demand is weak.

Increased Efficiency, Fewer Jobs

The second factor in shrinking manufacturing jobs is efficiency.

In December, America had 12.3 million manufacturing jobs, the same as in the summer of 1941 just as America entered World War II. Back then America had 204 million fewer people than now.

Factory jobs peaked at 19.5 million in 1979 when Jimmy Carter was president. There were 103 million fewer Americans then.

In 2020 we lost 577,000 manufacturing jobs, a huge toll not just on those workers but on the communities where they are concentrated.

We experienced a net loss of manufacturing plants (establishments) in every year since 1998.

Fewer workers can make more goods because refining manufacturing processes enables owners to use capital rather than labor to make things.

Capital Replaces Labor

Professor Robert Ashford, my colleague at Syracuse University College of Law and an advocate of paying all workers partly with shares of stock, explains how capital replaces labor with a simple story:

A poor young man gets a job hauling sacks of grain across town and out of his meager pay saves enough money to buy a donkey. Now he can carry more grain sacks which means he can save more so he buys a cart for the donkey to pull. With his even greater income, he next buys a truck to haul tons of grain each day. Along the way, labor is performed by capital in the form of a donkey, a cart and a truck.

When steel was first created in India about 3,000 years ago, it took years of labor to create one ton of steel. Today it takes under 40 minutes. The high cost of steel explains why in the ancient world the commanders of conquering armies were far more interested in tribute paid in that durable metal than gold and jewelry. The efficiency of steelmaking today is why the ranks of steelworkers have shriveled, especially in the last half-century.

Similarly, American lumber mills that in the mid-20th Century required hundreds of men now operate with only a dozen or so workers, including front office staff. That was thanks to computerized cranes and saws paired with lasers which measure logs to get the maximum yield in board feet of finished lumber.

The efficiency trend is likely to accelerate, not diminish. Trump's rhetoric about manufacturing jobs is as hollow as proposing a job stimulus by banning earth-moving equipment to create jobs for men wielding shovels. Or demitasse spoons.

A related problem was Trump's intense focus on China. It missed how America's trade imbalance with Vietnam is growing and how rising labor costs in China are causing it to lose factory jobs to Vietnam.

"Vietnam is gaining massive traction into the U.S. manufactured goods business," said the Coalition for a Prosperous America's Kenneth Rapoza. That's because labor is cheaper in Vietnam than in China so even some Chinese firms are shifting production there.

The key trend, Rapoza wrote: "China is slipping in our supply chains, but Mexico and Vietnam are largely taking their place."

So, overall, and considering only the period before the pandemic began, while Trump's rhetoric got him votes from desperate and gullible citizens in 2016, he oversaw fewer factory jobs and less pay for all but highly paid workers. It's the opposite of his promise.

The grade Trump earned on returning manufacturing jobs and raising pay?

F.