Mark Z. Barabak, Los Angeles Times

In 1984, Gary Hart experienced the whole meteoric-crash-and-burn phenomenon in textbook fashion.

The Colorado senator and dark horse presidential candidate finished a distant second behind then-Vice President Walter Mondale in the 1984 Iowa caucuses, losing 49 percent to 17 percent. But in the odd alchemy of presidential politics, Hart was declared the “winner” of the caucuses — despite the 32-point blowout — because he held Mondale below 50 percent and outperformed “expectations.”

Hart went on to win the New Hampshire primary and emerge, for a time, as a serious challenger for the Democratic presidential nomination until a slow unraveling that involved a series of nagging questions about the self-portrayal he put forth in his campaign. He had, for instance, shaved a year off his age, shortened the family name from Hartpence to Hart and altered his personal signature several times.

Small stuff, maybe, but eventually the inconsistencies added up to big questions about the heretofore little-known Hart, exacerbated by his vague and unsatisfying explanations — to keep our scandals straight, it was four years later that his presidential prospects sank, once and for all, in the wake of an apparently adulterous relationship aboard the aptly named yacht Monkey Business.

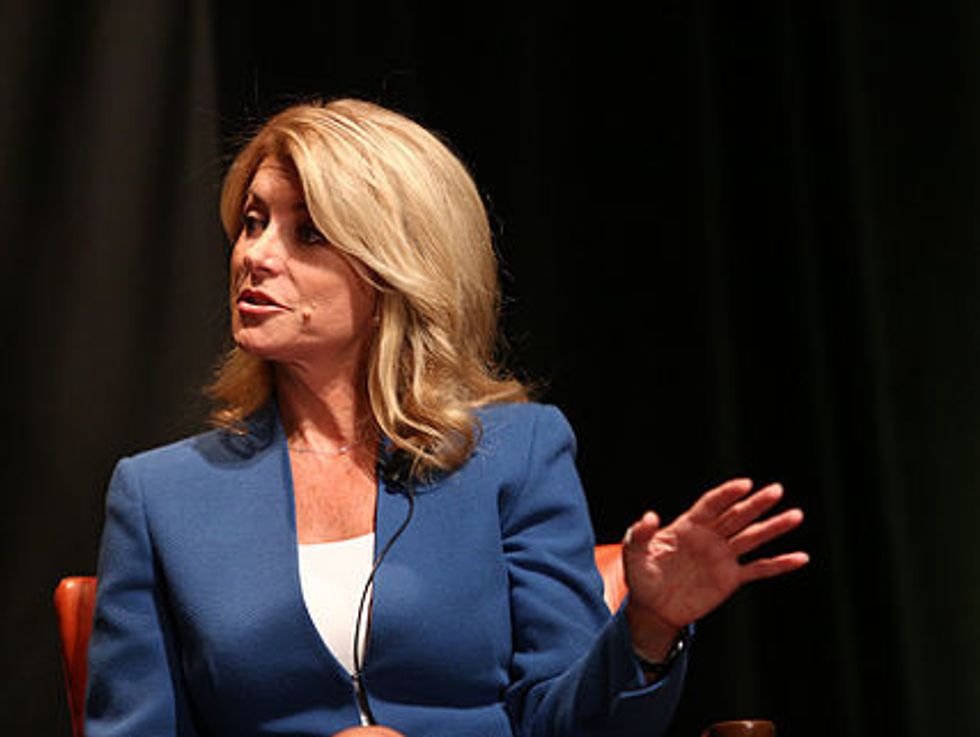

Now Wendy Davis, another meteorically risen candidate, is undergoing the flyspeck scrutiny of a big-time campaign and explaining away small but nagging inconsistencies in a personal story that, far more than Hart’s, has been instrumental to her early success.

Davis, the Democratic hopeful for Texas governor, burst on the national scene last summer after filibustering to briefly block state passage of stiff anti-abortion legislation. Her physical stamina was impressive, but even more so was Davis’ bootstrapping back story: a divorced single mom rising from the trailer park to Harvard Law School and a successful legal and political career.

Then on Sunday, veteran Dallas Morning News political reporter Wayne Slater published a story raising some questions about the details and chronology of the story Davis and her campaign have put forth.

The essentials are true: a hard-luck background, serious obstacles, personal striving, substantive achievement. But it turns out Davis was 21, not 19, when she divorced, and she lived in a mobile home for only a few months before moving into an apartment with her daughter. Her second husband helped pay for her final two years of college and her Harvard education, a fact omitted from her campaign website, which mentioned only academic scholarships and student loans.

None of that is likely to sink Davis’ gubernatorial candidacy, in and of itself. But the dustup hardly helps. When a candidate’s appeal is so heavily reliant on biography, it’s important to get the basics right — especially as voters are just getting to know a candidate.

“My language should be tighter,” Davis told the Morning News in an interview. “I’m learning about using broader, looser language. I need to be more focused on the detail.”

On Monday, Davis released a chronology of her life, along with a flurry of tweets and a statement: “I’ve always been open about my life not because my story is unique, but because it isn’t.”

No candidacy goes entirely smoothly, and it is to Davis’ great benefit that the question marks about her background surfaced in January rather than July. But if a pattern of shaded truths or inconsistencies emerges over the coming weeks and months, an already difficult contest could quickly slip beyond the Democrat’s grasp.

Just ask Gary Hartpence.

Photo: The Texas Tribune via Flickr