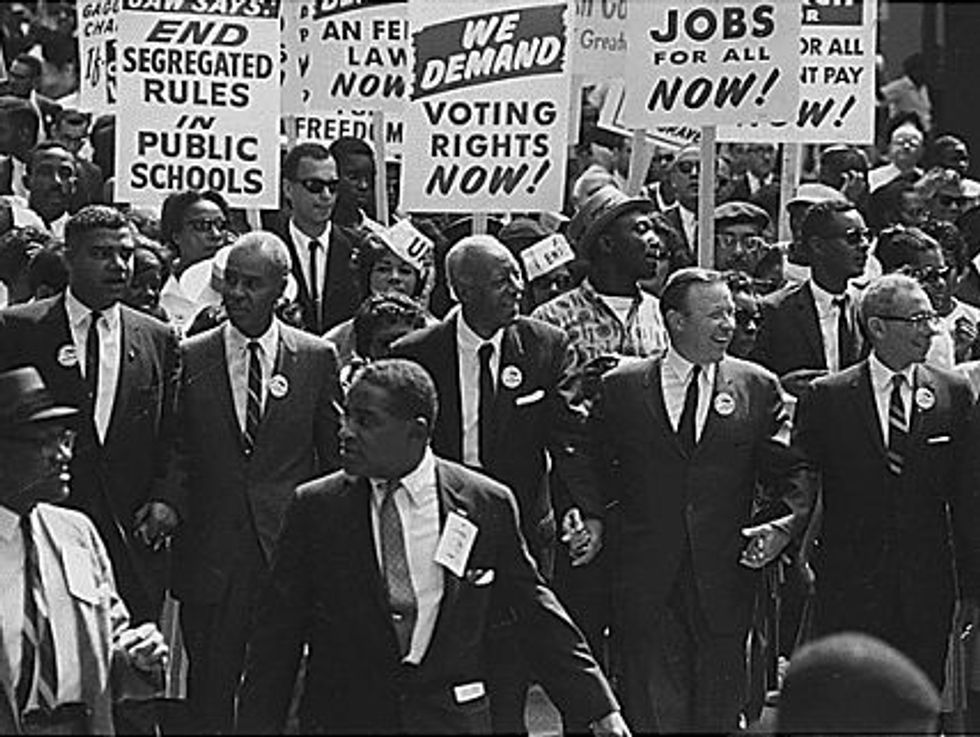

WASHINGTON — The things we forget about the March on Washington are the things we most need to remember 50 years on.

We forget that the majestically peaceful assemblage that moved a nation came in the wake of brutal resistance to civil rights and equality. And that there would be more to come.

A young organizer named John Lewis spoke at the march of living “in constant fear of a police state.” He would suffer more. On March 7, 1965, Lewis and his colleague Hosea Williams led marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL. They were met by mounted state troopers who would fracture Lewis’ skull. As we celebrate Lewis’ ultimate triumph and his distinguished career in the House of Representatives, we should never lose sight of all it took for him to get there.

We forget that the formal name of the great gathering before the Lincoln Memorial was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Jobs came first, an acknowledgement that the ability to enjoy liberty depends upon having the economic wherewithal to exercise our rights. The organizing manual for the march, as Michele Norris points out in Time magazine, spoke of demands that included “dignified jobs at decent wages.” It is a demand as relevant as ever.

We forget that many who were called moderate — including good people who supported civil rights — kept counseling patience and worried that the march might unleash violence.

King answered them in the oration that would introduce tens of millions of white Americans to the moral rhythms and scriptural poetry that define the African-American pulpit.

“We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now,” King declared. “This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.” How often has the opiate of delay been prescribed to scuttle social change?

King’s dream speech was partly planned and partly improvised, as Taylor Branch reported in Parting the Waters, his book on the early King years. One reviewer of the speech, a principal target of King’s persuasion, pronounced it a success. “He’s damn good,” President John F. Kennedy told his aides in the White House.

He was. King’s genius lay in striking a precise balance between comforting his fellow citizens and challenging them. Like Lincoln before him, King discovered the call for justice in the promises of our founders.

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” King said. “This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” King’s dream was the latest chapter in our story. “It is a dream,” he insisted, “deeply rooted in the American Dream.”

We also remember how profoundly colorblind King’s dream was. He looked to a day when “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls.”

We forget that the passage immediately preceding his description of those happy children was a sharp rebuke to the state of “Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words ‘interposition’ and ‘nullification.'” He was referencing discredited states’ rights notions invoked to deny the rights of Americans of color. I intend no offense here toward Alabama. But we should recognize the origins of slogans still widely used today to thwart the advance of equal rights.

And at a moment when voting rights are again under threat, the historian Gary May’s new book on the Voting Rights Act, Bending Toward Justice, reminds us of what King said in 1957, at another Lincoln Memorial rally. Without the right to cast a ballot, King said, “I cannot make up my own mind — it is made up for me. I cannot live as a democratic citizen, observing the laws I have helped enact — I can only submit to the edict of others.” Are we turning back to such a time?

King called our country forward on that beautiful day in 1963, but he also called out our failings. He told us there could be no peace without justice, and no justice without struggle. We honor him best by sharing not only his hope but also his impatience and his resolve.

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com.

Photo: Rowland Scherman for USIA, via Wikimedia Commons