By Ben Brody, Bloomberg News (TNS)

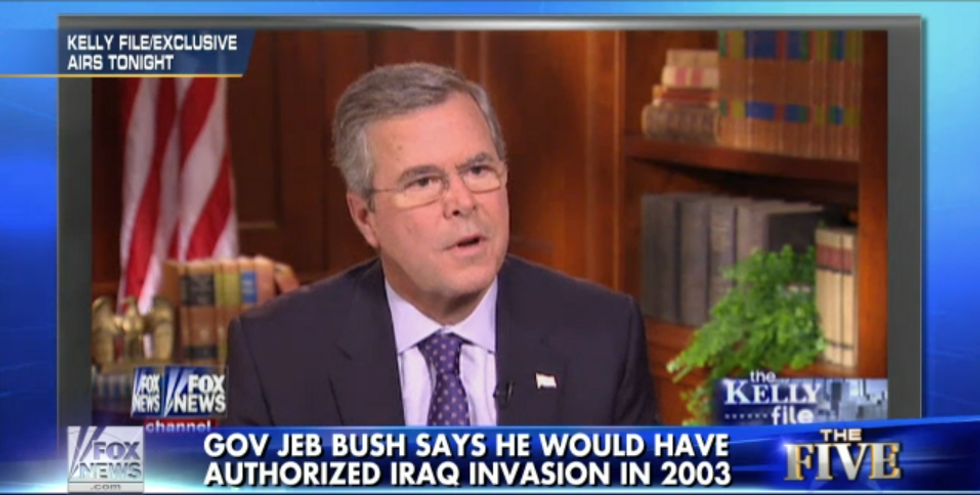

WASHINGTON — On May 10, Fox News released part of an interview that it had landed with former Florida Governor Jeb Bush on its website. In the clip, anchor Megyn Kelly asked Bush whether, “knowing what we know now,” he would have authorized the invasion his brother launched in 2003.

“I would have,” the likely presidential candidate responded, adding, “And so would have almost everybody that was confronted with the intelligence that they got.”

Bush then spent the week shifting his answer on the unpopular war, eventually reversing himself on May 14 and saying that he “would not have gone into Iraq.”

Before the interview even aired on TV, commentators had rehashed many of the tragic lessons the U.S. had learned in Iraq. But many, though not all, of those commentators missed something key: It’s not clear that the invasion was supported by what we knew beforehand.

Between 2004 and 2008, the Senate Intelligence Committee released a series of reports on the war. Based on tens of thousands of pages of documents, several reports detail what the intelligence community and senior Bush administration officials knew prior to their decision to invade Iraq.

The first report, released in July 2004, concluded that “(m)ost of the major key judgments in the Intelligence Community’s October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate,” which summarized what was believed about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, “either overstated, or were not supported by, the underlying intelligence reporting.”

The report blamed these failures mostly on the intelligence community, which sought sources who confirmed pre-existing views and then communicated conclusions to policymakers with far more surety than the evidence warranted.

A second report, however, suggested that the administration could not entirely claim to have been misled by faulty intelligence. That report, from June 2008, found that President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of State Colin Powell, and others used information from the intelligence community in public statements about Iraq but routinely glossed over uncertainties, some of which were significant.

In one of the many statements important in building the case for war, Bush said in his 2002 State of the Union, for instance, that “evidence from intelligence sources, secret communications, and statements by people now in custody reveal that Saddam Hussein aids and protects terrorists, including members of al-Qaida.”

The report found, though, that administration officials’ statements about the link had no basis in analysts’ conclusions, while officials’ repeated insinuations that Iraq would give terrorists WMDs to attack the U.S. actually “were contradicted by the available intelligence.”

The report also addressed the administration’s rosy predictions about postwar Iraq. George W. Bush said in a speech in Cincinnati in October 2002, for instance, that toppling Saddam Hussein would mean “Iraq’s people will be able to share in the progress and prosperity of our time,” while Cheney famously told Meet the Press in March 2003 that the U.S. would “be greeted as liberators.”

Instead, the committee report found that, before the war, the intelligence community actually believed that “(e)stablishing a stable democratic government in postwar Iraq would be a long, difficult and probably turbulent challenge” and that “Iraq was a deeply divided society that likely would engage in violent conflict unless an occupying power prevented it.”

Another committee report added that al-Qaida, which had not benefited from any institutional relationship in before the war, “probably would see an opportunity to accelerate its operation tempo and increase terrorist attacks during and after a US-Iraq war.”

The media often reported the administration’s talking points unchallenged, but the idea that Iraq would be harder to liberate than the president suggested did make it into the public sphere. An Atlantic feature from November 2002 called “The Fifty-First State?” that was written by James Fallows contended that stabilizing Iraq would require an intensive commitment that could last decades and render Iraqis “part of” the U.S.

On May 19 of this year, Fallows weighed in on the Jeb Bush flap, pointing out senior George W. Bush aides started looking seriously at invading Iraq just days after 9/11 and expressing the contention that the administration overstated and misstated evidence because of this resolve.

“The ‘knowing what we know’ question presumes that the Bush administration and the U.S. public … were (unfortunately) pushed toward a decision to invade, because the best-available information at the time indicated that there was an imminent WMD threat,” Fallows wrote. “That view is entirely false.”

Photo: Jeb Bush spoke to Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly about his stance regarding the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Credit: Screenshot via Fox News