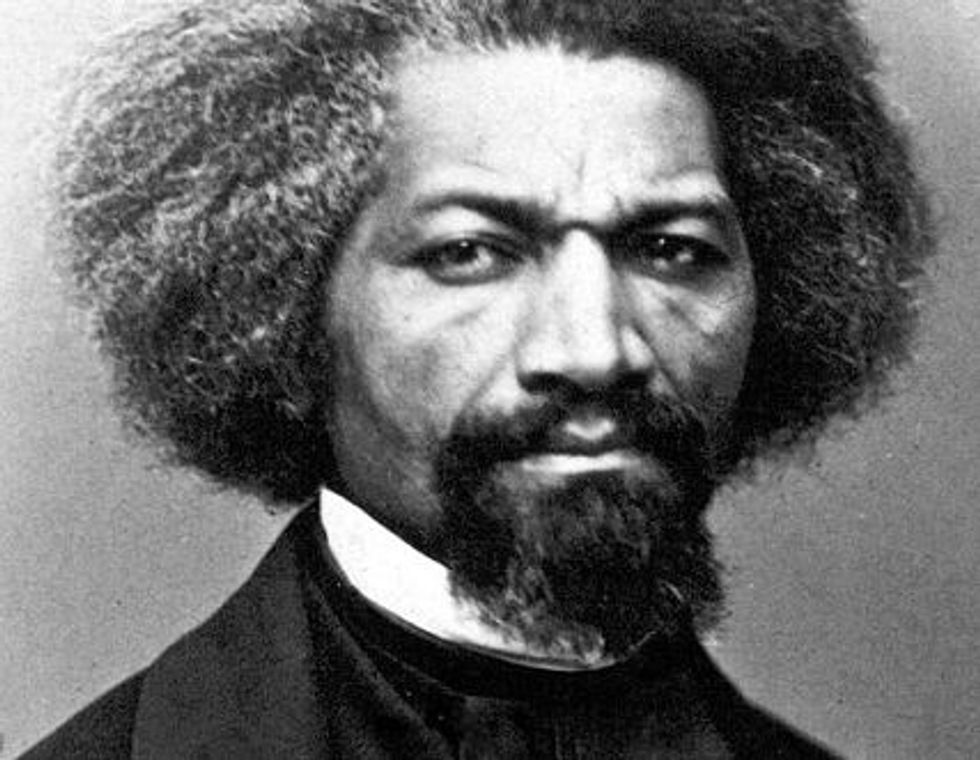

Eighty-seven years ago — when about half of households owned an automobile, women’s suffrage was new and black Americans were still terrorized by lynching, especially in the South — black historian Carter G. Woodson had a simple but powerful idea: Designate a week to celebrate the contributions that black Americans had made to their country. Woodson chose the second week of February to commemorate the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Negro History Week, as it was known, was an important development for its time. Back then, official history barely acknowledged the presence of black Americans, while popular culture actively diminished their humanity. In such a hostile landscape, black Americans desperately needed an acknowledgement of their patriotism, enterprise and ingenuity to foster self-confidence. Knowledge is power.

Decades later, the landscape has changed in such profound ways that Woodson would hardly recognize it. Automobiles are ubiquitous; women voters usually outnumber men in national elections; and a coalition that included unmarried women and black, Latino and Asian-American voters powered the nation’s first black president to re-election last year.

Despite those tectonic, ground-shaking developments, Woodson’s commemoration — now Black History Month — lingers. Yet it is an artifact that, ironically, works to minimize the myriad ways in which black Americans’ accomplishments are part of the national mosaic. In the age of Obama, do we need such a separate and unequal celebration?

Consider: Twenty years from now, will classroom discussions of President Obama be restricted to February? Or does the first black president belong to the broader pantheon of presidents, his legacy discussed alongside those of others? Will a future Barack Obama Presidential Library be a site of commemorations only during the shortest month of the year?

If it is absurd to imagine confining Obama to Black History Month, then it ought to be apparent that it is equally nonsensical to promote the study of Crispus Attucks, Elijah McCoy, Sojourner Truth, Charles Drew, Dorie Miller and the Tuskegee Airmen for only 28 days. The inventions, the patriotism, the industry and the adventurousness of black Americans — soldiers, cowboys, pioneers, engineers — are part and parcel of American history, not some footnote.

Proponents of Black History Month argue that, while that’s true, mainstream (read “white”) America still has not accepted that argument, and the contributions of black Americans are not readily acknowledged. Neither the classroom nor popular culture, they note, has moved much beyond Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King Jr.

Yet continuing to marginalize black Americans with the February set-aside hardly advances the cause. It makes the contributions of a few well-known black men and women seem a historical exception. In thoughtful criticism of Quentin Tarantino’s slave revenge epic Django Unchained, historian William Jelani Cobb argues that the movie’s biggest flaw lies in the message that its title character is the rare enslaved black man who rose up against his oppressors. In fact, white plantation owners lived in fear of slave rebellions, large and small. (Ever heard of Nat Turner?)

Similarly, Black History Month places our history outside its context, separating it from the larger American story. The truth is that blacks participated in every major development in U.S. history. From the bloody Boston Massacre, to the settling of the West, to the World Wars and the labor movement, to the exploration of space, black Americans have been present as footsoldiers and leaders. In other words, black history is American history.

We Americans, regardless of color, are not particularly well versed in our nation’s story; if “black history” isn’t well understood, neither is “white history.” There have long been roiling battles between the realists and the mythmakers who would whitewash the carnage that followed Columbus’ “discovery,” tidy up the Founders and ignore the systemic oppression visited upon blacks for generations.

As for popular culture, it may be an even harder re-write since moviegoers want romance, not the hard truth. That’s why I give Tarantino some credit for Django Unchained, ahistorical though it may be. It gets the cruelty of slavery right. And it wasn’t released during Black History Month.

(Cynthia Tucker, winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, is a visiting professor at the University of Georgia. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com.)