Over his 22 years of post-mayoral life, Ed Koch proved he could transcend not only an electoral loss but a moral mistake, and rise, like his city, to a brighter morning.

The shorthand on the top of every Ed Koch movie review was a plus or minus sign. This master of the soundbite always got right to the point. His life, all 88 years of it, gets a plus sign now, even from one of his most relentless critics. We know he had 12 years at Gracie without a dull moment, and a grand post-mayoral schtick of more than 22 years. His post-death life, judging by the media clamor today, may last nearly as long. He died the day Neil Barsky’s documentary classic, Koch, is premiering across the country, once again proving he has the timing of a box office king.

His own account of how he became a movie critic is pure Koch. Called by Tom Allon, the editor of a Manhattan weekly who is running for mayor himself this year, and offered $50 per review, Koch replied: “I wouldn’t cross the street for $50.” How much do you want, asked Allon. “Two hundred and fifty,” Koch insisted. We’re a small paper, said Allon, saying he couldn’t afford that. “Call me back when you get bigger,” said Koch, and Allon called back a day later, feeling big enough to pay the tab.

He was born to banter. A World War II vet, he loved every form of cojones combat. When it is said, and no one said it more often than he did, that he was New York, what we all meant was that he was its street-smart voice, a daily shot of caffeine that stirred our subway and sidewalk blood. I dubbed him Mayor Mouth decades ago, and he relished the title. He could’ve charged for his shirtsleeve press conferences and still packed the house, always making sure that he called on his nemesis reporters first, including me. There or anywhere else, whatever popped into his head emerged instantly from his mouth.

When he had his 1991 heart attack, he was conscious during a difficult pacemaker operation and had a silent conversation with God. “I was doing all the talking,” he recalled, a premonition about what’s happening somewhere today. He was thrilled then that two years out of office, the news that he collapsed “traveled faster” than the ambulance, just as he’d publicly marveled when he had his 1988 stroke and a doctor declared he had the brain of a 28-year-old.

Much of the commentary on him now is celebrity chatter, because he was, in our memory, more a character on our living room couches than a municipal mechanic or manager. But he did in fact do things that will forever matter in the life of the city. As deserved as the racial criticism of him was at the time, it is the ultimate irony that the monument to him is the not the renamed Queensborough Bridge, but the 365,000 housing units that have been built or rehabbed with city capital dollars and transformed the city’s poorest neighborhoods since Koch launched that effort. Though no mayor before him had spent a dollar restoring the housing stock (it was a federal gig), none since has dared walk away from the unique financial commitment Koch made to our neighborhoods and we have now spent, collectively, $13.5 billion converting every part of the city into a home. When he lost to the city’s first black mayor in 1989, he didn’t carry one of the neighborhoods he and his imitating successors rebuilt.

His greatest achievement was directly linked to his greatest failing. He had excused his own racial rhetoric by declaring that most blacks were anti-Semitic, as if nothing he could say or do would make him okay in their eyes, a charge that hardly requires rebuttal, but one that Mike Bloomberg has certainly put the lie to, both in polls and at the polls. If they don’t like me, it’s their fault, was all Koch would allow himself to see, regardless of cause. All these years later, this stain makes it impossible to write an obit of him without conceding that you are looking through a white lens.

The $5 billion, 10-year housing plan he announced in 1985 was also a response to a scandal that so shook Koch he seriously contemplated suicide, an unimaginable short-circuiting of the life he led since it. He died without ever really accepting his own responsibility for the worst municipal scandal in the modern history of New York. He accurately described himself as innocent of all criminal charges. He would no sooner take a penny than he would take a punch.

All he cared about, and sadly all he had in the end, was the public artifice he’d constructed; a celebrity mayor stretched across the skyline. To get there and stay there, he handed off pieces of his administration to the party bosses that ruled the still formidable outer borough Democratic machines, all of whom were mirror images of the Manhattan boss, Carmine DeSapio, that reformer Koch had toppled in the Village at the start of his career. No one knew better than Koch that all these bosses cared about were under-the-table deals. Why else would they want to control the city’s leasing agency and the Parking Violations Bureau?

To suggest, as he has, that he knew nothing about the cesspools inside his own government is to contradict the core of his celebrity as a quintessential New Yorker. What quintessential New Yorker didn’t know in those days what was driving the predator felons who engulfed wings of his government just ahead of the handcuffs? It is one thing to say he received no prior notice of cash bribes being paid down the hallway, and quite another to say he had no prior notice of the crass clubhouse character of the men he empowered. One followed the other as surely as catastrophe follows a compromise of the soul.

But the scandal did not define him. He was so much more than his weakness. Years of scandal headlines brought him down a peg and, though he never acknowledged it, contributed to his 1989 defeat. But he paid the price that was due. He proved he could transcend not only an electoral loss but a moral mistake, and rise, like his city, to a brighter morning.

Read City Limits for more original coverage of New York City politics and urban issues.

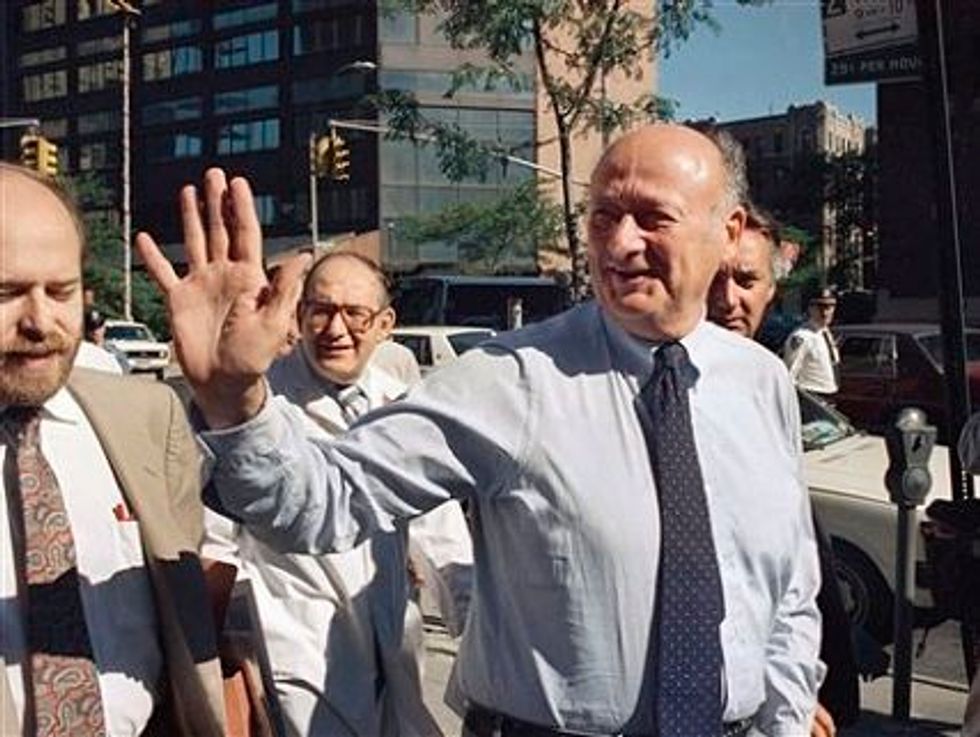

Photo credit: AP/David Bookstaver, file