Reprinted with permission from WashingtonSpectator.

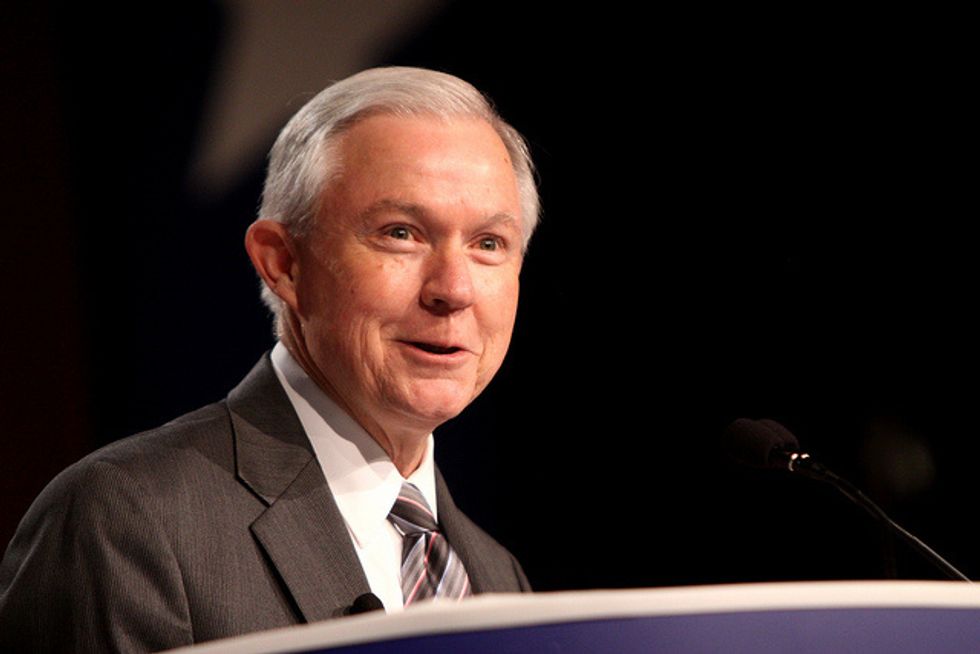

Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III: From commanding the war against immigrants to crusading in defense of the travel ban; from sabotaging the deployment of science on behalf of those wrongly accused to giving urban police departments a free hand to murder blacks; by pioneering new lows in criminalizing dissent and waging jihad against even the medical use of marijuana—and, last but not least, by signing away a decade of bipartisan work to reverse America’s failed, racist mass incarceration policies—the attorney general knows how to get things done. He’s the one who knows how to keep his hands (relatively, so far) clean. As the president who hired him reveals himself as an incompetent, it is no surprise to learn that Sessions was Steve Bannon’s first choice, long before Donald J. Trump was a gleam in the alt-right’s eye. The attorney general is the true white nationalist messiah and the wheelhouse of the Trump Revolution.

So if you’re trying to figure out what makes Jeff Sessions tick, it is worth digging deep. It is Sessions who’ll likely be the one left standing once Bannon, Spicer, Kushner, and all the rest of this Friends and Family administration are gone—probably even after Trump himself oozes into irrelevance. After all, they pretty much work for him, as Sessions made plain in a recent interview with Laura Ingraham. “I’m an admirer of Steve Bannon and the Trump family and they’ve been supportive of what we’re doing. I’ve not felt any pushback against me or anything I’ve done or advocated.”

I began my own excavation by looking back to November 21, 1961, the day the native of tiny Hybart, Alabama, made his first appearance in the newspaper of the big city 85 miles away. At 14, Jeff Sessions had his debut in the Montgomery Advertiser alongside Martha Kay Norman, for being featured in the Wilcox County High School Annual as “Mr. And Miss Junior High.”

I’ve been burrowing into every newspaper database to which I have access and reading up on every time Jeff Sessions was mentioned. You don’t need to get further than his college years for it to prove a useful exercise—even the yearbook stuff. The Dixieland of Jeff Sessions’s youth, the culture that formed him, was first and foremost a world of radical hierarchy—order and domination safeguarded by violence: you know that, just like you know Sessions’s full given name—Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, after the first Confederate president and the Confederate general. But it was also a culture whose cruelty was systematically occluded by a surplus of ritual—obsessively performed public protestations of decency, often subsumed under the banner of “tradition,” or “heritage.” “The lazy, laughing South / With blood on its mouth,” as Langston Hughes once wrote of the land of his birth. Why dive this deep into Jeff Sessions’s past? Because he is working to make it our future.

This was a world where general stores were temples, junior high proms near to religious observances. Which was why a big-city paper would devote six column inches on page 37 to an elaborate cataloging of the contents of a high school yearbook (“Jean Reaves and Douglas Reaves, cutest; Betty Cooper, most feminine…”) from a distant rural county.

Two faces of the cultural coin, the sweet syrup and the sadism, were both on display on that day’s front page, and indeed on every day’s front page. Five of the 11 items were about the coming holidays. “The Christmas sales season in downtown Montgomery will officially begin Thursday night with the lighting of the big tree on the square.” “Give Thanks When Things Seem Darkest, Cleric Asks.” A picture of an adorable three-year-old greedily eyeing turkeys in a store window, captioned “Feast, Prayer, to Highlight Thanksgiving.” (Cute children were a constant on the front pages of Southern newspapers.) A long article on “the 141st annual communication of the Free and Accepted Masons of California.” (Order, hierarchy, “heritage.”)

And the flip side. One article on the bombing of the homes of two Teamster officials in Detroit, unsolved. (Unions: nasty, corrupt monstrosities. The North: a Babylon where law and order was unknown.) Another on the then-notorious case of a Green Bay, Wisconsin, ophthalmologist who murdered his wife and most of his children on the family pleasure boat, the Bluebell; the Advertiser featured the heroic escape of 11-year-old Terri Jo, running a picture of the blond darling being reunited with her favorite, also blond, doll.

And this:

Like millions of others around the nation, Joe Henry Johnson will sit down Tuesday to a Thanksgiving dinner.

But for the 19-year-old Negro slayer, it will be his final holiday meal. … Some 12 hours after dinner, the Negro youth, who raped and killed an elderly white woman, was calm and apparently resigned to his fate, said warden Martin Wiman.

God was in his heaven, and all was right with the world in Montgomery, Alabama, on November 23, 1961.

Another item on that front page feels particularly bizarre; that is, if you didn’t grow up where and when Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III did. It reported, “The head football coaches of Alabama and Auburn say the $10 million the state proposes to spend on a new prison system will be worth every cent of it. If for no other reason, said Coaches Paul (Bear) Bryant of Alabama and Ralph (Shut) Jordan at Auburn, the chance of rehabilitating teen-age prisoners will justify the expense. Bryant and Jordan, along with Auburn Athletic Director Jeff Beard, endorsed the bond issue in letters to state prison director Frank Lee.…”

These tough but fair patriarchs were not just sports icons but cultural and political leaders. Football was the South’s ne plus ultra ritualization of order, hierarchy, and violence. Which was why, when 15-year-old Jeff Sessions made the roster as a linebacker in Camden, Alabama (population in the 1960 census: 1,211), that was important enough to make the Advertiser, too.

On November 22, 1962—shortly before Thanksgiving—the front page featured a picture of a little kid holding up a turkey (for his father, who wielded the ax), and this news from one state over:

OXFORD, Miss. (AP) — Chief U.S. Marshal James D. McShane gave himself up for arrest here Wednesday on charges of inciting to riot and breach of the peace growing out of the University of Mississippi desegregation riots.…The Lafayette County grand jury, following an investigation of the bloody desegregation riot on the Old Miss campus the night of Sept. 30, returned two indictments in the case…. McShane was in charge of a team of about 300 federal marshals accompanying James H. Meredith, a Negro, onto the University campus.

The marshals, after taking Meredith to a dormitory, set up a circle of men, standing shoulder to shoulder, around the Lyceum building, where the registrar’s office is located.

A crowd gathered and violence broke out. During the night of rioting, two persons were killed, and scores more—students, marshals, and others—were injured.

You read that right: when the local grand jury met to hear the local prosecutor’s arguments about how best to preserve law and order in the face of the riot, the person they agreed to indict for causing it was the man the federal government sent to take charge of protecting James Meredith from a bloodthirsty mob. Which is also bizarre, if you didn’t grow up where and when Jeff Sessions did, with a father like his—who once allowed, when his son was up for a federal judgeship in 1986 and defending himself against witnesses who remembered him calling them “nigger,” and calling the NAACP and National Council of Churches “un-American” for shoving “civil rights down the throats of people trying to solve problems on their own,” that, yes, he, Jefferson Beauregard Jr., believed in “the separation of the races.”

His dad said that shouldn’t be held against his son, Jefferson Beauregard III. But evidence concerning his upbringing is clarifying. By Jefferson’s next appearance in the papers, it’s 1965, and he’s beginning his apprenticeship in preserving the lazy, laughing South with blood on its mouth just as he experienced it growing up—preparing for a life’s work imposing its perversions nationwide.

Outside, the Sixties were in full swing. Inside his world, the establishment was standing athwart them, yelling “Stop!” On July 14, he was the pallbearer at the funeral of a friend. President Johnson was expanding draft calls—but the Advertiser’s front page gave more room to a report by its “women’s editor” on the fall fashion lines, with fabrics “more luxurious than ever before,” and gave visual confirmation that the corn in Mrs. Susan Martin’s front-yard patch was so high she couldn’t reach the top with a yardstick.

April 18, 1966, when Sessions was elected vice president of the Young Republicans Club at Huntingdon College, a gubernatorial candidate was also warmly profiled who “wants to convert state government to the methods of a business corporation.” And the U.S. Air Force made its “closest raid yet to the North Vietnamese capital.” For in the Advertiser, while the Vietnam War might be expanding, it was also going triumphantly.

On May 3, 1967, news that Sessions was among those “tapped for membership in the International Relations Club at Huntingdon College” made page 2. Page 1: “City Negro Population Decreasing,” “Marines Take Hill 881; Planes Blast MIGs,” “Card-Burning Law Going to Top Court”—and a unique dispatch, “Seminarians Turn Table on Pickets,” featuring the Rev. Carl McIntire, a whackadoodle syndicated radio fundamentalist infamous for demanding a first nuclear strike against the Soviet Union, but still a hero to the Advertiser’s editors for confronting an anti-war demonstration at a conference calling for unity among Christian denominations in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The ecumenists were met with “robust spirituals,” prayers for their eternal souls, and McIntire’s protest sign, which read: THE WORLD CHURCH—A TOWER OF BABBLE.

On August 20, 1967, when Sessions was helping plan a student government retreat as junior class president, the front page featured “Marine Riot-Control Gas Grenade Flushes Out Four Viet Cong Suspects” (what were those skeptics of Vietnam as an “unwinnable” war even talking about?); a photo captioned “U.S. paratrooper carries injured North Vietnamese soldier” (and Martin Luther King called a decent nation like ours “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today”!)— and Yankee lawlessness, that reliable evergreen, datelined “SAINT CLOUDY, Minn. (sic)”: “Man Admits Killing Wife, Leaving Youngsters to Die.”

Sessions made the front page for the first time in one of those “all is right with the world” photo features. He starred gallantly helping two identically dressed twin girls with their luggage on the first day of school in 1967. Below that, one read of the “closest strike yet to the center of North Vietnam’s major port” by U.S. jets. Beside that was the day’s lead article, on a proposed “teacher choice” law from Governor Lurleen Wallace (installed in office by her segregationist husband, George Wallace, because Alabama law did not permit a governor to serve two consecutive terms), “which permits parents to choose by majority vote the race of their children’s teachers.” (Below that, a dispatch from the hellholes above the Mason-Dixon Line; “Teacher Strikes Continue in New York and Detroit.”

In March of 1968, Sessions was elected student government president (“War Deaths Nearly Triple Same Period’s Rate in ’67”); in August, he’s helping lead the student government retreat (“Gov. Lester Maddox of Georgia, claiming growing delegate support and voter appeal throughout the country,”—a fantasy, though one Alabamians seemed eager to maintain—“announced his candidacy Saturday for the Democratic presidential nomination”); in October, the student body president is featured as head of the youth division of the campaign for Alabama’s Republican candidate for Senate, Perry Hooper.

His picture in all three articles is the same. All the pictures of young people are the same: closely razored hair and neat suits for the men, tight helmets of hair on the women—it’s 1958 forever. In one sense, however, he was ahead of his time. Republicans were still rare in Alabama. On the front page that day, Richard Nixon’s most prominent Southern supporter, Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, the former Democrat who ran a third-party segregationist “Dixiecrat” campaign for president in 1948 and who switched to the Republicans in 1964, claims his support for Nixon has brought him death threats. That fall, Sessions’s candidate, Perry Hooper, won only 22 percent of the vote.

It soon became plain that for a young tribune of the lazy, laughing South with blood on its mouth, the GOP was the place to be.

At the Republican convention in 1968, Thurmond agreed not to break from Nixon for Ronald Reagan, in exchange for Nixon’s pledge to do all he could to keep Southern schools segregated. The following September, Sessions, a newly matriculated student at the University of Alabama Law School (his acceptance there had been reported in July), was groomsman at a wedding on a day the Advertiser’s front page reported a Nixon official’s fervent defense of the administration’s civil rights record—“anxious to counter criticism that followed his request in a federal court to give 30 Mississippi school districts additional time to implement court-ordered desegregation.”

It is as crystalline an example as I’ve ever seen of what Nixon Attorney General John Mitchell promised at the beginning of the administration: “Watch what we do, not what we say.” Yes, young Jefferson Sessions was in the right place. In 1971, he was elected chairman of the student division of the Alabama Young Republicans. In 1972, he was picked as a presidential elector for Nixon. The September 2, 1972, Advertiser printed the parties’ presidential ballots. There was the “Democratic Party,” full stop, whose emblem read “For the right.” That was the local version of the party, whose lever you pulled if you were a voter who wished to honor the party of your fathers and grandfathers without defiling your franchise with support for the alien, “national” body that picked the anti-American quisling Yankee George McGovern as its presidential nominee. But there was also the “National Democratic Party of Alabama.” That Democratic formation was a predominantly black organization, whose ticket included McGovern but excluded George C. Wallace.

By 1972, the party of Jefferson was at war with itself in the South, between black and white; future and past; Washington, D.C., and Montgomery; George McGovern and George C. Wallace. The party of Jefferson Sessions, on the other hand, suffered no such confusion; it knew where it stood. Want to vote for Richard Nixon? Just pull the lever with the emblem that simply read: America First: G.O.P.

Rick Perlstein is The Washington Spectator’s national correspondent.

Trump Cabinet Nominee Withdraws Over (Sane) January 6 Comments