How Tillerson Created The (False) Impression He Supports Climate Action

Donald Trump’s unorthodox selection of ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson for secretary of state touched off a flurry of stories about how an engineer from humble beginnings rose through company ranks to become one of the world’s most powerful corporate titans, negotiating with potentates and presidents in dozens of countries spanning the globe.

Much of the coverage has focused on Tillerson’s chummy relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, which has raised eyebrows among Democrats and Republicans alike, including Sens. Lindsey Graham, John McCain and Marco Rubio. Tillerson’s bromance with the Russian strongman, however, has largely overshadowed another major area of concern: ExxonMobil’s leading role in promoting climate science denial and blocking government efforts to address global warming.

Instead of exploring those issues, many news organizations have accepted at face value statements Tillerson and his lieutenants have made about company climate policy. A closer look, however, shows that while Tillerson may talk the talk, when it comes to walking, he’s heading in the wrong direction.

As a number of reporters have noted, Tillerson — unlike his crusty predecessor Lee Raymond — acknowledges that climate change is a problem. “At ExxonMobil,” Tillerson said in May at a conference in Washington, D.C., “we share the view that the risks of climate change are serious and warrant thoughtful action.”

That sounds promising, right? But Tillerson followed that statement by noting that more than a billion people around the world lack access to electricity, living in what he called a state of “energy poverty.” Cutting back on fossil fuels, Tillerson said, would condemn them to a life of deprivation. His solution: more fossil fuels, especially natural gas. As he has said on other occasions when addressing the same topic: “What good is it to save the planet if humanity suffers?”

Tillerson also routinely disparages well-established climate models, insisting they are inaccurate, and recommends societies learn how to adapt to sea level rise and other consequences of global warming instead of trying to reduce carbon emissions.

“Changes to weather patterns that move crop production areas around — we’ll adapt to that,” he said during a talk at the Council of Foreign Relations in June 2012. “It’s an engineering problem and it has engineering solutions. …The fear factor that people want to throw out there to say we just have to stop this [carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels], I do not accept.”

Tillerson reiterated his disdain for climate science before a much larger audience the following March. During an hour-long interview on PBS’ Charlie Rose, he emphasized uncertainty — exactly what ExxonMobil did after its own scientists warned upper management in the late 1970s about the potential for climate catastrophe. “We have continued to study this issue for decades,” he told Rose. “… With all of that [new data, better models, and more competent analysis], though, the facts remain there are uncertainties around the climate, climate change, why it’s changing, what the principal drivers of climate change are.”

Social scientists call that “manufacturing doubt.” That’s just what the tobacco industry did to stave off tighter government controls on its product despite the fact the science linking smoking to cancer and other diseases was conclusive — just as climate science is today.

Stories about Tillerson’s nomination in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and other publications have uncritically repeated ExxonMobil’s hollow assertion that it endorses a carbon tax. As I have previously pointed out, Tillerson first claimed to back a revenue-neutral carbon tax in 2009 in a cynical attempt to derail congressional approval of a rival approach — a market-based, cap-and-trade system — that was gaining ground at the time. In fact, a cap-and-trade bill did pass narrowly in the House, only to die later in the Senate.

Not only was Tillerson undoubtedly aware back then that a carbon tax had virtually no political support, since 2009 ExxonMobil’s friends on Capitol Hill have made sure that no carbon tax bill will ever see the light of day. There have been a handful of nonbinding carbon tax resolutions in recent years, however, and the overwhelming majority of ExxonMobil-funded senators and representatives consistently voteagainst it. Meanwhile, the company has ignored members of Congress who have actually sponsored carbon tax legislation. Earlier this year, for instance, Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse and Brian Schatz — who get no financial support from ExxonMobil — introduced a revenue-neutral carbon tax bill. Did they hear from the company? No.

“Regarding ExxonMobil’s alleged seven years of support for a carbon fee, we’ve seen no meaningful evidence of that,” the senators said in a letter they sent to the company in August. “None of the top executives that make up ExxonMobil’s management team has expressed interest in meeting with any of us to discuss the Whitehouse-Schatz proposal or any carbon fee legislation.”

In an otherwise critical editorial on Trump’s pick for secretary of state, The New York Times applauded Tillerson for pulling the plug on climate science denier groups. “On a positive note,” the paper of record opined, “Mr. Tillerson has reversed Exxon Mobil’s long history of funding right-wing groups that denied the threat of global warming, and he could perhaps persuade Mr. Trump not to pull out of the landmark Paris agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

In fact, Tillerson did not completely pull that plug. Despite company denials, ExxonMobil has continued to spend millions of dollars on denier groups since Tillerson took over the tiller in 2006. Outed by a 2007 report by the Union of Concerned Scientists, the company spent more than $18.6 million from 1998 — a year before it merged with Mobil — through 2005 on more than 40 think tanks and advocacy organizations. The company did drop some deniers from its roster in response to negative publicity, but from 2006 through 2015, it spent another $14.3 million on its climate disinformation network. Sixteen groups received ExxonMobil funding last year, and 10 of them — including the American Enterprise Institute, American Legislative Exchange Council, Federalist Society and Hoover Institution — were listed in the 2007 UCS report.

As for the Times‘ hope that Tillerson, as secretary of state, could persuade Trump to uphold the Paris climate accord, it’s not clear he would try. After all, his company stands to profit handsomely if it fails.

It is true that ExxonMobil endorsed the agreement, at least on paper. A close reading of the company’s statement of support, however, suggests that it hinges on whether its own agenda is satisfied.

After calling the accord “an important step forward by world governments” and insisting that ExxonMobil “has a constructive role to play in developing solutions,” the statement urges policymakers to reduce carbon emissions “at the lowest cost to society, keeping in mind that access to affordable and reliable energy is critical to economic growth and improved standards of living worldwide.”

Ensuring worldwide access to energy is a not-so-veiled reference to Tillerson’s pet energy poverty argument, and as we know, his solution for the developing world is to buy more of what his company sells.

The statement’s conclusion, meanwhile, is especially ironic. It declares the best policy option to meet the challenges of curbing carbon and providing energy to all is — you guessed it — a carbon tax, which the company has been working overtime to make sure never happens.

When senators begin to weigh the pros and cons of Tillerson as the nation’s top diplomat a few weeks from now, they need to take into account the fact that he has spent his entire professional career at a corporation whose foreign policy is not only often at odds with U.S. interests, but one that has done more than any other oil company over the last two decades to spread climate science disinformation and prevent urgently needed government action. If they take the confirmation process seriously — and consider the harm Tillerson has inflicted on the planet to protect ExxonMobil’s bottom line — they will reject him. Let him retire next year with his $69.5 million pension and $218 million in company stock. He’ll be fine — and hopefully won’t be able to do any more damage.

Elliott Negin is a senior writer at the Union of Concerned Scientists. His articles have appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, Columbia Journalism Review, The Hill and many other publications.

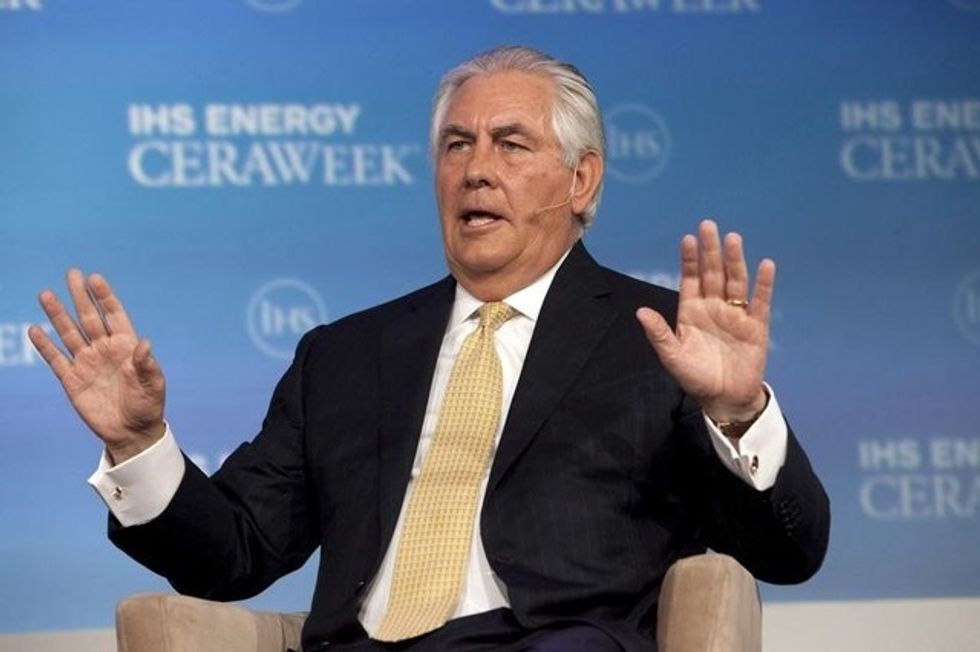

IMAGE: ExxonMobil Chairman and CEO Rex Tillerson speaks at an energy conference in Houston, Texas April 21, 2015. REUTERS/Daniel Kramer/File Photo