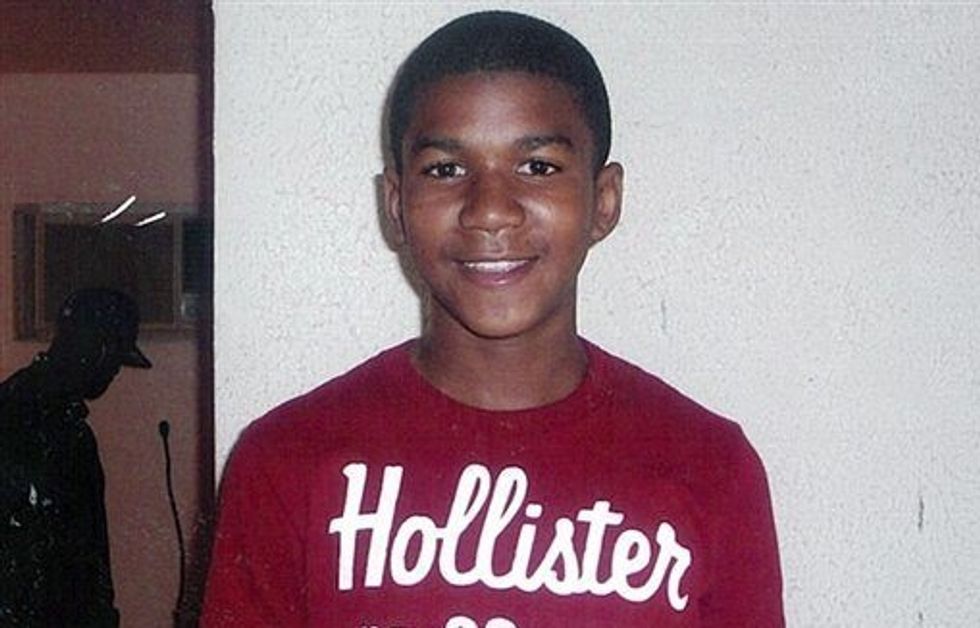

A few words on the innocence of Trayvon Martin.

The very idea will outrage certain people. Experience says the notion of Trayvon Martin being innocent will offend them deeply.

But they can get over it. Or not.

Because it is five years now since Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin’s unarmed son died. Five years since he was killed in Sanford, Florida by a neighborhood watchman who dubbed him, on sight, a “f—— punk” and one of “these a–holes.”

Five years. And there are things that need saying. His divorced parents say much of it in Rest In Power, their new book about the tragedy.

“My son had been intensely alive!” writes Martin. “My son had been a life force, a teenager who had hopes and dreams and so much love. But in death, he became a figure we could only see through the dark mirror of evidence and testimony, a cursed single night when our son and all that life inside him was reduced to a stranger, a black kid in a hoodie, a young man in the shadows. A suspect.”

George Zimmerman was the first to make that reduction when he stalked Trayvon through a gated community despite a police dispatcher advising him to stay with his car. Then the police did it, testing the shooting victim for drugs and alcohol while telling his killer to “go home and get some rest.” Then the jury did it when they set Zimmerman free.

Much of America did it, too. One reader wrote — without a shred of evidence — that Trayvon was “casing” houses when he was shot. This was a boy walking back from 7-Eleven to watch a basketball game at his father’s girlfriend’s house.

Another person, upset that family photos made Trayvon look too young and, well … innocent, forwarded a chain email showing a tough-looking man, with beard and mustache, tats on his hands and face, insisting, “This is the real Trayvon.” It was actually the real Jayceon “Game” Taylor, a then-32 year old rapper.

Supplied with a death scene image of Trayvon — darker skin than Taylor, younger, slimmer, no facial hair, no visible tats — the woman was unmoved. “They’re both Trayvon,” she insisted.

Because Trayvon could not, at all costs, be innocent. The very idea was a threat.

So people embraced absurdities. Like a 140-pound boy jumping a man 12 years older and 50 pounds heavier. Like the boy hitting the man 25 or 30 times and bashing his head against concrete, though Zimmerman’s “injuries” amounted to a bloody nose and scratches on the back of his head that needed no stitches. Like Trayvon, shot point blank in the heart, dying like a villain in some 1950s western, groaning, “You got me.”

They seized upon his suspension from school. For them, it proved not that he was an ordinary boy who needed — and was receiving — the guidance of two loving parents. No, it proved he was not, could never be, innocent. Trayvon was no angel, they would announce triumphantly.

But why did he have to be? And why was there no similar requirement of the killer, who had been arrested once for scuffling with a police officer and had been the subject of a domestic-violence restraining order? The answer is too obvious for speaking.

Five years ago, a black boy was shot for nothing. And many Americans made him a blank screen upon which they projected their racialized stereotypes and fears.

They could not allow him to be a harmless child walking home. No, they needed his guilt.

They knew what it proved if Trayvon Martin was innocent.

Namely, that America was anything but.