Reprinted with permission from AlterNet.

In the first few days after Donald Trump’s election, the Southern Poverty Law Center issued a report showing a shocking rise in what it called “bias-related” crimes. The report revealed spikes in anti-immigrant, anti-black, anti-white, anti-Muslim, and anti-LGBT incidents around the country.

The outpouring of hate has spared no one. Every day we see new evidence that Trump and the reaction to his election have emboldened racists and hateful bullies on every corner. They’ve come out into the daylight to see if anyone is going to stop them, and Trump only continues to egg them on.

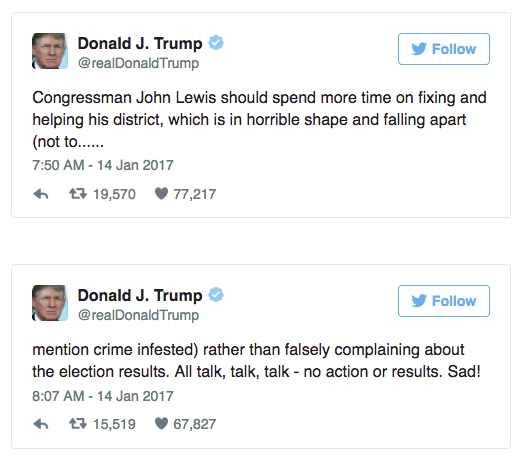

One thing that has helped curb hateful, racist crime in the past 50 years of American history is when communities work with institutions like the Department of Justice. But if Trump—the president-elect who attacked civil rights hero John Lewis on Martin Luther King weekend—gets what he wants, the person in charge of the Department of Justice will be Jeff Sessions. This is a chilling thought for anyone who cares about civil rights.

Sessions has a history of racist, reactionary behavior in his personal life that has already prevented him from becoming a federal judge, and he has advocated for racist policy in his professional life. Sessions says the NAACP and the ACLU are groups that “shove civil rights down the throats of people trying to solve problems on their own.”

This is especially troubling because the Department of Justice, the NAACP, and the ACLU have been in the past what stands between vulnerable communities and mob justice.

In 1961, for example, a group of people wanted to ride a bus; a racist mob didn’t want them to. In Parting the Waters, Taylor Branch explains what happened next:

“The Greyhound escaped down Highway 78 at a high rate of speed, spurred on by reports from the back that the mob was in hot pursuit. About fifty cars, containing as many as two hundred men, soon were stretched out behind them as the Freedom Riders headed for Birmingham. Not far outside Anniston, the bus began to list to one side, and the driver realized that some of the slashed tires were going flat. Helpless, he pulled the bus off the highway, shut down the engine, and scampered off into the countryside. The sounds of slamming doors and shouts from the converging posse were amplified by the quiet of the bus.

“This time the mob used bricks and a heavy ax to smash the bus windows one by one, sending shards of glass flying among the passengers inside. The attackers ripped open the luggage compartment and battered the exterior again with pipes, while a group of them tried to force open the door. Finally someone threw a firebomb through the gaping hole in the back window. As flames ran along the floor, some of the seats caught fire and the bus began to fill with black, acrid smoke.”

This was the first Freedom Ride, conceived in part by Rep. John Lewis—the man Trump attacked for being “all talk, no action”—and carried out by courageous activists and organizers who were willing to risk their lives for justice. To sit where they wished was a civil right afforded them by the Supreme Court. (In case you wondered, in 1961, Donald Trump was dodging the draft and abetting hazing at his posh academy.)

Robert Kennedy was Attorney General then. The reports of this incident and those that followed spurred Kennedy’s Department of Justice to take action, to make sure there were consequences for mobs that broke the law. Kennedy took on the mantle of protecting federally protected civil rights, ultimately playing an instrumental role in the eventual passage and legacy of enforcement for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Without the Justice Department, there would only have been more mob justice.

These victories did not stop racism in America, but they helped alleviate suffering and empower people to participate in democracy. It was progress toward a more equitable and just America.

Trump and Sessions are part of a right-wing wave dedicated to rolling back civil rights protections. The idea of what can happen without the protections of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act does not keep them up at night.

Ripe for whitelash

In Patrick Phillips’ extraordinary book Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America, he describes the conditions of post-Civil War Forsyth County, 40 miles north of Atlanta, in 1912, before the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the courage of the Freedom Riders. He describes conditions in which the status of poor white men had become increasingly precarious:

“All over north Georgia, the war had left devastation in its wake, and the decades after the surrender at Appomattox brought a crippling shortage of credit to a region struggling to recover….In the wake of emancipation, this meant [white farmers] competing not just with other white renters but with a whole new class of free blacks, who many owners saw as more appealing tenants and employees than poor whites. In a Jim Crow South where African Americans were disenfranchised at the polls and powerless in the courts, landowners could hire and rent to poor blacks, secure in the knowledge that if there was ever a dispute over rent payments, crop shares, or wages, the white man’s word was sure to prevail.”

Forsyth had a destabilized white working-class with a disenfranchised minority, all in the midst of rapid, foundational change in the national economy. The uneasy region was ripe for a “whitelash.” And once provoked, white Forsyth residents succumbed swiftly and horrifically to mob violence.

That fall, after the still-unsolved murder of a Forsyth teenager, white vigilantes rose up. In just a few short weeks, they used the murder as an excuse to lynch, terrorize and ultimately drive the entire black community out of the county. Thousands of people, many of whom had been there generations, were gone nearly overnight.

The racist mob created a de-facto white separatist colony inside the United States—one that lasted for decades.

Phillips writes,

“The purge was so successful that within weeks there was no one left for the mobs to terrorize, and whites who had either taken part in the raids or simply stood aside as they passed now settled back into the rhythms of farm life….Generation after generation, Forsyth County remained ‘all white,’ even as the Great War, the Spanish influenza, World War II, and the civil rights movement came and went, and as kudzu crept over the remains of black Forsyth.”

Readers could take some comfort in thinking this was a shameful event lost to the past that could never happen again in our enlightened 21st century, but that would be a mistake. The worst of our society need little encouragement to act on their violent urges. The SPLC has given us over 1,000 reasons to think it can happen here. It can happen now.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Even if we don’t have a strong Department of Justice, there are still ways to stop mob violence. Back in 1912, the violent racial hysteria had a chance to jump across the Chattahoochee River from Forsyth County into nearby Hall County, with the city of Gainesville at its center, but it didn’t. Many of the black citizens of Forsyth fled across the river into Gainesville, where the conditions were ripe for the same response from the white residents. It was also a North Georgia county in the midst of economic turmoil and change, but despite a few isolated incidents, the racial cleansing did not occur there. Why?

For one reason, the white residents of Hall County stood in solidarity with the black residents against the mob, Phillips writes. They protected nearby tenant farmers and families when the “night riders” came, and then, crucially, law enforcement stepped in. The police did not aid, abet or enable the mob.

“Though [Hall County Sheriff] Crow was himself a distant cousin to the white girl who had been murdered just across the river, he told reporters that he had every intention of finding and arresting whites who engaged in violence against black families….[the white vigilantes] were tried and convicted for the attack on Hurse, and soon thereafter five more white men went to jail for driving bricklayers off W.A. Gaines’s jobsite in downtown Gainesville.”

The law was still the law in Hall County. There, as in Forsyth, the law forbade the killing and terrorizing of citizens. But in Forsyth County, the law was enforced by Bill Reid, a showboating demagogue who instead of enforcing the law, whipped up passions for political gain. Instead of bringing justice, Reid “presided over an execution with all the excitement of a country fair.”

While the lynch mobs and night riders of Forsyth were enabled and emboldened by a racist showboat and his flunkies, in Hall County the local law enforcement, led by Sheriff Crowe, worked with citizens to stop the terror in its first instances. And they succeeded.

The law is the law

To keep racially charged imaginations from becoming inflamed to the point of mob violence, we need our communities to work together with our institutions to take a strong hand to protect our most vulnerable quickly, as they did in Hall County in 1912 and in Washington, D.C., in the early ’60s.

The law is the law, but Trump and his far-right cohorts want to change the law to render protections for vulnerable communities worthless. Jeff Sessions is a crucial part of that plan. Don’t let them. Find your senators‘ phone numbers and call them to tell them clearly and politely that you don’t want them to confirm Sessions. Do your part to block Trump’s cabinet.

And if Sessions gets through, don’t just hope for the best. Work for justice. Stand with the vulnerable. Don’t let America take one more step back toward mob violence.

Travis Nichols works for Greenpeace. He is the author of Off We Go Into the Wild Blue Yonder and The More You Ignore Me.

IMAGE: Senator Jeff Sessions speaking at the Values Voter Summit in Washington, DC. Flickr/Gage Skidmore