It was one of lawyer Ruth Bader Ginsburg's cases before she took her place on the Supreme Court or in pop culture memes. It is only occasionally mentioned, perhaps because the details illuminated a truth people prefer to look away from, so they can pretend that sort of thing could never happen here.

But something terrible did happen, to a teenager, sterilized in 1965 without fully consenting or understanding the consequences in a program that continued into the 1970s in the state of North Carolina. The girl became a woman whose marriage and life crashed before her story became the basis of a lawsuit Ginsburg filed in federal court that helped expose the state's eugenics program. While North Carolina's was particularly aggressive, other states implemented their own versions, long ago given a thumbs up by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 1927 decision written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

His words — "It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind" — were used as justification for evil.

Reproductive justice, now often seen as shorthand for abortion rights, has also meant the right of a woman or a man to have a child. For those whom authorities deemed unworthy, it was a right denied. That injustice fell on the poor, those called "immoral" on a whim and, disproportionately, the records show, Black, brown and indigenous women and girls, men and boys judged a drain on society.

While North Carolina in 2013 passed a law that gave meager restitution to some of the victims, and those laws are no more, Americans should not be smug about how far we've come.

Headlines out of a Georgia detention center in 2020, and a U.S. president who touts the theory of "good genes" and brags about his own, who rants about the criminality of immigrants and questions the intelligence and résumé of an African American president, are reminders that looking away from the unimaginable is never an option.

Though still under investigation as facts are gathered and patients interviewed, a nurse in the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia had enough doubts to file a whistleblower's complaint. She had questions about unsanitary and unsafe conditions at the facility and about gynecological procedures, including hysterectomies, performed on women, many of whom had language barriers and may not have understood what was being done to them.

The Department of Homeland Security is investigating, immigration officials have said they will no longer send detained women to that doctor, and outraged congressional Democrats are launching an inquiry. But narratives like that one find echoes in detention centers across the country, and anywhere people are incarcerated or at the mercy of those with ideas about who matters and the power to do something about it.

Is this not an occasion for pro-life advocates of every party to raise their voices?

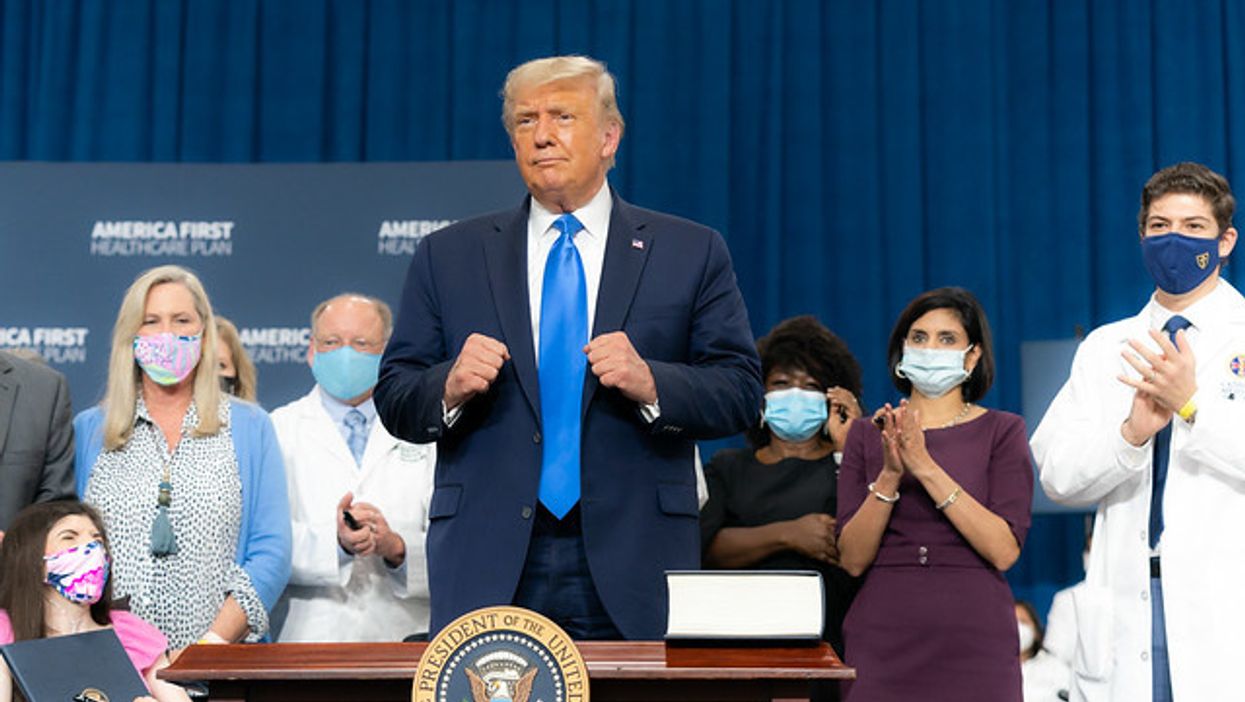

One voice we did hear, loud and clear, was President Donald Trump's at a rally in Minnesota. You would think that a leader's message in a season of marches to call attention to police violence and racial inequities, and in the state where George Floyd was killed, might call for reconciliation. But that would not be this president.

"Good luck, Minnesota. You having a good time with your refugees?" Trump yelled to the crowd at his rally last week. He then went on to attack one particular refugee from Somalia, Democratic Rep. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota. "How the hell did she win the election? How did she win? It's unbelievable," he said.

It would be time to point out the obvious, that Trump's own mother was born in Scotland, and his paternal grandfather in Bavaria. But it's also obvious — from his expletives about certain countries with Black and brown residents — that some countries pass his test and others do not. An influx from Norway would suit him fine, he has said. No doubt his mostly white audience in Minnesota had no trouble understanding.

"You have good genes, you know that, right?" Trump said. "You have good genes. A lot of it is about the genes, isn't it, don't you believe? The racehorse theory. You think we're so different?"

Well, yes, Mr. President, I do.

And when people start talking about human beings as though they were animals, comparing them to horses bred for speed, it has never ended well. Trump and those who find nothing frightening about his rhetoric know little about history, within and outside America's borders.

LISTEN to the first episode of the new podcast Equal Time with Mary C. Curtis

Toxic times

But the teaching of history that tells the whole truth, including the parts no nation would want to repeat, is exactly what the president wants to eliminate with a scheme to make schools teach American exceptionalism, flaws erased. Trump would rather defend memorials devoted to those who fought to tear the Union apart and enslave men, women and children, which shows he flunked his own classes.

We're at a time when the president of all the people is content to divide the nation's coronavirus dead — now past 200,000 — into neat columns of red state and blue state in order to clean up his own dismal pandemic record, and his supporters, among them elected officials, will follow no matter where it leads.

It's not surprising that a toxic refrain about genetic differences among Americans comes and goes with hardly a mention, and reports on possible human rights violations done in our government's name, our name, fight to stay on the front page and in the public's consciousness.

That's why it was so sad and startling to read in a column in The Washington Post that Ginsburg, when she was honored earlier this year, wanted to talk about the case of Nial Ruth Cox, that young Black woman forcibly sterilized in 1965. It's not because Cox got justice. She did not.

Maybe it was to acknowledge the simple and, in 2020, naive notion that some fights are worth having if we are all truly equal.

Mary C. Curtis has worked at The New York Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Charlotte Observer, as national correspondent for Politics Daily, and is a senior facilitator with The OpEd Project. Follow her on Twitter @mcurtisnc3.

CQ Roll Call's new podcast, Equal Time with Mary C Curtis examines policy and politics through the lens of social justice. Please subscribe on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.