By William Douglas, McClatchy Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON — The United States considers Iran a top state sponsor of terrorism, a budding nuclear threat and a meddlesome supporter of President Bashar Assad’s regime in civil war-torn Syria.

But those negatives apparently aren’t enough to prevent Washington from considering calling Iran a potential partner in the battle against a group of al-Qaida-inspired militants who are trying to overtake Iraq.

Washington and the Shiite Muslim-led government in Tehran find themselves on the same side in defending the Shiite-dominated government of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki against the assault from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, a Sunni Muslim insurgent group that’s quickly and violently gained control of swaths of Iraq.

With options limited, the combination of crisis and mutual interest might make possible what many foreign policy experts once thought unthinkable: that the U.S. and Iran, archenemies since the taking of 50 hostages at the U.S. embassy in Tehran in 1979, become partners, frenemies for the sake of Iraq.

“It may be an unholy alliance to some folks, but countries don’t have allies, they have interests,” said retired U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Paul Eaton, a senior adviser at the National Security Network, a liberal research center. “And in this case, Iran is a natural ally of the U.S. They want a stable country around them, and that’s what we want. From a purely realpolitik, Kissinger view of the world, we may have some strange bedfellows here.”

The White House apparently thinks so, too. Deputy Secretary of State William Burns discussed the Iraq situation last week with Iranian officials on the sidelines of a meeting in Vienna on Iran’s nuclear program.

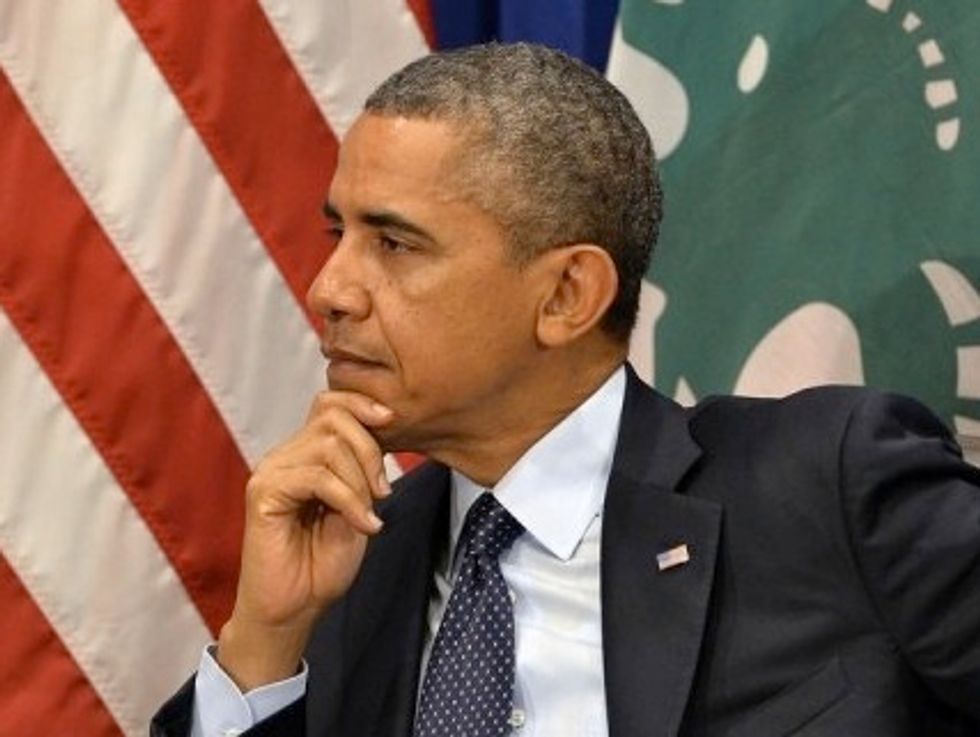

President Barack Obama, in announcing the deployment of 300 advisers to Iraq last week and holding out the possibility of airstrikes, noted that Iran “can play a constructive role if it is helping to send the same message to the Iraqi government that we’re sending, which is that Iraq only holds together … if the interests of Sunni, Shia and Kurds are all respected.”

A potential U.S.-Iran collaborative effort unnerves many in Washington, who worry that the Tehran government will try to extract more favorable terms in the nuclear talks in exchange for its help. House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., last week dismissed the thought of the U.S. teaming up with Iran.

“I’m not one who is interested in working with Iran on this,” Pelosi said. “I think you have to be open about where you get support, but I don’t have the confidence level. Right now, we’re trying to stop Iran from having a nuclear weapon.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said collaborating with Iran made sense because “they know more about what’s going on in Iraq than we do because they have people on the ground.” The New York Times reported that Iran also had embarked on drone surveillance of Iraq.

But Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., Graham’s close friend and fellow hawk, said working with Tehran was out of the question because “the reality is U.S. and Iranian interests do not align in Iraq, and greater Iranian intervention would only make the situation worse.”

Anthony Cordesman, a former senior defense official who’s a strategic analyst for Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, sees little upside for the United States in partnering with Iran and a potential downside if they coordinate on military operations, which the White House rules out.

“The United States can bring air power to bear, but if it brings air power to bear in support of Iranian forces, they’ll be on the ground,” Cordesman said. “They’ll be settling their influence in Iraq. They’ll be at the dividing line of whatever advances or holding position is established between Sunnis and Shiites, and we will have been an enabler and we won’t be present on the ground.”

It’s not as if the U.S. and Iran haven’t dealt with each other before. They shared intelligence in Afghanistan to help oust the Taliban in 2001. Washington and Tehran are now communicating on a higher diplomatic level than they have for years, largely because of the talks to curb Iran’s nuclear program.

But even advocates of cooperation on Iraq say any collaboration must be done with eyes wide open, and with strict parameters. And the union shouldn’t be considered a long-standing partnership with a capital “P.”

“My fear is if you don’t set some red lines with Iran, they’ll pour in troops from the south and there goes Iraq. They’ll do what Russia did with Crimea,” Graham said. “This is not a partnership, a military alliance. This is lines of communication to create red lines and basically exchange operational information to make sure that we don’t do damage, that we don’t hit each other and that we can maximize the effect we have on a common enemy.”

Photo Credit: AFP/Jewel Samad