By Don Lee, Tribune Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON — When Kevin Smith and his partners started a solar energy firm in Santa Monica, California, in 2008, they expected to sell their technology to advanced economies in Europe and the United States.

But much of the action has been in a part of the world Smith initially wrote off: Africa.

Not only are some of SolarReserve’s biggest projects in South Africa, but by year’s end the continent is also likely to generate the bulk of the company’s sales. “We’re now spending a whole lot more time” in Africa, he said, mentioning Ghana, Nigeria and Mozambique, among others.

Sub-Saharan Africa still struggles with political unrest, poverty and disease, including the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa. But the last decade has brought a sea change in its economic performance and perceptions of its future promise. In 2000, Economist magazine dubbed Africa “the hopeless continent.” Today, scholars talk about the “African growth miracle.”

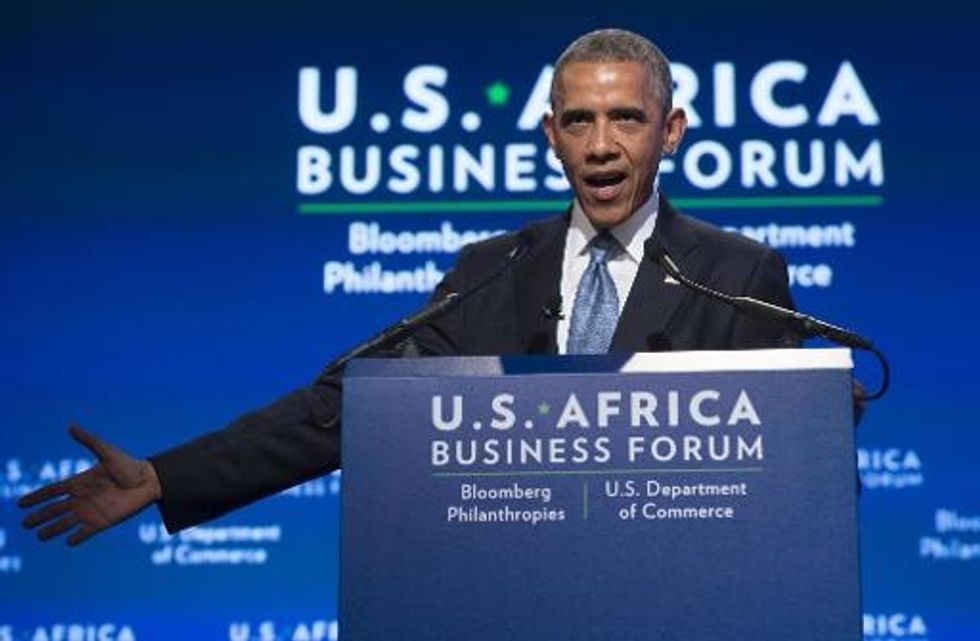

On Tuesday, President Barack Obama acknowledged the transformation, kicking off the first U.S.-Africa leaders summit in Washington by announcing $14 billion in American private investment in Africa for construction, clean energy, banking and information technology. Federal and industry commitments now total about $33 billion.

“I don’t want to just sustain this momentum. I want to up our game,” Obama told a crowd of U.S. and African business leaders, praising the virtues of vibrant markets that offer opportunities “not just for aid, but for trade.”

In many ways, Washington and corporate America are playing catch-up to the Chinese, who for years have held summits with African leaders and have sent armies of workers to cut deals for oil and resources, construct roads and buildings and, more recently, establish shoe and other manufacturing operations.

“It’s clear from being there that we’re significantly behind China, Korea, Germany,” said Robert Blackwell Jr., chief executive of Electronic Knowledge Interchange in Chicago.

At the summit Tuesday, he said his firm recently partnered with an electric company in Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, to provide software and technical systems to better distribute electricity and manage Nigeria’s grid.

“It reminds me of China when I first went there in 2001,” Blackwell said, conceding that it’s far from risk-free. “But I think it’s a huge opportunity.”

China’s footprint in Africa is huge.

“Its presence can be seen and felt almost everywhere one goes in Africa these days,” said Howard French, author of China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa.

SolarReserve’s push in Africa is now focused on staying a beat ahead of the Chinese, who are moving to expand into technology opportunities there.

“We are at risk of having the Chinese capturing market share away from American companies,” Smith said.

China designated Africa as a priority region for expansion in the mid-1990s, French said. Chinese construction companies have been undertaking large state-financed infrastructure projects, sending 200 to 2,000 workers at a time, often on two-year contracts.

Many of those workers are staying on in Africa, he said, “to seek their own fortunes in a new land that they have discovered seems to be wide open for business and full of opportunity.”

To be sure, American commodity firms and corporations such as General Electric and Ford Motor have been in Africa for years, as have U.S. missionaries, relief workers and humanitarian agencies.

But many U.S. companies have been queasy about entering Africa, given its less-developed markets, poor infrastructure, unskilled workforces and especially its violence and war.

Some of Africa’s economic ascendance may be part hype. Obama noted Tuesday that six of the world’s fastest-growing economies are now in Africa, but such growth rates are easier to achieve because the countries are coming from very low baselines.

Nevertheless, there have been clear improvements in areas of governance, health and farming, experts said. As a whole, sub-Saharan Africa’s economy is expected to grow at nearly 6 percent a year on average over the next decade, the fastest of any region in the world.

Companies such as Wal-Mart, Marriott and IBM are expanding in the continent, especially in the biggest and fastest-growing economies — Nigeria, South Africa, Angola and Ethiopia.

Africa’s middle class is budding, and it is entering a so-called demographic sweet spot in which better health and declining fertility rates — which allows more women to have jobs — are boosting Africa’s working-age population, said Margaret McMillan, a Tufts University economics professor who specializes in Africa.

An extensive traveler in the sub-Saharan region, McMillan noted that there’s a Four Seasons in the middle of Serengeti in Tanzania. Africa has the largest penetration of cellphones in the world.

“It’s just amazing,” she said of the capital of Rwanda, a nation once torn by ethnic conflict. “The city is clean. They don’t allow plastic bags.”

So dramatic has been the turnaround that some experts have likened Africa’s growth to the remarkable rise of China and other Asian nations that harnessed manufacturing capabilities to become global export powerhouses.

Africa’s income has long been derived mainly from two sources: commodities and foreign aid. Africa ships all kinds of things farmed or extracted from the land — oil, copper, cotton, coffee. Ethiopia is the largest source of top-notch sheepskin, a key reason the Chinese firm Huajian opened a shoe factory near Addis Ababa.

But over the last decade, much of the economic growth has come from outside the commodity industries, mostly in construction and services such as retail and transportation.

With many countries still lacking adequate roads, rail and electric power, it remains to be seen whether Africa will replicate Asia’s growth model through manufacturing and exports.

For the American economy, Africa represents just a speck of business at the moment.

American exports of goods to Africa totaled about $35 billion last year, largely machinery, vehicles and wheat. That was up from $28 billion in 2010. But it was still a fraction of total U.S. shipments of $1.6 trillion worldwide.

Meanwhile, American imports from Africa have fallen sharply, to $51 billion last year from $87.5 billion in 2010, mainly because of the plunge in U.S. demand for African oil.

Still, for individual American companies, the potential is huge, particularly for those in the energy business. About 70 percent of sub-Saharan Africans live without access to electricity, and more African nations, including Nigeria, recently have moved to open up opportunities to the private sector.

“As soon as they get their hands around the power issue, it’s really going to unlock the economy,” said Blackwell, noting that he is eyeing Tanzania for future business.

SolarReserve, the sun-power storage company, started out gingerly in South Africa by opening a small office in 2011 with one local employee when the Johannesburg government announced a $30 billion renewable energy plan.

Smith, who made his first visit to Africa that year, said he was a little skeptical at first, but the company took the plunge anyway. Launched with seed money from a Los Angeles private equity fund called U.S. Renewables Group, SolarReserve spent several million dollars to buy land and secure permits to be ready to bid for contracts.

So far, it’s been awarded three projects to build and operate conventional solar panel technology valued at $820 million. Its products are based on technology from Rocketdyne in Los Angeles.

Last month, SolarReserve sent one of its two senior vice presidents — and his family — to live and work in Johannesburg. The company has 15 employees there, compared with about 50 in Santa Monica.

The company is awaiting a decision this summer on a bid for a $1 billion project in South Africa to build a thermal energy plant using molten salt technology, similar to a solar power facility that the company is developing in Crescent Dunes, Nev.

“We feel pretty good about it,” he said of the company’s bid, which is competing against Spanish and French companies. The Chinese, he said, are supplying a lot of the equipment and supplies for the renewable energy market, but not the cutting-edge technology — at least not yet.

AFP Photo/Saul Loeb