The Overly Supreme Court -- And Why Democracy Must Rein In Its Excessive Power

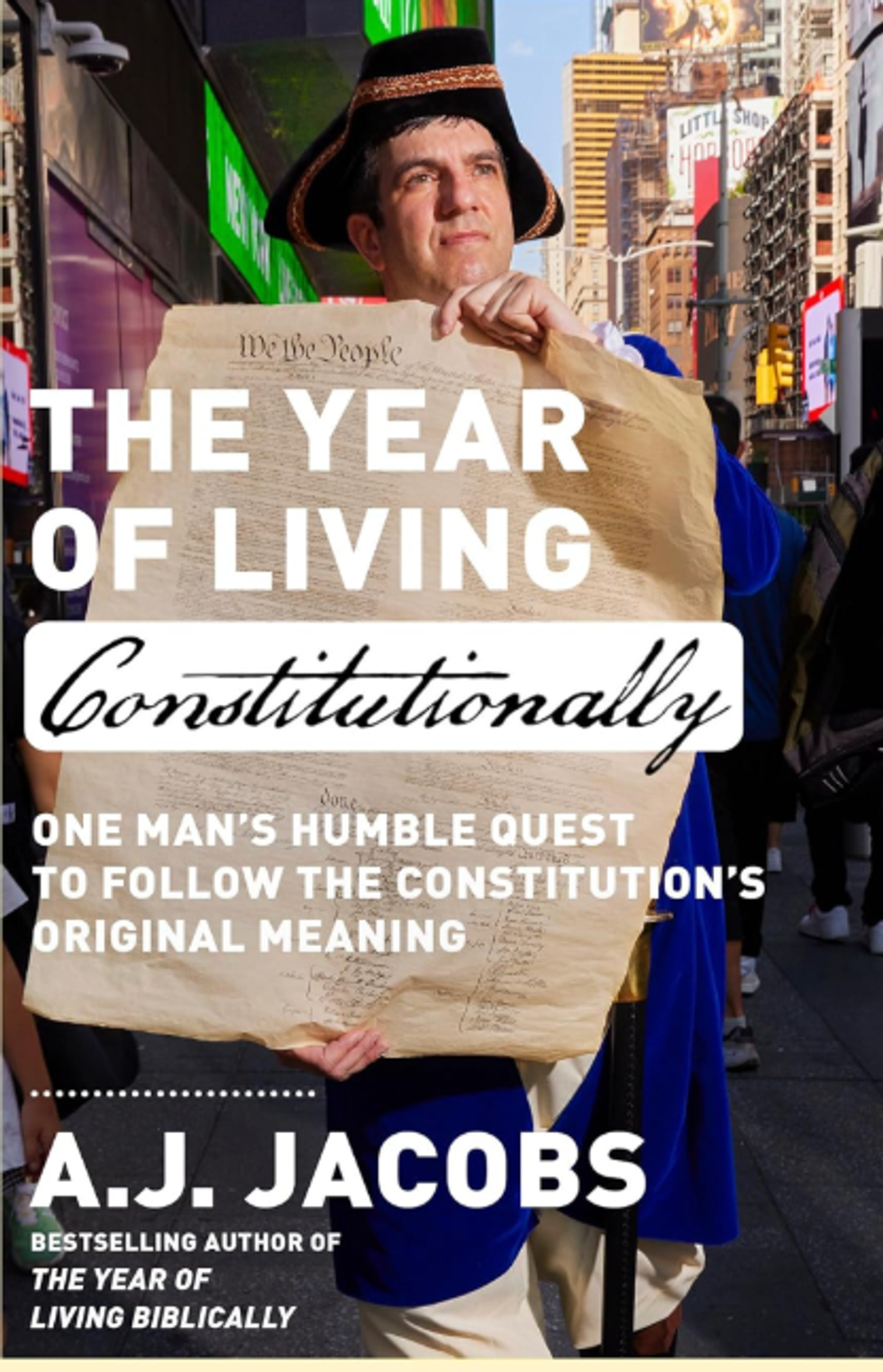

Adapted exclusively from The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man's Humble Quest To Follow The Constitution's Original Meaning, the wise and funny new book by A. J. Jacobs about the pitfalls of "originalism" and the true intentions of the Founders.

Currently, five of the nine justices on the Supreme Court claim to adhere to some version of originalism when deciding their cases.

This raises some questions:

Is originalism the best approach to interpreting the Constitution? Are the justices doing good history and accurately assessing the original public meaning of the text?

I’d answer NAY to both.

But here’s another question that deserves attention:

Is the institution of the Supreme Court as it exists in 2024 what the Founders would have imagined? Is the current Supreme Court an originalist institution?

I would argue NAY freakin’ way. And so would many scholars.

“We’ve created this alternative, strange world in which the judiciary alone has supreme enforcement of the Constitution, which would have shocked most people at the founding,” said Jonathan Gienapp, author of The Second Creation: Fixing the American Constitution in the Founding Era. The Court has gained power at the expense of both Congress and the president.

The idea that nine unelected people have so much say over how we live—over whether we can carry guns, whether we can have access to abortions, or how colleges admit students—seems bonkers on the face of it. And not just bonkers, but as Gienapp says, “deeply unoriginal.”

The Founders would be scratching their bewigged heads at the thought of it.

I came to this conclusion while researching my new book The Year of Living Constitutionally.

The idea of the book was to become the ultimate originalist. I wanted to understand the Constitution’s original meaning by adopting the technology and mindset of the Founding generation — muskets, quill pens, and all. (Fun fact: The book is one of Amazon’s “Best Books of 2024 So Far”).

As part of my research, I visited the Supreme Court itself in the winter of 2023. It did not fill me with confidence in the institution.

My skepticism started with the little things. I didn’t have a press pass to enter, so I visited as a member of the public. This is quite the process. The Court reserves fifty seats for the public. But to be one of those 50, you have to get in line early. Like very early. If it’s a high profile case, you could be in line for days. For low-profile cases, you want to get there in the wee hours the morning of.

I was visiting a low-profile case, so I got up at 3 a.m. and waited in the near-freezing temperatures. I was number 11 in line. The guy in front of me was a bearded man with a Yankees cap. He was lying on the sidewalk, wrapped in a blue tarp, still asleep, a duffel bag of supplies by his side. He knew what he was doing.

He woke up around 6 a.m. and folded his tarp.

“You look like you’re an expert at this,” I said. “Have you seen a lot of cases?”

“I’ve actually never seen one.”

“No?”

“Keep this under your hat, but I’m a professional line waiter.”

You pay him $200 and he’ll wait in line for you.

That annoyed me. It seemed highly undemocratic. SCOTUS is supposed to be the bastion of fairness and equity, and yet you can pay some guy to wait for you and waltz in at 9 a.m. after a restful night's sleep and still get in. It’s un-American. Well, at least it’s contrary to America’s higher ideals, if not its historical reality. (Example: During the Civil War, wealthy Northerners and Southerners would hire people to take their place in the military.)

And then there’s the building itself. It seems to me the very architecture of the Court is contrary to the Founders’ vision.

The Neo-Classical Supreme Court building — with its soaring marble columns, its carved pediment, its famous white steps — looks like it’s from the eighteenth century. It’s not. It was actually built much later, the 1930s.

The SCOTUS building has been nicknamed the Marble Palace. And I think the royal nickname points to the problem. It’s too grandiose. The building was controversial from the start. Construction began in 1932 as a replacement for its humbler digs, a room on the second floor of the Capitol. (Which was several rungs up from the very first location—a converted marketplace in New York City, where the noisy butchers had to be kicked out of the area during Court sessions.)

Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, who was on the Court in the 1930s, called the new building “almost bombastically pretentious . . . wholly inappropriate for a quiet group of old boys such as the Supreme Court,” which I agree with, except for the casual sexism part. Another justice said the building was so pompous it felt as if the justices should enter the courtroom riding on elephants.

But former president and then Chief Justice William Howard Taft pushed it through as his pet project. He thought the Court was underappreciated and wanted the judiciary’s building to rival the Capitol and the White House. He hired architect Cass Gilbert and instructed him to go as regal and Greco-Roman as possible. Only the best materials! The builders got the marble for the columns from Italy with the personal help of Benito Mussolini, himself a fan of pomp.

Pomp and pageantry do have their place. They make people—both citizens and the justices themselves—take the institution seriously. But I say the skeptics have a point: Do we need a faux Roman temple that gives us the feeling we should be sacrificing oxen to Chief Justice John Roberts?

Now let’s move from the building to the justices inside it. How did these nine people become the ultimate arbiters of what is constitutional? How do they have so much power that The Onion can fairly satirize them as saying “we wear gold crowns now.”

The court’s outsize power disturbs critics on both the left and the right. It goes beyond politics. And the tale of how it happened is a strange one.

When the Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution, most of them envisioned the judicial branch as the least powerful branch of government. Third among equals. It’s not a coincidence that the Constitution’s section about the courts appears third, after the sections about the Congress and the president. And it’s by far the shortest of the three—a mere one-sixth the length devoted to Congress.

Here’s just one example of how weak the Supreme Court’s early reputation was: Sometimes one side couldn’t even be bothered to show up. In 1793, a merchant sued the state of Georgia in the Supreme Court. Georgia refused to send a lawyer, deeming the Court unworthy of their valuable time.

According to Professor Gienapp, most Founding Fathers envisioned all three branches—the president, the Congress, and the Supreme Court—weighing in on what is constitutional. It would be a joint decision. SCOTUS was a check on power but not the only voice.

How much of a check? As always, it depended on which Founder you talked to. Alexander Hamilton was a Supreme Court fan, writing in The Federalist Papers that the judiciary must be allowed to declare all acts that were “contrary to . . . the Constitution void.” Thomas Jefferson, however, was a Supreme skeptic. Jefferson wrote to a friend who had endorsed a strong SCOTUS: “You seem to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions; a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.”

Regardless, Gienapp told me that most Founders did not believe the Court should have the final say in constitutional matters. The Court should have modest “judicial review,” meaning it should play a part in deciding what is constitutional. But, Gienapp says, the Founders would be stunned by the situation we have now, which many call “judicial supremacy,” where the nine justices on the Court are the ultimate arbiters.

Professor Gienapp told me to consider the biggest constitutional controversy of the founding era: the establishment of the Bank of the United States. Hamilton loved the idea of a central bank. Jefferson’s camp saw it as a terrifying step toward autocracy and blatantly unconstitutional. Congress debated the bank vigorously, and eventually passed a bill that would establish the bank. President Washington approved it. And SCOTUS? They stayed on the sideline. They had zero input. “Nobody had the slightest sense that there would be this other option that exists after Congress has approved it and the president has signed the bill,” Gienapp said. Unlike now. If this happened today, there would likely be federal lawsuits about the bill’s constitutionality, with SCOTUS having the final say.

So how did the power grab occur?

Often the credit or blame goes to John Marshall, the legendary fourth chief justice. He took over the bench in 1801 and stayed on for 34 years. He was a brilliant and likable character who unified the court. Physically, in fact. He made all the justices live together in a boardinghouse in Washington, D.C., sort of like a highbrow frat house. And like at most frats, there was a lot of drinking.

Marshall established a rule that the justices could only drink if it was raining. But here’s the catch: Even if the sun was shining outside the court’s window, Marshall would say, “Our jurisdiction is so vast that it might be raining somewhere.” And out the bottles of Madeira would come. It was sort of the precursor to the “It’s five o’clock somewhere” argument. And just more proof of Marshall’s genius for finding loopholes.

In 1803, Marshall presided over a case called Marbury v. Madison. The details are a little tricky, so I won’t go into them here, but in the decision, Marshall’s Court invalidated a congressional law.

The traditional narrative says that Marshall’s decision was a stake in the ground. A huge flex. It established SCOTUS as the final word of what is or is not constitutional. But Gienapp and other scholars say this is incorrect. We have misinterpreted the case and given it a modern spin. Marshall was much more modest. He just wanted SCOTUS to be in the mix.

Regardless of whether Marshall believed SCOTUS should have the final say, one thing is certain: Marshall’s Court remained much less powerful than today’s Court. Marshall’s Court never again invalidated a congressional law. Nowadays, SCOTUS routinely invalidates laws.

The Court’s real power grabs occurred much later. One jump took place in the early 1900s, when the conservative court shot down many congressional laws protecting workers during the so-called Lochner Era. Another leap came after World War II with the Warren Court. Earl Warren was chief justice from 1953 to 1969. He was appointed by Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican president. But Warren disappointed Eisenhower by moving to the left and becoming a liberal hero.

During the Warren Court, SCOTUS ruled on dozens of landmark civil rights cases. SCOTUS shot down public school segregation with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. It halted bans on interracial marriages, expanded the right to privacy, and strengthened the rights of criminal suspects. The Court struck down several congressional laws as unconstitutional. Liberals weren’t complaining about SCOTUS’s possible overreach. Why would they? They were getting what they wanted.

But then Warren retired, and a couple of other liberal justices left. Nixon appointed replacements, and suddenly America had a majority-conservative court. The conservatives would retain a majority for decades and wield this expanded SCOTUS power with huge implications—including, most obviously, Bush v. Gore, when the Court decided who would be president of the United States.

Many justices still downplay their power. When John Roberts was nominated in 2005, he said, “It’s my job to call balls and strikes . . . judges are like umpires.”*

But in reality, the justices are more like umpires who call balls and strikes but who also decide with each throw where the strike zone is and claim they have access to Abner Doubleday’s mind and that Abner Doubleday hated knuckleballs, because balls didn’t do that when baseball was invented.

As I write this, the court is at a low ebb of public opinion. According to polls, most Americans view the justices not as objective and impartial arbiters but as men and women who are loyal to their party. The suspicion is that they reason backward. They have a political outcome they want (e.g., looser gun regulations), and they cherry-pick parts of the Constitution to back it up.

And yet, even as the public skepticism grows, the SCOTUS power grabs just continue. Just look at the Loper v Raimondo decision from last week. This decision takes vast power away from regulatory agencies and gives it to the judiciary. We are facing a future where non-scientist judges will be ruling on high-stakes, extremely technical issues that affect our air quality, food safety, AI, and more.

I realize I’ve come out swinging against the court’s current power. But I’m not opposed to moderate judicial review. The court should provide a check on power. An independent judiciary is a good thing. But it should also be held more accountable to the will of the people. One simple step would be to impose 18-year term limits. We also need an ethics code with teeth, as Clarence Thomas’s vacations have made clear. As for other reforms? There are plenty of creative options. Teddy Roosevelt once proposed that the public be allowed to overturn a court decision with a public vote, which would be radical but interesting.

The big point is, we need to rein in the power. In the Constitution, the phrase Supreme Court is not capitalized. It’s the “supreme Court.” Lower case S. Minuscule S, not Majuscule S. Let’s de-majestify the Court.

In my new book, I spent a year trying to be the ultimate originalist. Since the Court’s current power exceeds what is in the Constitution, I figured that maybe I should ignore the Court’s rulings. On the other hand, I don’t want to write a Year of Living Incarceratedly. So I put a pin in that idea.

A.J. Jacobs is a journalist, lecturer and author of several New York Times bestsellers that combine memoir, science, humor, and a dash of self-help. This article is adapted from his latest book, The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man's Humble Quest To Follow The Constitution's Original Meaning (Crown 2024).