It was the start of the 2017 Fall Family Weekend at Liberty University, the school founded by Jerry Falwell Sr. 47 years ago in Lynchburg, Virginia, and the lines were especially long to get into the basketball arena for the mandatory thrice-weekly student convocation. There was a festive feel in the air — as usual, a live band kicked things off with some Christian rock.

Penny Nance, a newly named Liberty trustee who is the head of the socially conservative group Concerned Women for America, took the stage to say that with Donald Trump in the White House, the country was much closer to overturning Roe v. Wade and putting “true limits on the abortionist’s hand.” Tim Lee, a Texas preacher and evangelist who lost his legs in the Vietnam War, gave a sermon bemoaning “homosexuals and pornographers,” declaring that one problem with “pulpits today is that they’ve got a lot of girlie men in them.” A young man in front of me in a Nautica T-shirt clapped and shouted, “That’s right!”

Liberty is spread out on more than 7,000 acres overlooking Lynchburg, a former railroad-and-tobacco town on the James River below the Blue Ridge Mountains. The student body on campus is 15,500 strong, and the university employs more than 7,500 people locally. Throughout the university grounds, there is evidence of a billion-dollar capital expansion: mountains of dirt and clusters of construction equipment marking the site of the new business school; the $40 million football stadium upgrade, to accommodate Liberty’s move into the highest level of N.C.A.A. competition; and the Freedom Tower, which at 275 feet will be the tallest structure in Lynchburg, capped by a replica of the Liberty Bell.

Jerry Falwell Jr., who has led the university since 2007, lacks the charisma and high profile of his father, who helped lead the rise of the religious right within the Republican Party. Yet what the soft-spoken Falwell, 55, lacks in personal aura, he has more than made up for in institutional ambition. As Liberty has expanded over the past two decades, it has become a powerful force in the conservative movement. The Liberty campus is now a requisite stop for Republican candidates for president — with George W. Bush, John McCain and Mitt Romney all making the pilgrimage — and many of Liberty graduates end up working in Republican congressional offices and conservative think tanks.

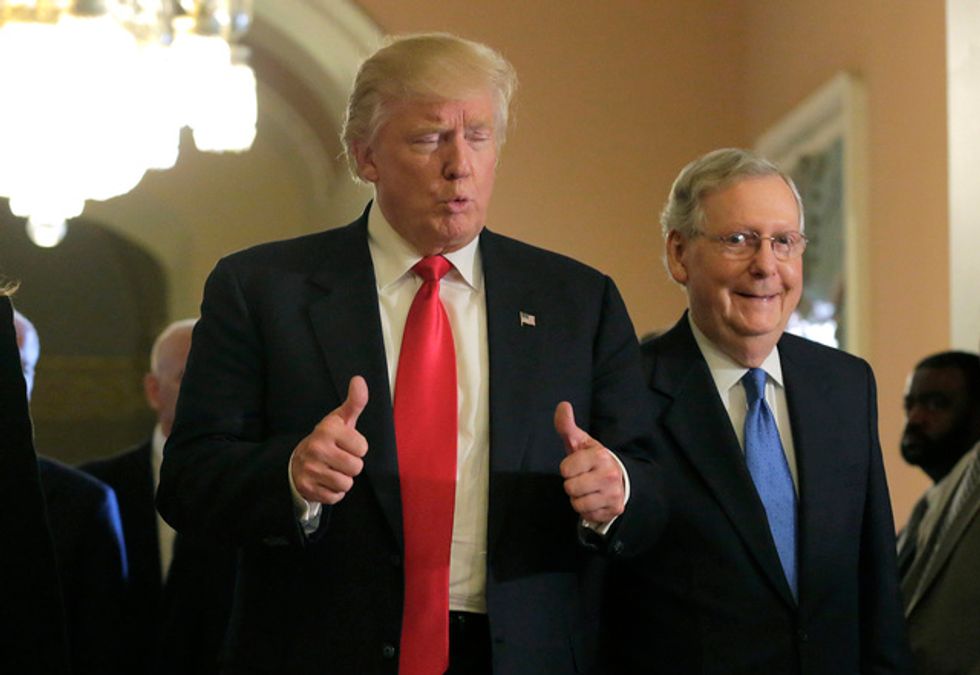

Liberty has also played a significant role in the rise of Donald Trump. Falwell was an early supporter of the reality-TV-star candidate, staying loyal through the release of the “Access Hollywood” tape and giving Trump a crucial imprimatur with white evangelical voters, who widely supported him at the polls. “The evangelicals were so great to me,” Trump said in an interview last year. The first commencement speech he gave as president, last spring, was at Liberty. And in August, Falwell stood by Trump following his much criticized remarks on the violent rally by white supremacists in Charlottesville, declaring on “Fox & Friends” that “President Donald Trump does not have a racist bone in his body.”

Such steadfast allyship has prompted ridicule even from some fellow evangelical Republicans. But it makes more sense in light of an overlooked aspect of Liberty: its extraordinary success as a moneymaking venture. Like Trump, Falwell recognized the money to be made in selling success — in this case, through the booming and lightly regulated realm of online higher education. Falwell’s university has achieved the scale and stature it has because he identified a market opportunity and exploited it.

The real driver of growth at Liberty, it turns out, is not the students who attend classes in Lynchburg but the far greater number of students who are paying for credentials and classes that are delivered remotely, as many as 95,000 in a given year. By 2015, Liberty had quietly become the second-largest provider of online education in the United States, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, its student population surpassed only by that of University of Phoenix, as it tapped into the same hunger for self-advancement that Trump had with his own pricey Trump University seminars. Yet there was a crucial distinction: Trump’s university was a for-profit venture. (This month, a judge finalized a $25 million settlement for fraud claims against the defunct operation.) Liberty, in contrast, is classified as a nonprofit, which means it faces less regulatory scrutiny even as it enjoys greater access to various federal handouts.

By 2017, Liberty students were receiving more than $772 million in total aid from the Department of Education — nearly $100 million of it in the form of Pell grants and the rest in federal student loans. Among universities nationwide, it ranked sixth in federal aid. Liberty students also received Department of Veterans Affairs benefits, some $42 million in 2016, the most recent year for which figures are available. Although some of that money went to textbooks and nontuition expenses, a vast majority of Liberty’s total revenue that year, which was just above $1 billion, came from taxpayer-funded sources.

And it was no secret which part of the university was generating most of that revenue, said Chris Gaumer, a Liberty graduate and former professor of English there. “When I was there, at faculty meetings the commentary was that online was funding the school, while they were trying to just break even on the residential side,” he said. “It was understood that on the online side, they were making a killing.”

Jerry Falwell Sr. was raised in Lynchburg by a Christian mother and a nonbelieving father, whose knack for business gained him a small empire of restaurants, bus lines, nightclubs and gas stations and eventually carried him into bootlegging. Falwell cast this dual inheritance in the terms of a clash between God and the Enemy, but it was hard not to see his career as a successful fusing of his parents’ influences, salesmanship wrapped in Christian cloth.

He founded Thomas Road Baptist Church in the former offices of a bottling company in 1956 and soon began broadcasting recordings of his sermons on regional radio and television. In 1971, the same year his “Old Time Gospel Hour” went national, he founded Lynchburg Baptist College, subsidizing it with revenues from the show. “I believe there are thousands of young students who will catch the vision and who will carry what God is doing in Lynchburg to cities all over the continent and around the world,” he declared at the time, according to his 1996 autobiography. At first the college was scattered in rented spaces around town — a vacant high school, a Ramada Inn — but by 1977 it had been renamed Liberty Baptist College and moved up to an initial 2,000-acre swath of land on the mountain.

By 1984, nearly 400 local broadcasters around the nation were carrying “The Old Time Gospel Hour.” The toll-free number flashing on the screen reportedly helped bring in more than $72 million per year in donations. Some $10 million of those funds flowed to the college, which at that point numbered about 4,500 students. Another of Falwell’s enterprises pulled in about $12 million a year — the Moral Majority, an attempt to build a cross-denominational political coalition against the common foes of abortion rights and, as he later put it, “moral permissiveness, family breakdown and general capitulation to evil and to foreign policies such as Marxism-Leninism.”

Liberty University, as it has been named since 1985, grew steadily, drawing families attracted by the “Liberty Way,” which forbade premarital sex, drinking, smoking and cussing. In 1987, it secured tax-exempt status, which Falwell described in his autobiography as an existential necessity: “If a tax exemption could not be granted us,” he wrote, “it would have been impossible to carry out the dream of a 50,000-student Christian university in Lynchburg.”

But another element of the business model — evangelical broadcasting’s aura of rectitude — was about to take a hit. That March, Jim Bakker resigned as head of the televangelist PTL ministry amid revelations of a sexual encounter with a former church secretary, Jessica Hahn, who received a payoff to keep quiet about it; Bakker later served just under five years in prison on a federal fraud conviction related to PTL’s fund-raising. In 1988, the televangelist Jimmy Swaggart declared, “I have sinned,” following reports of his consorting with a prostitute in New Orleans; three years later, the police pulled him over with another prostitute in Southern California.

No such scandals attached to Falwell, who succeeded Bakker as host of “The PTL Club.” But the bubble had burst. Amid what Falwell later referred to as the “credibility crunch” caused by the televangelist scandals, the college’s finances deteriorated. Within a few years, annual contributions dropped by $25 million; the college’s debt swelled to more than $100 million.

In 1996, the accrediting body overseeing Liberty presented a list of more than 100 “recommendations” for staying accredited, including a demand that it reduce its debt. Falwell went on a 40-day liquids-only fast, praying for deliverance. “I am certain that we will become a world-class university training champions for Christ in every important field of study,” Falwell vowed in his autobiography. “And I am asking God to give me more time to guide and fund that dream.”

One educational novelty that Falwell dabbled in, starting in the mid-70s, was an early form of distance learning. Liberty would mail lecture videotapes and course packets to paying customers around the country — at first just certificate courses in Bible studies, and by the mid-80s, accredited courses in other subjects as well. By the time of Liberty’s financial embattlement, other education innovators had taken the idea much further — none more so than a man named John Sperling.

Sperling was an unlikely capitalist entrepreneur. The son of a failed farmer in the Missouri Ozarks, he joined the Merchant Marine, embraced socialism and ended up receiving a Ph.D. in history from the University of Cambridge. He got a job teaching at San Jose State University, where he took over the faculty union and led a big strike in 1968. His humble origins and early socialist leanings had given him a jaundiced view of elite schools, and his experience teaching a course to police officers and teachers as part of a federally funded effort to reduce juvenile delinquency furthered his belief that traditional colleges were leaving out a whole swath of Americans eager for higher education. He decided to start a university of his own — not a nonprofit but a for-profit, and not in California, where he had clashed with skeptical accreditors, but in the laxer regulatory climate of Arizona.

In 1976, Sperling rented space in a boilermakers’ union hall in Phoenix and started offering weekly classes there to eight students — all adults who’d had some college education and were looking to complete their degrees. A decade later, University of Phoenix had 6,000 students. But things really took off three years later, in 1989, when Sperling started offering MBAs online through Prodigy, the early electronic communications service. Sperling took the university’s parent company public in 1994; by 2000, enrollment had reached 100,000.

By the early 2000s, for-profit colleges were booming: Access to the internet was spreading, and the Bush administration was employing a notably light regulatory touch, even as the programs were devouring an ever-greater share of federal student aid. Among the adopters of Sperling’s model was Falwell, who in 2004 began expanding the family’s primitive distance-learning programs into what would become known as Liberty University Online.

In his autobiography, Falwell praised Jerry Jr.’s business instincts, crediting him with saving Liberty from ruin through his management of its debt. “God sent him to me just in time,” he wrote. “He is more responsible, humanly speaking, for the miraculous financial survival of this ministry than any other single person.” When Falwell died in 2007 at age 73, his younger son, Jonathan, took over the pulpit at Thomas Road Baptist, and Jerry Jr. took over the university — an indication of where the heart of the ministry now was.

As the Great Recession hit, laid-off Americans turned to online education to seek a new economic foothold. After years of trying to save Liberty by cutting costs, Falwell Jr. said, he adopted his father’s vision of saving it through increasing revenues. In a recent telephone interview, Falwell described the surge in online enrollment as a kind of revelation. “It took us about 20 years to perfect” the distance-learning model, he said, “but when we did, that was about when everyone started getting high-speed internet in their homes, and we were the only nonprofit poised to serve that huge adult market of people who had not finished college or needed a master’s degree to get a promotion.”

Liberty had another advantage over online competitors, he said: its status as a religious-based institution, “that long history of Liberty being a leader among Christian universities,” the “faith-based mission” that “makes us so unique and puts us in a class by ourselves.”

The River Ridge Mall spreads out on the flat ground below Liberty’s campus, among motels and fast-food restaurants. Like much commercial real estate in Lynchburg, it is majority-owned by Liberty University. In 2013, the mall lost one of its anchor tenants, Sears, which occupied a 112,000-square-foot space behind gray, nearly windowless walls. The retailer was replaced by Liberty University Online. When it first arrived inside the mall, the L.U.O. operation numbered 675 employees; it grew so large that in 2015 L.U.O. began moving its operation into a former Nationwide Insurance building several miles away.

At the front lines are the “admissions representatives,” some 300 phone recruiters working two shifts from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., deploying call lists that Liberty gets from websites where people register and search for information about online higher education, like BestCollegesOnline.com. There is such a race to get to customers before University of Phoenix and other rivals that the prospective students sometimes marvel at how little time has elapsed — just a handful of minutes — between their providing their information on a website and the call coming from Liberty. Liberty’s tax filings show that in 2016, the university paid Google $16.8 million for “admissions leads generation.” In other words, advertising Liberty to those searching online for degree options.

The recruiters work under intense pressure, according to several former L.U.O. employees I spoke with. They get no more than 45 seconds between calls, and sometimes managers override even that short break. There are no formal quotas — a federal regulation that went into effect in 2011 forbids them. But as one former employee put it, the “highly motivated goal” is for each recruiter to sign up eight new students a day. Multiplied across 300 cubicles, that is 2,400 per day. Of those, only a small fraction end up paying and starting courses, but that is still an extraordinary haul for any kind of education business.

Every day, according to the former employee, managers send out a report showing the previous day’s tallies. Recruiters who signed up four or fewer new students get their names in red, visible for all to see, and are sometimes subject to a disciplinary conversation. Monthly tallies are also scored as green, yellow or red. Top performers are in the running for a small raise from the base salary, which is about $30,000. “It was that carrot and stick,” the former employee told me.

A separate division of about 60 people focuses on courting members of the military, who have access to even greater federal tuition assistance, and then advising them on campus. A former employee in that division said that given the smaller crew, the work there was if anything even more intense than in the main branch: More than 30,000 L.U.O. students are from the military or military families.

Two recruiters told me they were instructed to quote L.U.O.’s cost on a per-credit basis, rather than per-course, which makes it sound more affordable. Undergraduate courses for part-time students are $455 per credit, or $1,365 for a typical course; master’s courses are typically about $600 per credit. They are instructed not to press prospective applicants too hard on their academic qualifications. Applicants have to submit past transcripts, but any grade point average above 0.5 — equivalent to a D-minus — would suffice, said the former employee in the nonmilitary division. Recruiters, he told me, “would say, ‘Congratulations, you’ve been accepted.’ They’d make it seem competitive.”

The two recruiters also said they were told not to mention Liberty’s Christian orientation until people agree to apply, when this fact is made clear in the user agreement they sign online. It also becomes clear at the moment that the recruiters sign up students for their first classes, typically an orientation class and three required Bible studies classes. Students often can’t transfer credits for these courses to other colleges, which deters many from dropping out: Leaving L.U.O. without signing up for more courses would mean wasting the money spent on the first four.

Falwell and other top Liberty officials pushed back on some of these points in my interview with them, insisting, for instance, that the minimum G.P.A. for applicants is 2.0 and that recruiters are assessed according to “the same H.R. evaluation form that’s standard across the university.” But Ron Kennedy, the executive vice president for online enrollment management, acknowledged that the recruiters working under pressure to meet their targets might say otherwise. “It’s a call center,” he said.

In 2010, undercover investigators from the Government Accountability Office scrutinized 15 for-profit colleges, finding that every one of them had misled applicants and that four had encouraged them to lie on their federal student-aid forms. The Obama administration seized on the findings as it began a yearslong clampdown on for-profit education, which by 2013 was gobbling up a fifth of all federal student aid, more than $25 billion, despite enrolling only 10 percent of students — and also producing about a third of all federal student loan defaults.

Liberty, too, was hugely reliant on federal money, in the form of Pell grants, Department of Veterans Affairs benefits and federally subsidized loans. By 2010, it had more than 50,000 students enrolled and was pulling in more than $420 million annually. But because Liberty was technically not for-profit, it was spared many of the administration’s new regulations, including its requirement that a certain threshold of graduates be able to attain “gainful employment,” which was designed to hit for-profit colleges much harder. It was also spared from the pre-existing rule that for-profit colleges could get no more than 90 percent of their revenue from federal sources.

If anything, Liberty benefited from the crackdown. The Obama administration’s actions helped put out of business large for-profit chains like Corinthian and ITT Technical Institute, clearing formidable competition from the field. Though there were other nonprofit institutions with online offerings — Arizona State, Southern New Hampshire and Western Governors, as well as premium players like Stanford and Duke — none were operating at Liberty’s scale. The university now touts itself on its website as “the largest private nonprofit university in the nation.” In a sense, said Ben Miller, who served as a senior policy adviser in Obama’s Department of Education, the crackdown on for-profits offered Liberty a “marketing advantage.”

Falwell was candid about the benefits of the nonprofit status. “It insulated us from the attack on the for-profits,” he told me. And it put him on the same footing with other, more established universities. “There’s no way that an Obama federal government that probably doesn’t care much for schools like Liberty can treat us different than Harvard or Yale or Indiana Wesleyan or the University of Maryland.”

Liberty’s ability to distance itself from for-profit colleges was especially notable given that, by several key metrics, it resembled them more closely than the private nonprofits it was grouped with. The rate of Liberty graduates who default on their loans within three years of graduating is 9.9 percent, several points higher than the average for nonprofit colleges, though still below that for for-profit colleges. Most striking, though, is how little the university spends on actual instruction. It does not report separate figures for spending on the online school and the traditional college. But according to its most recent figures, from 2016, the university reports spending only $2,609 on instruction per full-time equivalent student across both categories. That is a fraction of what traditional private universities spend (Notre Dame’s equivalent figure is $27,391) but also well behind even University of Phoenix, which spends more than $4,000 per student in many states. It is also behind other hybrid online-traditional nonprofit religious colleges like Ohio Christian University, which spends about $4,500. In 2013, according to an audited financial statement I obtained, Liberty received $749 million in tuition and fees but spent only $260 million on instruction, academic support and student services.

By 2016, Liberty’s net assets had crossed the $1.6 billion mark, up more than tenfold from a decade earlier. Thanks to its low spending on instruction, its net income was an astonishing $215 million on nearly $1 billion in revenue, according to its tax filing — making it one of the most lucrative nonprofits in the country, based simply on the difference between its operating revenue and expenses, in a league with some of the largest nonprofit hospital systems.

Falwell, whose Liberty salary is nearly $1 million, does not apologize for those margins. Liberty, he said, is simply being shrewd about keeping costs down, while plowing revenue back into the university. He noted proudly that Liberty’s net assets are now $2.5 billion, up from just $150 million in 2007, when he took over. He said he was surprised more universities weren’t following Liberty’s example of increasing online enrollment by keeping instructional spending and tuition low. And he freely acknowledged that the online revenues were going to buttress the residential campus. From Falwell’s perspective, there was nothing wrong with the university’s benefiting so much from the online program. “As long as we’re keeping the quality up, we don’t think it’s a disservice to anyone,” he said. “All that is, is ensuring the future of the university.”

Students at Liberty often quote a favorite line of Falwell Sr.’s: “If it’s Christian, it ought to be better.” Even those who have misgivings about the university’s conservative culture are quick to defend the education they’ve received on campus. Yet despite its ambitions to become the “evangelical Notre Dame” that Falwell envisioned, Liberty is still ranked well behind that university and other religious-based institutions like Brigham Young and Pepperdine; U.S. News and World Report clumps Liberty in the lowest quartile of institutions in its “national universities” category. Some of its programs have strong reputations, among them nursing, engineering and flight school. But the college is limited in its ability to compete for premier faculty, not only because its politics are out of step with the greater academic community, but also because none of its programs, with the exception of its law school, offer tenure.

In his autobiography, Falwell made virtually no distinction between these students on the Lynchburg campus and those receiving their instruction remotely. All of them, in his telling, were being prepared for the same goal, to be “Champions for Christ,” as the Liberty motto had it. But many students on campus, at least, are openly dismissive of the online experience. They take some classes online, for the convenience of not having to drag themselves to class — and, they readily admit, for the ease of not having to study much. “People know it’s kind of a joke and don’t learn that much from it,” Dustin Wahl, a senior from South Dakota, told me. “You use Google when you take your quiz and don’t have to work as hard. It’s pretty obvious.” (Liberty says using Google during quizzes or exams is cheating.)

Campus students are especially scornful of the online discussion boards that are in theory meant to replicate the back and forth of a classroom, but that in reality tend to be a rote exercise, with students making only their requisite one post and two comments per week, generating no substantive discussion. “It’s very minimal engagement,” said Alexander Forbes, a senior from California. Recently, a satirical campus newspaper, The Flaming Bugle, ran an Onion-style article with the headline “Cat Playing on Keyboard Inadvertently Earns ‘A’ for Discussion Board Post.”

Chris Gaumer taught English courses both on campus and online at Liberty after getting his bachelor’s degree on campus in 2006. The difference between the two forms of teaching was startling, he told me. As an online instructor, he said, he was not expected to engage in the delivery of any actual educational content. That was all prepared separately by L.U.O.’s team of course designers and editors, who assemble curriculums and videotaped lectures by other Liberty professors. This leaves little for the instructor to do in the courses, which typically run eight weeks. “As professor, you show up and your job is to handle emails and grade,” Gaumer said. This helps explain why the instructors — the roughly 2,400 adjuncts scattered around the country, plus the Liberty professors who agree to teach online courses on the side — are willing to take on the task for what’s long been the going rate for the job: $2,100 per course. (Falwell Jr. said it will soon go up to $2,700.)

Until recently, the course designers and editors, a team of about 30 people, worked out of the old Thomas Road Baptist Church — the congregation moved out of the former bottling plant years earlier — in a concrete room that got so cold in winter that they sometimes kept scarves and hats on. For editors, starting pay is now around $11 per hour. As L.U.O. boomed in size, they became so overwhelmed by the challenge of shaping hundreds of courses that L.U.O. decided in 2015 to focus designers and editors on the hundred or so highest-enrollment courses per term, leaving the maintenance of the remaining hundreds of courses up to the instructors themselves. One former editor recalled having a professor send a syllabus along with, essentially, an apology for throwing something together at the last minute.

Gaumer, who now works at Randolph College in Lynchburg, said the steep drop-off in quality from the traditional college to the online courses was both openly acknowledged among Liberty faculty and not fully reckoned with. The reason was plain, he said: Everyone knew that L.U.O. was subsidizing the physical university. “The motivation behind the growth seems to be almost entirely economic, because it’s not as if the education is getting any better,” he said.

Falwell acknowledged that Liberty’s faculty initially resisted the rise of the online program, fearing the degradation of academic standards. “The big victory was finding a way to tame the faculty,” he said. But he disputed that there was any great difference in quality. For one thing, he said, the university made sure that all of its online instructors “adhere to the fundamentals of the Christian faith, our doctrinal statement.” Physical distance was a challenge, he said, but online instructors overcame it by making an extra effort to reach out. “They spend a lot more time taking a personal interest in the students,” he said.

One of the 65,000 students who enrolled with L.U.O. in 2013 was Megan Hart, a woman from New Jersey with unflaggingly high spirits. Hart, who is in her 40s, started her working life at the glass company where her father worked, too, until he was laid off. From there, Hart made her way into education, teaching communications at the local community college and the local prison. Adjunct courses at the college paid just $525 per credit, netting her only about $5,000 per semester, so she got a low-level administrative job there, too.

Her first marriage, to the father of her daughter, ended in divorce. In January 2012, her second husband suddenly vanished. Hart and her daughter, then 9 years old, lost their home shortly afterward, and she filed for bankruptcy. She and her daughter moved into her parents’ basement and got by with donations from her local Assemblies of God church, where she was active. In 2013, she signed up to take three courses at L.U.O. that would provide her with a certificate in communications, allowing her to become a full-time instructor at the community college, which would reimburse her L.U.O. tuition.

Hart, who had a master’s in communications and leadership through Pat Robertson’s Regent University, chose L.U.O. because of its affordability and Christian cachet. But in her years of teaching and taking courses, she said, she had never seen anything as flimsy as what L.U.O. passed off in its supposedly graduate-level courses. She had little interaction with the instructor, and the questions for the midterm and final exams were so arbitrary that it seemed to Hart as if they had been randomly generated by a computer program. She spent the open-book exams wildly flipping back and forth through the textbook and course materials trying to find the relevant passages. It was, she wrote to L.U.O. officials later, like “looking for Waldo.”

When she wrote the instructor for the second class to ask about the test, he responded: “As to exam question, I have no clue how the final is run.” He said he’d get back to her. He ended his note, “Do remember that God is in control and he works all things for our good.”

When Hart emailed the instructor for her third course, which had a closed-book exam, she confirmed Hart’s suspicions: “The exam questions are random.” Hart got good grades in the first two courses but was increasingly convinced she was paying for a meaningless experience. She sent an email outlining her concerns to the instructor and an L.U.O. academic mentor, adding that she might quit the third course. “We will certainly take your input very seriously,” the mentor responded. “May the Lord bless you richly in your studies and future endeavors.”

Finally, Hart told the officials that she was withdrawing from the third course, even though she had been informed that she would still have to pay 25 percent of the cost. “My spirit has been so sick over what I have experienced,” she wrote. In late 2013, she filed a complaint with a little-known government agency called the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, which oversees the state’s colleges.

Between 2009 and summer 2017, L.U.O. students filed 49 complaints with the council, more than for any other institution in the state. For some, the problem was administrative bungling — L.U.O. registered them for the wrong class, or required a class it turned out they didn’t need, and so on. For some, it was endless technical or logistical troubles that kept them from being able to submit their assignments or get textbooks. For others, it was disputes about tuition and financial aid that left them feeling as if L.U.O. was demanding more money than was fair, and withholding their transcripts until they paid up.

Several complainants said they were particularly taken aback by their L.U.O. experiences because of Liberty’s religious underpinnings. “I just expected that Liberty University being a Christian university,” they’d be more helpful, wrote a complainant who went to prison and then become homeless after a stint enrolled in L.U.O. He had been seeking to have his transcript released despite his still having a balance at L.U.O., so that he could resume his education elsewhere; Liberty responded by recommending homeless shelters. “Liberty’s motto is they are a Christian school that is training champions for Christ and they are the light of the world,” another student wrote six years ago. “That motto needs to be revised.”

The anodyne responses the students received from L.U.O. were frequently glossed with Christian bromides. To a student whose financial aid was suspended in 2015 after the student failed a course because the textbook didn’t arrive in time, an instructor sent “quiz tips that may help” that included “Eat a healthy meal before taking your quiz” and “Pray before beginning each quiz!” Other L.U.O. responses included language errors so extreme that they bordered on confusing: One administrator wrote in 2014 about a complainant’s having submitted work that “appeared to have been copied from an unsighted source,” while a professor responded to a student in 2012 that “no other acceptions will be made.”

Other students were left simply to flounder, contrary to Falwell’s claims of close attention from distant instructors. Lydia Terry-Dominelli, who lives in a suburb of Albany, New York, signed up with Liberty in 2013, when it looked as if she and her husband were headed for divorce and she was worrying about how she could support herself and her 9-year-old daughter. She decided to get her teacher’s certification and chose Liberty partly because she was an observant Anglican. “I was ready for something that had some kind of value system,” she told me.

In 2015, Terry-Dominelli failed a graduate-level education course when, she said, one of the assignments she submitted vanished from Blackboard, the online system used by Liberty. After twice failing a writing course and puzzling over what she was doing wrong, she asked the course instructor for an explanation. He wrote back to suggest that she might do better if she found a “new work space” like the local library. After she assured him that her apartment sufficed and the conversation continued, he wrote: “I wonder if you can’t find a great prayer group through L.U.O.?”

Terry-Dominelli struggled further with confusing assignments in another graduate-level education course. She was starting to feel helpless over the lack of guidance. “I have prayed very hard, and what I keep being told is I am in the wrong place,” she wrote to the education instructor in late October of 2015.

“Bless your heart. I am so sorry,” the instructor responded. “I will join you in prayer for you to have wisdom and discernment.”

In early 2016, Terry-Dominelli was unable to access online the spring semester courses she had registered for. She took it as a final sign and left Liberty, just a few courses short of the master’s degree she had borrowed more than $20,000 to pay for. In August 2016, having failed to establish a decent income, she moved back in with her husband. Lacking certification, she took a part-time job as an aide at a local elementary school. Unable to afford the loans she’d taken out, she filed for help under the Department of Education’s Borrower Defense program, which is intended for students who have incurred student debt after being misled by higher education programs. (Her application is still pending.)

She also filed a complaint with the Virginia agency: “I feel that I was being pushed out of the program and I need to know why,” she had written to one of her professors. The agency declined to take action, finding no clear violations by Liberty. “What’s killing me is that I went into this program to try to change my situation,” she told me, “and I’m worse off than I was at the beginning.”

The Trump-Falwell bond has if anything grown even stronger in recent months. In October, Falwell Jr. told Breitbart News that Trump could “be the greatest president since Abraham Lincoln” and urged an evangelical army to rise up against the “fake Republicans” standing in his way. In December, he joined Trump in promoting Roy Moore’s Senate candidacy, quoting the song “Sweet Home Alabama” in a tweet on the eve of Election Day: “AL voters are too smart to let the media & Estab Repubs & Dems tell them how to vote. I hope the spirit of Lynyrd Skynyrd is alive/well in AL. ‘A southern man don’t need them around anyhow & Watergate does not bother me, does your conscience bother you, tell me true?’” In late February, he joined in on Trump’s mau-mauing of Jeff Sessions, calling the attorney general a “coward” in a tweet for his handling of the Russia investigation.

But on campus, Falwell has proved a more divisive leader than his father. In May 2016, conflict over his pro-Trump stance prompted the resignation of the chairman of the university board of trustees’ executive committee, Mark DeMoss, whose father was a major donor to the university. DeMoss previously told The Washington Post that “the bullying tactics of personal insult have no defense — and certainly not for anyone who claims to be a follower of Christ.” It also prompted students on campus, including Wahl and Forbes, to gather hundreds of signatures in opposition to Trump following the release of the “Access Hollywood” tape. After Falwell’s support for Trump following Charlottesville, several Liberty graduates mailed back their degrees in protest. One protester was Laura Honnol, a banking officer in Lubbock, Texas, who attended from 2003 to 2007. “There’s been a huge climate shift from Falwell Senior to Falwell Junior,” she told me. “You felt like you disagreed with Senior, but he had good intentions and just didn’t do it right sometimes. But Junior came along, and it’s become more of a profit machine and a numbers machine.”

The Trump connection is not without risk for Falwell. Some people who worked for L.U.O. in late 2016 and early 2017 blamed it for a dip in applications at the time and said the decline led to an April 2017 leadership overhaul and the departure of many employees. Falwell told me that Liberty has deliberately brought online enrollment down to around 85,000, explaining that “we wanted to make sure we kept the student quality at a certain standard.” And he said that his alliance with Trump has only helped the university: “For every student we lost because of political concerns, we picked up two or three inquiries who support us because of that political stand.”

A relationship with Trump could benefit Falwell Jr. and Liberty in other ways too. One of the top orders of business for Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, has been to roll back Obama-era regulations on online-degree providers. She named a former official from for-profit DeVry University to lead the D.O.E. unit that polices fraud in higher education. Claims for student debt relief under the Borrower Defense program are being considered at a far slower rate under DeVos, who is delaying by two years an Obama rule that would make it easier to file debt relief claims. And DeVos is expected shortly to roll back several key regulations geared toward online providers: ones giving states regulatory powers over distance-learning programs, establishing clear standards for a credit hour and requiring “regular and substantive” interactions between online instructors and students. Falwell told me that Liberty officials have had a major hand in some of DeVos’s actions: “A lot of what we sent them is actually what got implemented,” he said.

After the convocation on the first weekend in November, I met with Dustin Wahl in Liberty’s student center, overlooking the campus quad. He said that the unbridled success of the online program couldn’t help putting him in mind of the profit-seeking tradition within American Christianity, which is closely aligned with evangelical Christianity’s prosperity gospel — the notion that financial success, far from distracting us from the higher values, is an affirmation of godliness. Wahl told me he’d frequently heard people justify the school’s new wealth in these terms. “A lot of people just talk about it generally, how God has blessed us,” he said.

Falwell rejects such prosperity-gospel talk. “I’m not going to tell you that we’ve done better because we’re better people,” he told me. “What I will say is that we’ve always operated from a business perspective. We’ve treated it like a business.” And that’s what first drew him to Trump, he said: the kinship of one businessman to another. “I thought to myself, if there’s one thing this country needs, it’s exactly the methods we employed at Liberty to save the school and make it prosper, and that’s just basic business principles.”

As I sat with Wahl, the spoils of that prosperity were visible all around us: not just gleaming new buildings like the $50 million library with its robotic book-retrieval system, but also, up the mountain, a $7 million “Snowflex Centre,” with a polymer surface for year-round skiing — the only one of its kind at any university in the country. Elsewhere, the university is completing a $3 million shooting range. But, Wahl said, once you knew about the thousands of people far from Lynchburg who funded this splendor, it was hard to take your mind off them, and off the faith with which they signed up for L.U.O. “You get a phone call,” he said, “and it’s God telling you, ‘I’ll give you an education.’ “

When we spoke before my visit, Wahl raved about the campus: “It’s beautiful,” he said. Then he added: “And it’s funded by the online program that’s sold to people who can’t really afford college.”