Rethinking The ‘Infrastructure’ Discussion Amid A Blitz Of Hurricanes

Reprinted with permission from ProPublica.

The wonky words infrastructure and resilience have circulated widely of late, particularly since Hurricanes Harvey and Irma struck paralyzing, costly blows in two of America’s fastest-growing states.

Resilience is a property traditionally defined as the ability to bounce back. A host of engineers and urban planners have long warned this trait is sorely lacking in America’s brittle infrastructure.

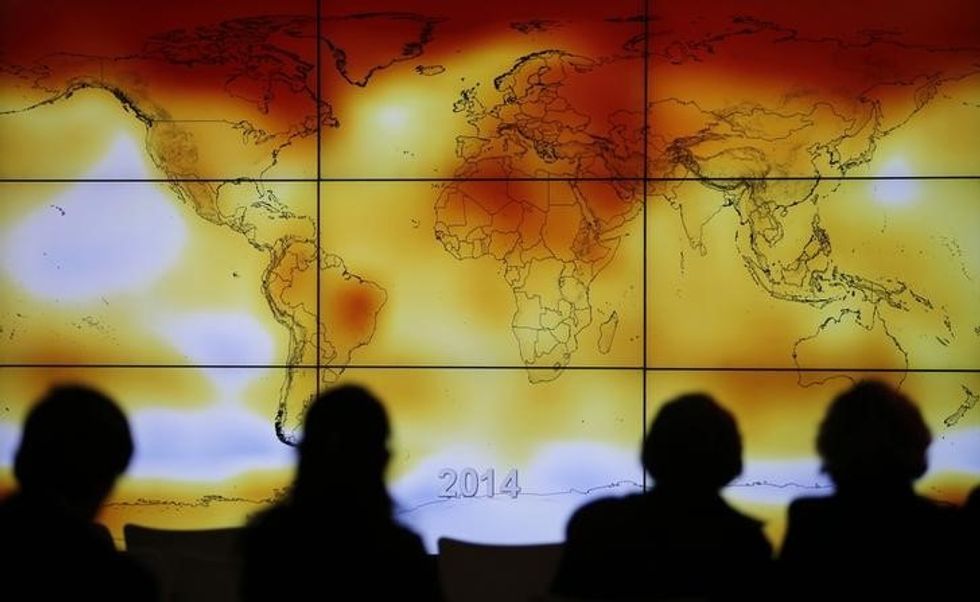

Many such experts say the disasters in the sprawling suburban and petro-industrial landscape around Houston and along the crowded coasts of Florida reinforce the urgent idea that resilient infrastructure is needed more than ever, particularly as human-driven climate change helps drive extreme weather.

The challenge in prompting change — broadening the classic definition of “infrastructure,” and investing in initiatives aimed at adapting to a turbulent planet — is heightened by partisan divisions over climate policy and development.

Of course, there’s also the question of money. The country’s infrastructure is ailing already. A national civil engineering group has surveyed the nation’s bridges, roads, dams, transit systems and more and awarded a string of D or D+ grades since 1998. The same group has estimated that the country will be several trillion dollars short of what’s needed to harden and rebuild and modernize our infrastructure over the next decade.

For fresh or underappreciated ideas, ProPublica reached out to a handful of engineers, economists and policy analysts focused on reducing risk on a fast-changing planet.

Alice Hill, who directed resilience policy for the National Security Council in the Obama administration, said the wider debate over cutting climate-warming emissions may have distracted people from promptly pursuing ways to reduce risks and economic and societal costs from natural disasters.

She and several other experts said a first step is getting past the old definition of resilience as bouncing back from a hit, which presumes a community needs simply to recover.

“I don’t think of resilience in the traditional sense, in cutting how long it takes to turn the lights back on,” said Brian Bledsoe, the director of the Institute for Resilient Infrastructure Systems at the University of Georgia. “Resilience is seizing an opportunity to move into a state of greater adaptability and preparedness — not just going back to the status quo.”

In thinking about improving the country’s infrastructure, and provoking real action, Bledsoe and others say, language matters.

Bledsoe, for instance, is exploring new ways to communicate flood risk in words and maps. His institute is testing replacements for the tired language of 1-in-100 or 1-in-500-year floods. A 100-year flood has a 1 in 4 chance of occurring in the 30-year span of a typical home mortgage, he said, adding that’s the kind of time scale that gets people’s attention.

Visual cues matter, too, he said. On conventional maps, simple lines marking a floodplain boundary often are interpreted as separating safe zones and those at risk, Bledsoe said. But existing models of water flows don’t provide the full range of possible outcomes: “A 50-year rain can produce a 100-year flood if it falls on a watershed that’s already soaked or on snowpack or if it coincides with a storm surge.”

“The bright line on a map is an illusion,” he said, particularly in flat places like Houston, where a slight change in flood waters can result in far more widespread inundation. Risk maps should reflect that uncertainty, and wider threat.

Nicholas Pinter, a University of California, Davis, geoscientist who studies flood risk and water management, said that Florida is well-situated to build more wisely after this disaster because it already has a statewide post-disaster redevelopment plan and requires coastal communities to have their own.

It’s more typical to have short-term recovery plans — for digging out and getting the lights back on, as 20,000 utility workers are scurrying to do right now.

The advantage of having an established protocol for redevelopment, he said, is it trims delays.

“Draw up plans when the skies are blue and pull them off the shelf,” he said of how having rebuilding protocols in place can limit repeating mistakes. “That fast response cuts down on the horrible lag time in which people typically rebuild in place.”

In a warming climate, scientists see increasing potential for epic deluges like the one that swamped Houston and last year’s devastating rains around Baton Rouge, Louisiana. How can the federal government more responsibly manage such environmental threats?

Many people point to the National Flood Insurance Program, which was created to boost financial resilience in flood zones, but has been criticized from just about every political and technical vantage point as too often working to subsidize, instead of mitigate, vulnerability.

As has happened periodically before, pressure is building on Congress to get serious about fixing the program (a reauthorization deadline was just pushed from this month toward the end of the year).

How this debate plays out will have an important impact on infrastructure resilience, said Pinter of the University of California, Davis. If incentives remain skewed in favor of dangerous and sprawling development, he said, that just expands where roads, wires, pipelines and other connecting systems have to be built. “Public infrastructure is there in service of populations,” he said.

He also said the lack of federal guidance has led to deeply uneven enforcement of floodplain building at the state level, with enormous disparities around the country resulting in more resilient states, in essence, subsidizing disaster-prone development in others.

“Why should California, Wyoming or Utah be paying the price for Houston, Mississippi or Alabama failing to enforce the National Flood Insurance Program? ” he said.

Bledsoe, at the University of Georgia, said there’s no need to wait for big changes in the program to start making progress. He said the National Flood Insurance Program has a longstanding division, the Community Rating System, that could swiftly be expanded, cutting both flood risk and budget-breaking payouts. It’s a voluntary program that reduces flood insurance rates for communities that take additional efforts beyond minimum standards to reduce flood damage to insurable property.

Despite the clear benefits, he said, only one municipality, Roseville, California, has achieved the top level of nine rankings and gotten the biggest insurance savings — 45 percent. Tulsa, Oklahoma, Fort Collins, Colorado, King County, Washington, and Pierce County, Washington, are at the second ranking and get a 40 percent rate cut. Hundreds of other municipalities are at much lower levels of preparedness.

“Boosting participation is low-hanging fruit,” Bledsoe said.

Some see signs that the recent blitz of hurricanes is reshaping strategies in the Trump White House. President Donald Trump’s infrastructure agenda, unveiled on August 15, centered on rescinding Obama-era plans to require consideration of flood risk and climate change in any federal spending for infrastructure or housing and the like. The argument was built around limiting perceived red tape.

After the flooding of Houston less than two weeks later, Trump appointees, including Tom Bossert, the president’s homeland security adviser, said a new plan was being developed to insure federal money would not increase flood risks.

On Monday, as Irma weakened over Georgia, Bossert used a White House briefingto offer more hints of an emerging climate resilience policy, while notably avoiding accepting climate change science: “What President Trump is committed to is making sure that federal dollars aren’t used to rebuild things that will be in harm’s way later or that won’t be hardened against the future predictable floods that we see. And that has to do with engineering analysis and changing conditions along eroding shorelines but also in inland water and flood-control projects.”

Robert R.M. Verchick, a Loyola University law professor who worked on climate change adaptation policy at the Environmental Protection Agency under Obama, said federal leadership is essential.

If Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps incorporated future climate conditions, that move would send a ripple effect into real estate and insurance markets, forcing people to pay attention, he said. If the federal government required projected climate conditions to be considered when spending on infrastructure in flood-prone areas, construction practices would change, he added, noting the same pressures would drive chemical plants or other industries to have a wider margin of safety.

“None of these things will change without some form of government intervention. That’s because those who make decisions on the front end (buying property, building bridges) do not bear all the costs when things go wrong on the back end,” he wrote in an email. “And on top of that, human beings tend to discount small but important risks when it seems advantageous in the short-run.”

After a terrible storm, he said, most Americans are willing to cheer a government that helps communities recuperate. But people should also embrace the side of government that establishes rules to avoid risk and make us safer. That’s harder, he said, because such edicts can be perceived by some as impinging on personal freedom.

“But viewed correctly, sensible safeguards are part of freedom, not a retreat from it,” he said. “Freedom is having a home you can return to after the storm. Freedom is having a bridge high enough to get you to the hospital across the river. Freedom is not having your house surrounded by contaminated mud because the berm at the neighboring chemical plant failed overnight.”

“Fundamentally, we must abandon the idea that there is a specific standard to which we can control nature and instead understand that we are creating complex and increasingly difficult-to-control systems that are part social, part ecological and part technological. These mean not just redesigning the infrastructure, but redesigning institutions and their knowledge systems.”

After the destruction and disruption from Hurricane Sandy, New York City didn’t just upgrade its power substations and subway entrances, Miller said in a subsequent phone call. The city also rebooted its agencies’ protocols and even job descriptions. “Every time a maintenance crew opens a sewer cover, fixes or installs a pipe, whether new or retrofitting, you’re thinking how to enhance its resilience,” Miller said.

Miller said another key to progress, particularly when federal action is limited or stalled, is cooperation between cities or regions. Heat was not an issue in Oregon historically, Miller said, but it’s becoming one. The light rail system around Portland was designed to work with a few 90-degree days a year, he said. “The last couple of summers have seen 20-plus 90-degree days,” he said, causing copper wires carrying power for the trains to sag and steel rails to expand in ways that have disrupted train schedules. Similar rail systems in the Southwest deal with such heat routinely, said Miller, who has worked in both regions. The more crosstalk, the better the outcome, he said.

“At the broadest level, we need to think about risks and how infrastructure is built to withstand them at a landscape level,” Miller added. “We can longer commit to evaluating the impacts and risks of a single project in isolation against a retrospective, stationary understanding of risk (e.g., the 100-year flood we’ve been hearing so much about.)”

He said that an emerging alternative, “safe-to-fail” design, is more suited to situations where factors contributing to extreme floods or other storm impacts can’t be fully anticipated. “Safe-to-fail infrastructure might allow flooding, but in ways that are designed for,” he said.

(With an Arizona State colleague, Mikhail Chester, Miller offered more details in a commentary published last week by The Conversation website, laying out “six rules for rebuilding infrastructure in an era of ‘unprecedented’ weather events.”)

Deborah Brosnan, an environmental and disaster risk consultant, said the challenge in making a shift to integrating changing risks into planning and investments is enormous, even when a community has a devastating shock such as a hurricane or flood or both:

“It requires a radical shift in how we incorporate variability in our planning and regulations,” she said. “This can and will be politically difficult. New regulations like California fire and earthquake codes and Florida’s building codes are typically enacted after an event, and from a reactive ‘make sure this doesn’t happen again’ perspective. The past event creates a ‘standard’ against which to regulate. Regulations and codes require a standard that can be upheld, otherwise decisions can be arbitrary and capricious. For climate change, non-stationarity would involve creating regulations that take account of many different factors and where variability has to be included. Variability (uncertainy) is the big challenge for these kinds of approaches.”

Stephane Hallegatte, the lead economist at the Word Bank’s Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, has written or co-written a host of reports on strategies for limiting impacts of climate change and disasters, particularly on the poor. When asked in an email exchange what success would look like, he said the World Bank, in various recent reports, has stressed the importance of managing disaster risks along two tracks: both designing and investing to limit the most frequent hard knocks and then making sure the tools and services are available to help communities recover when a worst-case disaster strikes.

He added: “Facing a problem, people tend to do one thing to manage it, and then forget about it. (‘I face floods; I build a dike; I’m safe.’) We are trying to work against this, by having risk prevention and contingent planning done together.”

Andrew Revkin is a senior reporter at ProPublica covering climate and related issues.