6 Of First 20 ‘Worst Of The Worst’ Still At Guantanamo

By Carol Rosenberg, Miami Herald (TNS)

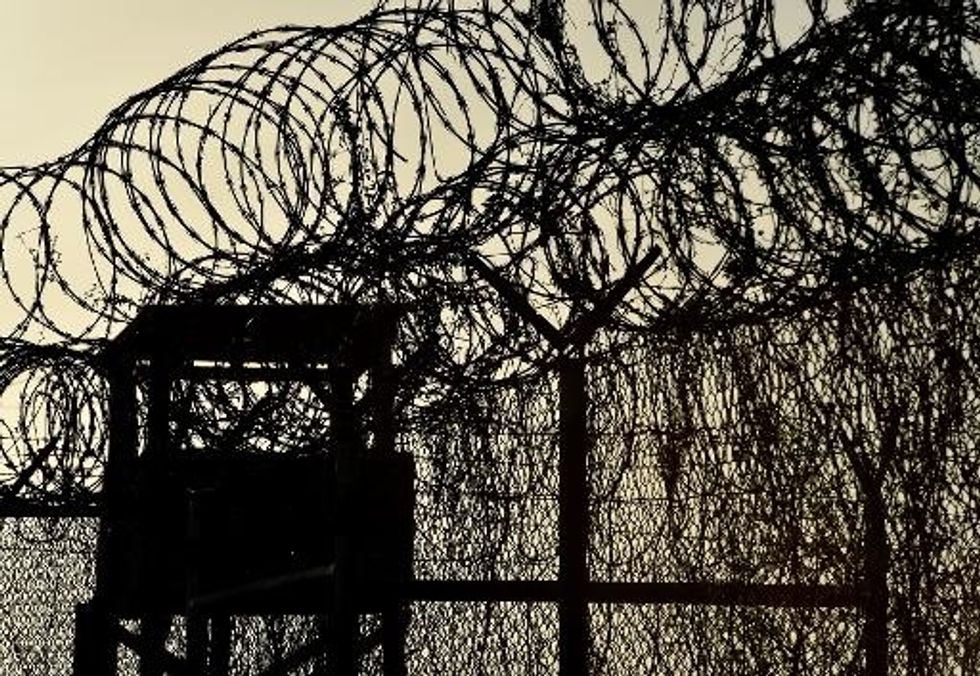

MIAMI — Fourteen years ago, a Navy photographer hoisted a camera over razor wire and made an iconic image of America’s experiment in law-of-war detention: 20 men in orange jumpsuits in shackles on their knees in their first hours at Guantanamo.

Today, just six of those first 20 captives who opened the U.S. prison camps in Cuba are still there. And in a sense they symbolize President Barack Obama’s challenge in downsizing if not closing the offshore prison.

Four of them are Arab men who, on paper, are cleared to go but not to their home countries. Another has never gotten a hearing at the parole board Obama created in 2011 that bogged down in bureaucracy.

And the sixth is Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, 46, Guantanamo’s lone convicted war criminal. A 2008 military tribunal sentenced him to life in prison for serving as Osama bin Laden’s media secretary and creating a crude al-Qaida recruiting video.

Little is known about how al-Bahlul, a 46-year-old Yemeni, has spent his years alone on Guantanamo’s cellblock for convicts. But his case is emerging as a crucial test of the on-again, off-again military commissions. A federal appeals court is deciding whether to uphold his conspiracy conviction as a violation of the law of war, a decision expected this year that could shape up as the next U.S. Supreme Court challenge over Guantanamo.

The prison entered its 15th year on Jan. 11 amid a period of downsizing that should reduce the number of detainees to 90 by February. More than a third of those remaining are approved for transfer — like Day One detainees Mahmud Mujahid, 35; Abdel Malik Wahab al-Rahabi, 36; Samir al Hassan Moqbel, 38; and Ridah Bin Saleh al-Yazidi, 50. The first three are from Yemen; the last is Tunisian.

But as long as al-Bahlul’s life sentence stands and Congress continues to insist that no Guantanamo captive set foot on U.S. soil, Guantanamo is the Pentagon’s version of Spandau Prison. Spandau didn’t close in West Berlin until four decades after World War II ended when its last Nazi prisoner died.

Meantime, Marine Gen. John F. Kelly, who has run the prison from Miami’s Southern Command for three years, says the 2,000 soldiers and civilians who staff the prison shoulder the responsibility “superbly.” Thousands of troops have come and gone across the years since the first flight set down at the remote U.S. Navy base with these last six men aboard it.

Al-Yazidi, the Tunisian, may be the most mysterious to this day. His leaked 2007 Guantanamo profile cast him as a veteran of the battle for Tora Bora in Afghanistan who twice fled his native Tunisia for Italy, first in the ’80s to work in a Sicilian vineyard. Later, according to U.S. military intelligence, he migrated to Afghanistan where he reportedly forged “numerous connections to senior al-Qaida officials, including Osama bin Laden.”

But by late 2009, a federal task force approved his release “to a country that will implement appropriate security measures.” So, in theory, al-Yazidi could go home — unless he or the State Department fears sending him there.

“I just don’t know,” said his attorney of record, Brent Rushforth, who met al-Yazidi only once in 2008. Since then, the Tunisian has refused calls and invitations to other meetings. “He’s certainly mysterious as far as I’m concerned; I just haven’t been able to communicate with him.”

Also curious is how another captive who got there on Day One — Yemeni Mohammed Abu Ghanim, 40, never charged with a crime — has also never been before the parole board. Like other detainees who have been released, Ghanim was brought to Guantanamo as a suspected bin Laden bodyguard. Under Obama’s March 2011 executive order, all captives were supposed to have their cases reviewed within a year and have twice yearly file reviews thereafter. But only 16 of the captives currently at Guantanamo have gotten hearings.

Getting an appointment at the parole board, said Navy Cmdr. Gary Ross by email, is “a function of many variables.” He said that includes “the quantity and type of information available about a detainee,” in this case a man who got there the day the detention center opened, as well as how much time a U.S. military officer tasked with helping the captive needs to prepare.

Two men on that first flight, Mujahid and al-Rahabi, were cleared to go in 2014 by the Obama parole board. But they’re Yemenis who can’t go home under a longstanding White House policy that considers Yemen too violent, too influenced by al-Qaida offshoots for Guantanamo repatriations.

“They’re conscious of the irony that they were the first in,” says their attorney, David Remes. In December, Rahabi lamented that although he was the first “forever prisoner” cleared by the parole board, no foreign country has interviewed him as a candidate for resettlement.

Al-Rahabi, like most of Remes’ Guantanamo clients, “is willing to go anywhere” to be reunited with his wife and daughter Ayesha, whom he last saw in person as a 3-month-old. He aspires, however, “to be transferred to an Arabic-speaking country because that’s where the family would have the easiest time integrating,” Remes said.

Also still there is Moqbel, who briefly captured attention with his April 2013 New York Times op-ed column about his hunger strike and forced feedings. He’s been cleared for release since late 2009 and wrote his lawyers in July that he aspires to own a business, maybe run a restaurant.

Meantime, the sailor who took the photo has moved on. Former Petty Officer Shane McCoy has left the Navy, where he worked with a Combat Camera Unit, for a civilian job with the U.S. Marshals Service. He’s the first and only photographer at the federal agency that moves federal prisoners around and into the United States.

Fourteen years ago, at Guantanamo, McCoy was uniquely situated to capture the arrival of the first 20 captives. Now, he said, if President Obama is ever able to move the last Guantanamo detainees to the United States, he wants to photograph them that day, too.

©2016 Miami Herald. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: In this photo released Jan. 18, 2002 by the Department of Deense, U.S. Army military police secort a detainee to his scell in Camp X-Ray during in-processing on Jan. 11, 2002, the day the dentention center opened. (Shane T. McCoy – U.S. Navy Petty Officer)