How A Private Security Outfit Helped Cyber-Criminals

Reprinted with permission from ProPublica

This story was co-published with MIT Technology Review.

On Jan. 11, antivirus company Bitdefender said it was "happy to announce" a startling breakthrough. It had found a flaw in the ransomware that a gang known as DarkSide was using to freeze computer networks of dozens of businesses in the U.S. and Europe. Companies facing demands from DarkSide could download a free tool from Bitdefender and avoid paying millions of dollars in ransom to the hackers.

But Bitdefender wasn't the first to identify this flaw. Two other researchers, Fabian Wosar and Michael Gillespie, had noticed it the month before and had begun discreetly looking for victims to help. By publicizing its tool, Bitdefender alerted DarkSide to the lapse, which involved reusing the same digital keys to lock and unlock multiple victims. The next day, DarkSide declared that it had repaired the problem, and that "new companies have nothing to hope for."

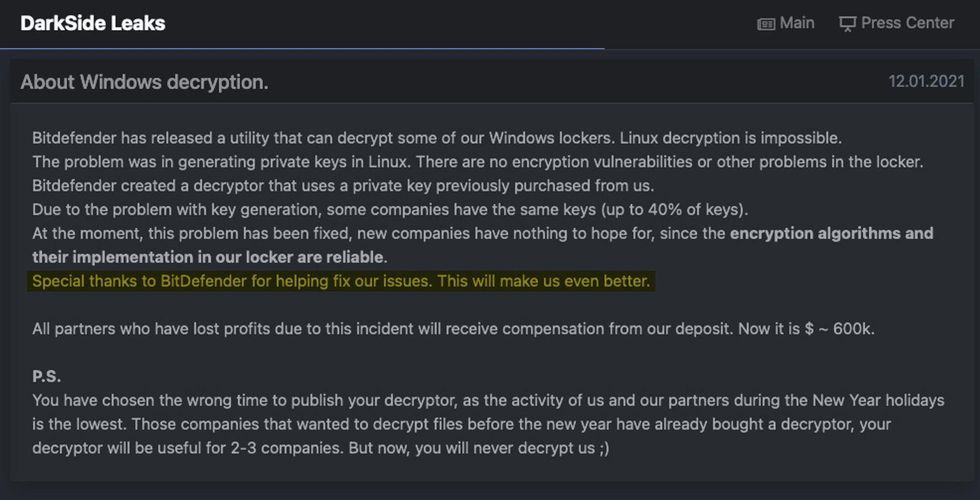

"Special thanks to BitDefender for helping fix our issues," DarkSide said. "This will make us even better."

DarkSide soon proved it wasn't bluffing, unleashing a string of attacks. This month, it paralyzed the Colonial Pipeline Co., prompting a shutdown of the 5,500 mile pipeline that carries 45 percent of the fuel used on the East Coast, quickly followed by a rise in gasoline prices, panic buying of gas across the Southeast and closures of thousands of gas stations. Absent Bitdefender's announcement, it's possible that the crisis might have been contained, and that Colonial might have quietly restored its system with Wosar and Gillespie's decryption tool.

Instead, Colonial paid DarkSide $4.4 million in Bitcoin for a key to unlock its files. "I will admit that I wasn't comfortable seeing money go out the door to people like this," CEO Joseph Blount told The Wall Street Journal.

The missed opportunity was part of a broader pattern of botched or half-hearted responses to the growing menace of ransomware, which during the pandemic has disabled businesses, schools, hospitals and government agencies across the country. The incident also shows how antivirus companies eager to make a name for themselves sometimes violate one of the cardinal rules of the cat-and-mouse game of cyber-warfare: Don't let your opponents know what you've figured out.

During World War II, when the British secret service learned from decrypted communications that the Gestapo was planning to abduct and murder a valuable double agent, Johnny Jebsen, his handler wasn't allowed to warn him for fear of cluing in the enemy that its cipher had been cracked. Today, ransomware hunters like Wosar and Gillespie try to prolong the attackers' ignorance, even at the cost of contacting fewer victims. Sooner or later, as payments drop off, the cybercriminals realize that something has gone wrong.

Whether to tout a decryption tool is a "calculated decision," said Rob McLeod, senior director of the threat response unit for cybersecurity firm eSentire. From the marketing perspective, "You are singing that song from the rooftops about how you have come up with a security solution that will decrypt a victim's data. And then the security researcher angle says, 'Don't disclose any information here. Keep the ransomware bugs that we've found that allow us to decode the data secret, so as not to notify the threat actors.'"

In a post on the dark web, DarkSide thanked Bitdefender for identifying a flaw in the gang's ransomware. (Highlight added by ProPublica.)

Wosar said that publicly releasing tools, as Bitdefender did, has become riskier as ransoms have soared and the gangs have grown wealthier and more technically adept. In the early days of ransomware, when hackers froze home computers for a few hundred dollars, they often couldn't determine how their code was broken unless the flaw was specifically pointed out to them.

Today, the creators of ransomware "have access to reverse engineers and penetration testers who are very very capable," he said. "That's how they gain entrance to these oftentimes highly secured networks in the first place. They download the decryptor, they disassemble it, they reverse engineer it and they figure out exactly why we were able to decrypt their files. And 24 hours later, the whole thing is fixed. Bitdefender should have known better."

It wasn't the first time that Bitdefender trumpeted a solution that Wosar or Gillespie had beaten it to. Gillespie had broken the code of a ransomware strain called GoGoogle and was helping victims without any fanfare, when Bitdefender released a decryption toolin May 2020. Other companies have also announced breakthroughs publicly, Wosar and Gillespie said.

"People are desperate for a news mention, and big security companies don't care about victims," Wosar said.

Bogdan Botezatu, director of threat research at Bucharest, Romania-based Bitdefender, said the company wasn't aware of the earlier success in unlocking files infected by DarkSide. Regardless, he said, Bitdefender decided to publish its tool "because most victims who fall for ransomware do not have the right connection with ransomware support groups and won't know where to ask for help unless they can learn about the existence of tools from media reports or with a simple search."

Bitdefender has provided free technical support to more than a dozen DarkSide victims, and "we believe many others have successfully used the tool without our intervention," Botezatu said. Over the years, Bitdefender has helped individuals and businesses avoid paying more than $100 million in ransom, he said.

Bitdefender recognized that DarkSide might correct the flaw, Botezatu said. "We are well aware that attackers are agile and adapt to our decryptors." But DarkSide might have "spotted the issue" anyway. "We don't believe in ransomware decryptors made silently available. Attackers will learn about their existence by impersonating home users or companies in need, while the vast majority of victims will have no idea that they can get their data back for free."

The attack on Colonial Pipeline, and the ensuing chaos at the gas pumps throughout the Southeast, appears to have spurred the federal government to be more vigilant. President Joe Biden issued an executive order to improve cybersecurity and create a blueprint for a federal response to cyberattacks. DarkSide said it was shutting down under U.S. pressure, although ransomware crews have often disbanded to avoid scrutiny and then re-formed under new names, or their members have launched or joined other groups.

"As sophisticated as they are, these guys will pop up again, and they'll be that much smarter," said Aaron Tantleff, a Chicago cybersecurity attorney who has consulted with 10 companies attacked by DarkSide. "They'll come back with a vengeance."

At least until now, private researchers and companies have often been more effective than the government in fighting ransomware. Last October, Microsoft disrupted the infrastructure of Trickbot, a network of more than 1 million infected computers that disseminated the notorious Ryuk strain of ransomware, by disabling its servers and communications. That month, ProtonMail, the Swiss-based email service, shut down 20,000 Ryuk-related accounts.

Wosar and Gillespie, who belong to a worldwide volunteer group called the Ransomware Hunting Team, have cracked more than 300 major ransomware strains and variants, saving an estimated 4 million victims from paying billions of dollars.

By contrast, the FBI rarely decrypts ransomware or arrests the attackers, who are typically based in countries like Russia or Iran that lack extradition agreements with the U.S. DarkSide, for instance, is believed to operate out of Russia. Far more victims seek help from the Hunting Team, through websites maintained by its members, than from the FBI.

The U.S. Secret Service also investigates ransomware, which falls under its purview of combating financial crimes. But, especially in election years, it sometimes rotates agents off cyber assignments to carry out its better-known mission of protecting presidents, vice presidents, major party candidates and their families. European law enforcement, especially the Dutch National Police, has been more successful than the U.S. in arresting attackers and seizing servers.

Similarly, the U.S. government has made only modest headway in pushing private industry, including pipeline companies, to strengthen cybersecurity defenses. Cybersecurity oversight is divided among an alphabet soup of agencies, hampering coordination. The Department of Homeland Security conducts "vulnerability assessments" for critical infrastructure, which includes pipelines.

It reviewed Colonial Pipeline in around 2013 as part of a study of places where a cyberattack might cause a catastrophe. The pipeline was deemed resilient, meaning that it could recover quickly, according to a former DHS official. The department did not respond to questions about any subsequent reviews.

Five years later, DHS created a pipeline cybersecurity initiative to identify weaknesses in pipeline computer systems and recommend strategies to address them. Participation is voluntary, and a person familiar with the initiative said that it is more useful for smaller companies with limited in-house IT expertise than for big ones like Colonial. The National Risk Management Center, which oversees the initiative, also grapples with other thorny issues such as election security.

Ransomware has skyrocketed since 2012, when the advent of Bitcoin made it hard to track or block payments. The criminals' tactics have evolved from indiscriminate "spray and pray" campaigns seeking a few hundred dollars apiece to targeting specific businesses, government agencies and nonprofit groups with multimillion-dollar demands.

Attacks on energy businesses in particular have increased during the pandemic — not just in the U.S. but in Canada, Latin America and Europe. As the companies allowed employees to work from home, they relaxed some security controls, McLeod said.

Since 2019, numerous gangs have ratcheted up pressure with a technique known as "double extortion." Upon entering a system, they steal sensitive data before launching ransomware that encodes the files and makes it impossible for hospitals, universities and cities to do their daily work. If the loss of computer access is not sufficiently intimidating, they threaten to reveal confidential information, often posting samples as leverage. For instance, when the Washington, D.C., police department didn't pay the $4 million ransom demanded by a gang called Babuk last month, Babuk published intelligence briefings, names of criminal suspects and witnesses, and personnel files, from medical information to polygraph test results, of officers and job candidates.

DarkSide, which emerged last August, epitomized this new breed. It chose targets based on a careful financial analysis or information gleaned from corporate emails. For instance, it attacked one of Tantleff's clients during a week when the hackers knew the company would be vulnerable because it was transitioning its files to the cloud and didn't have clean backups.

To infiltrate target networks, the gang used advanced methods such as "zero-day exploits" that immediately take advantage of software vulnerabilities before they can be patched. Once inside, it moved swiftly, looking not only for sensitive data but also for the victim's cyber insurance policy, so it could peg its demands to the amount of coverage. After two to three days of poking around, DarkSide encrypted the files.

"They have a faster attack window," said Christopher Ballod, associate managing director for cyber risk at Kroll, the business investigations firm, who has advised half a dozen DarkSide victims. "The longer you dwell in the system, the more likely you are to be caught."

Typically, DarkSide's demands were "on the high end of the scale," $5 million and up, Ballod said. One scary tactic: If publicly traded companies didn't pay the ransom, DarkSide threatened to share information stolen from them with short-sellers who would profit if the share price dropped upon publication.

DarkSide's site on the dark web identified dozens of victims and described the confidential data it claimed to have filched from them. One was New Orleans law firm Stone Pigman Walther Wittmann. "A big annoyance is what it was," attorney Phil Wittmann said, referring to the DarkSide attack in February. "We paid them nothing," said Michael Walshe Jr., chair of the firm's management committee, declining to comment further.

Last November, DarkSide adopted what is known as a "ransomware-as-a-service" model. Under this model, it partnered with affiliates who launched the attacks. The affiliates received 75 to 90 percent of the ransom, with DarkSide keeping the remainder. As this partnership suggests, the ransomware ecosystem is a distorted mirror of corporate culture, with everything from job interviews to procedures for handling disputes. After DarkSide shut down, several people who identified themselves as its affiliates complained on a dispute resolution forum that it had stiffed them. "The target paid, but I did not receive my share," one wrote.

Together, DarkSide and its affiliates reportedly grossed at least $90 million. Seven of Tantleff's clients, including two companies in the energy industry, paid ransoms ranging from $1.25 million to $6 million, reflecting negotiated discounts from initial demands of $7.5 million to $30 million. His other three clients hit by DarkSide did not pay. In one of those cases, the hackers demanded $50 million. Negotiations grew acrimonious, and the two sides couldn't agree on a price.

DarkSide's representatives were shrewd bargainers, Tantleff said. If a victim said it couldn't afford the ransom because of the pandemic, DarkSide was ready with data showing that the company's revenue was up, or that COVID-19's impact was factored into the price.

DarkSide's grasp of geopolitics was less advanced than its approach to ransomware. Around the same time that it adopted the affiliate model, it posted that it was planning to safeguard information stolen from victims by storing it in servers in Iran. DarkSide apparently didn't realize that an Iranian connection would complicate its collection of ransoms from victims in the U.S., which has economic sanctions restricting financial transactions with Iran. Although DarkSide later walked back this statement, saying that it had only considered Iran as a possible location, numerous cyber insurers had concerns about covering payments to the group. Coveware, a Connecticut firm that negotiates with attackers on behalf of victims, stopped dealing with DarkSide.

Ballod said that, with their insurers unwilling to reimburse the ransom, none of his clients paid DarkSide, despite concerns about exposure of their data. Even if they had caved in to DarkSide, and received assurances from the hackers in return that the data would be shredded, the information might still leak, he said.

During DarkSide's changeover to the affiliate model, a flaw was introduced into its ransomware. The vulnerability caught the attention of members of the Ransomware Hunting Team. Established in 2016, the invitation-only team consists of about a dozen volunteers in the U.S., Spain, Italy, Germany, Hungary and the U.K. They work in cybersecurity or related fields. In their spare time, they collaborate in finding and decrypting new ransomware strains.

Several members, including Wosar, have little formal education but an aptitude for coding. A high school dropout, Wosar grew up in a working-class family near the German port city of Rostock. In 1992, at the age of 8, he saw a computer for the first time and was entranced. By 16, he was developing his own antivirus software and making money from it. Now 37, he has worked for antivirus firm Emsisoft since its inception almost two decades ago and is its chief technology officer. He moved to the U.K. from Germany in 2018 and lives near London.

He has been battling ransomware hackers since 2012, when he cracked a strain called ACCDFISA, which stood for "Anti Cyber Crime Department of Federal Internet Security Agency." This fictional agency was notifying people that child pornography had infected their computers, and so it was blocking access to their files unless they paid $100 to remove the virus.

The ACCDFISA hacker eventually noticed that the strain had been decrypted and released a revised version. Many of Wosar's subsequent triumphs were also fleeting. He and his teammates tried to keep criminals blissfully unaware for as long as possible that their strain was vulnerable. They left cryptic messages on forums inviting victims to contact them for assistance or sent direct messages to people who posted that they had been attacked.

In the course of protecting against computer intrusions, analysts at antivirus firms sometimes detected ransomware flaws and built decryption tools, though it wasn't their main focus. Sometimes they collided with Wosar.

In 2014, Wosar discovered that a ransomware strain called CryptoDefense copied and pasted from Microsoft Windows some of the code it used to lock and unlock files, not realizing that the same code was preserved in a folder on the victim's own computer. It was missing the signal, or "flag," in their program, usually included by ransomware creators to instruct Windows not to save a copy of the key.

Wosar quickly developed a decryption tool to retrieve the key. "We faced an interesting conundrum," Sarah White, another Hunting Team member, wrote on Emsisoft's blog. "How to get our tool out to the most victims possible without alerting the malware developer of his mistake?"

Wosar discreetly sought out CryptoDefense victims through support forums, volunteer networks and announcements of where to contact for help. He avoided describing how the tool worked or the blunder it exploited. When victims came forward, he supplied the fix, scrubbing the ransomware from at least 350 computers. CryptoDefense eventually "caught on to us ... but he still did not have access to the decrypter we used and had no idea how we were unlocking his victims' files," White wrote.

But then an antivirus company, Symantec, uncovered the same problem and bragged about the discovery on a blog post that "contained enough information to help the CryptoDefense developer find and correct the flaw," White wrote. Within 24 hours the attackers began spreading a revised version. They changed its name to CryptoWall and made $325 million.

Symantec "chose quick publicity over helping CryptoDefense victims recover their files," White wrote. "Sometimes there are things that are better left unsaid."

A spokeswoman for Broadcom, which acquired Symantec's enterprise security business in 2019, declined to comment, saying that "the team members who worked on the tool are no longer with the company."

Like Wosar, the 29-year-old Gillespie comes from poverty and never went to college. When he was growing up in central Illinois, his family struggled so much financially that they sometimes had to move in with friends or relatives. After high school, he worked full time for 10 years at a computer repair chain called Nerds on Call. Last year, he became a malware and cybersecurity researcher at Coveware.

Last December, he messaged Wosar for help. Gillespie had been working with a DarkSide victim who had paid a ransom and received a tool to recover the data. But DarkSide's decryptor had a reputation for being slow, and the victim hoped that Gillespie could speed up the process.

Gillespie analyzed the software, which contained a key to release the files. He wanted to extract the key, but because it was stored in an unusually complex way, he couldn't. He turned to Wosar, who was able to isolate it.

The teammates then began testing the key on other files infected by DarkSide. Gillespie checked files uploaded by victims to the website he operates, ID Ransomware, while Wosar used VirusTotal, an online database of suspected malware.

That night, they shared a discovery.

"I have confirmation DarkSide is re-using their RSA keys," Gillespie wrote to the Hunting Team on its Slack channel. A type of cryptography, RSA generates two keys: a public key to encode data and a private key to decipher it. RSA is used legitimately to safeguard many aspects of e-commerce, such as protecting credit numbers. But it's also been co-opted by ransomware hackers.

"I noticed the same as I was able to decrypt newly encrypted files using their decrypter," Wosar replied less than an hour later, at 2:45 a.m. London time.

Their analysis showed that, before adopting the affiliate model, DarkSide had used a different public and private key for each victim. Wosar suspected that, during this transition, DarkSide introduced a mistake into its affiliate portal used to generate the ransomware for each target. Wosar and Gillespie could now use the key that Wosar had extracted to retrieve files from Windows machines seized by DarkSide. The cryptographic blunder didn't affect Linux operating systems.

"We were scratching our heads," Wosar said. "Could they really have fucked up this badly? DarkSide was one of the more professional ransomware-as-a-service schemes out there. For them to make such a huge mistake is very, very rare."

The Hunting Team celebrated quietly, without seeking publicity. White, who is a computer science student at Royal Holloway, part of the University of London, began looking for DarkSide victims. She contacted firms that handle digital forensics and incident response.

"We told them, 'Hey listen, if you have any DarkSide victims, tell them to reach out to us, we can help them. We can recover their files and they don't have to pay a huge ransom,'" Wosar said.

The DarkSide hackers mostly took the Christmas season off. Gillespie and Wosar expected that, when the attacks resumed in the new year, their discovery would help dozens of victims. But then Bitdefender published its post, under the headline "Darkside Ransomware Decryption Tool."

In a messaging channel with the ransomware response community, someone asked why Bitdefender would tip off the hackers. "Publicity," White responded. "Looks good. I can guarantee they'll fix it much faster now though."

She was right. The next day, DarkSide acknowledged the error that Wosar and Gillespie had found before Bitdefender. "Due to the problem with key generation, some companies have the same keys," the hackers wrote, adding that up to 40% of keys were affected.

DarkSide mocked Bitdefender for releasing the decryptor at "the wrong time…., as the activity of us and our partners during the New Year holidays is the lowest."

Adding to the team's frustrations, Wosar discovered that the Bitdefender tool had its own drawbacks. Using the company's decryptor, he tried to unlock samples infected by DarkSide and found that they were damaged in the process. "They actually implemented the decryption wrong," Wosar said. "That means if victims did use the Bitdefender tool, there's a good chance that they damaged the data."

Asked about Wosar's criticism, Botezatu said that data recovery is difficult, and that Bitdefender has "taken all precautions to make sure that we're not compromising user data" including exhaustive testing and "code that evaluates whether the resulting decrypted file is valid."

Even without Bitdefender, DarkSide might have soon realized its mistake anyway, Wosar and Gillespie said. For example, as they sifted through compromised networks, the hackers might have come across emails in which victims helped by the Hunting Team discussed the flaw.

"They might figure it out that way — that is always a possibility," Wosar said. "But it's especially painful if a vulnerability is being burned through something stupid like this."

The incident led the Hunting Team to coin a term for the premature exposure of a weakness in a ransomware strain. "Internally, we often joke, 'Yeah, they are probably going to pull a Bitdefender,'" Wosar said.

Renee Dudley and Daniel Golden have focused on ransomware for ProPublica and are working on a book about the Ransomware Hunting Team, to be published next year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.