By Doyle McManus, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

It seemed like a good idea at the time. Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR), a rising conservative star, persuaded 46 fellow Republicans to sign a letter to Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei et al warning that Congress could revoke any nuclear deal that President Obama makes.

But as one of Napoleon’s ministers said of a decision that went awry, it was worse than a crime; it was a blunder.

Notwithstanding yelps from overwrought Democrats, the senators’ letter to Khamenei wasn’t against the law, much less treasonous.

Politics hasn’t really stopped at the water’s edge since roughly the Eisenhower administration. Partisanship infected foreign policy long ago.

Still, writing letters to the enemy — and Cotton emphatically views Iran as the enemy — is bad form. When Democrats communicate with U.S. adversaries, Republicans complain too. And writing the enemy with the avowed aim of disrupting sensitive negotiations is even worse.

In the assessment of distinguished political scientist Daniel W. Drezner of Tufts University, “The Iran letter wasn’t illegal. It falls into the more nebulous category of a (dumb) move.” (He used a term we can’t publish in a family newspaper.)

Cotton and his colleagues have every right to object to the kind of nuclear deal Obama is seeking with Iran, of course. But they should send their complaints to the president, not the supreme leader in Tehran.

As a legal matter, what the senators said was true: Technically, Congress has the right to try to undo any agreement a president makes. The senators pretended (a little pompously) that they were educating the ayatollah on this nuance, but Khamenei’s U.S.-educated negotiators surely knew it already.

But it was still a blunder — which some of the 47 senators were slowly realizing last week after they had time to take a second look at what they had done.

“Maybe that wasn’t the best way to do that,” conceded Senator John McCain (R-AZ), although he reaffirmed the letter’s message.

McCain said he signed the letter quickly on a day when senators were rushing to get out of Washington before a snowstorm hit. “I sign lots of letters,” he said.

The letter was a mistake for reasons both foreign and domestic.

It got in the way of a bipartisan effort led by Senator Bob Corker (R-TN) to pass a bill requiring the administration to submit any deal with Iran to Congress. The administration plans to make any deal with Iran by an “executive agreement,” which doesn’t need congressional approval, rather than a treaty, which does. But Congress can still try to block an executive agreement.

With opposition to a nuclear agreement looking like a partisan campaign against Obama, even Democrats who say they’re worried about the deal took a step back from Corker’s proposal.

Indeed, the letter inadvertently strengthened the administration’s argument against submitting an agreement to Congress. If Republicans have made up their minds even before a deal is struck, why bother?

If the letter’s goal was to derail the negotiations, it failed, too — at least in the short run. The wily Khamenei tut-tutted about what he called “the decay of political ethics in the American system,” but said he stood by his negotiators.

“Every time we reach a stage where the end of the negotiations is in sight, the tone of the other side, specifically the Americans, becomes harsher, coarser and tougher,” he complained.

Qom Theological Seminary 1, Harvard Law 0. When an ayatollah sounds more statesmanlike than the U.S. Senate, it’s not a good sign.

Still, as Khamenei’s statement showed, the letter gave the Iranians a reason to stiffen their negotiating posture — and, worse, a useful talking point if the talks fail.

“This is not a trifle,” German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier said last week during a visit to Washington. “All of a sudden, Iran is in a position to turn to us and ask, ‘Are you credible?’ ”

If Iran can convince other countries that the United States is at fault for a breakdown in the talks, it will be harder for any president to maintain economic sanctions that have been the main tool for putting international pressure on Tehran.

That’s a problem for Republican presidential candidates, too, not least because more sanctions is their Plan B for taming Iran’s nuclear program. The GOP contenders already face strong pressure from hawks to renounce the possibility of any nuclear deal with Iran and to promise not to abide by any agreement Obama makes. The moderate position, held by former Florida Governor Jeb. Bush, merely expresses skepticism that a good deal is possible and says a bad deal should be rejected.

And if a deal is reached and one of those Republicans makes it to the White House, what then?

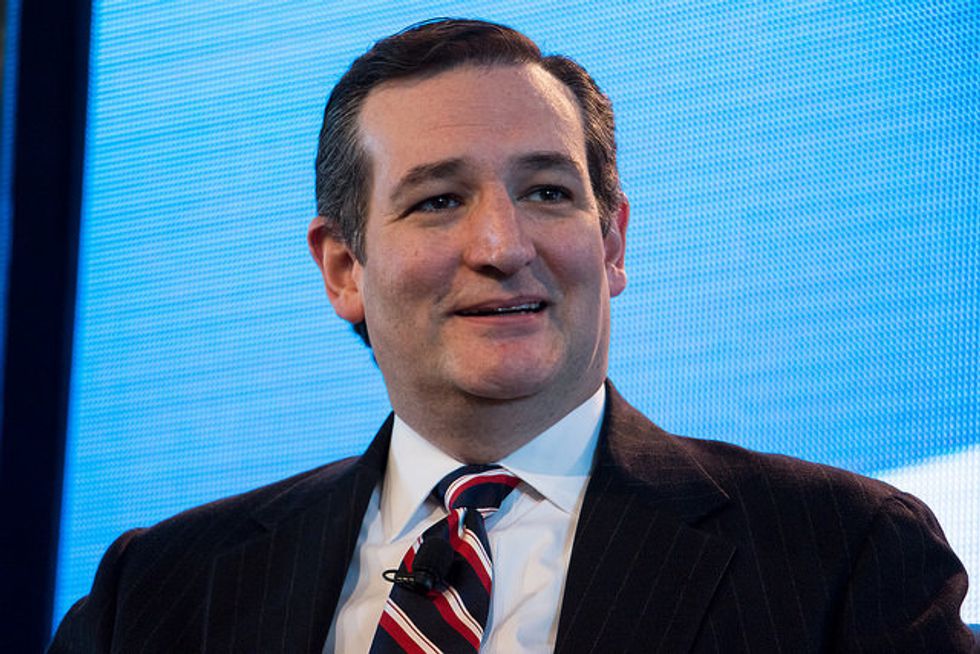

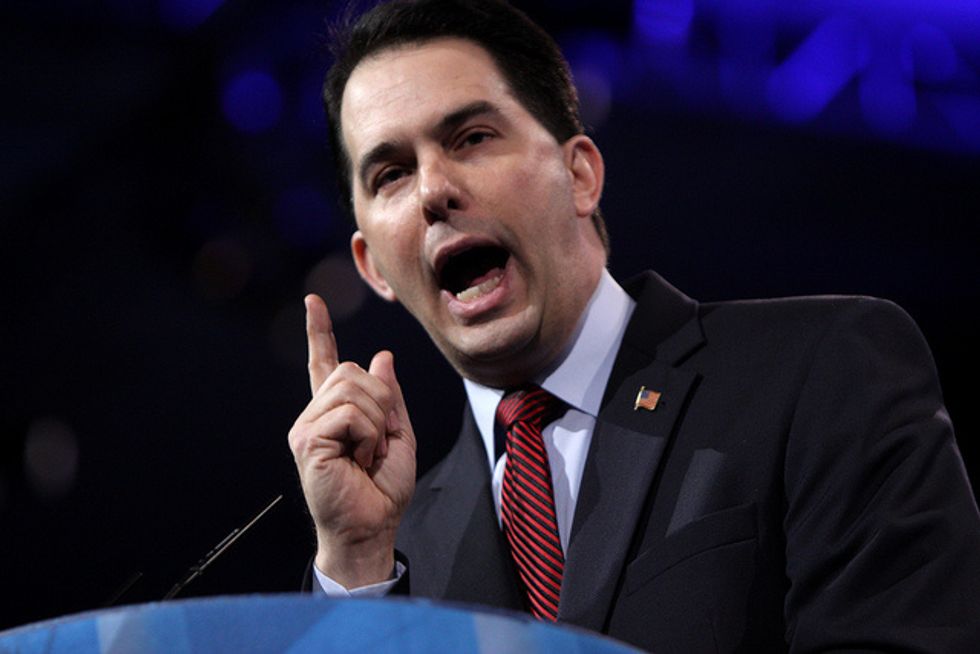

If Iran is complying with an Obama administration deal by January 2017, it’s going to be difficult for the next president — even a President Scott Walker or Ted Cruz — to walk away from that deal.

By then, sanctions will have been relaxed. European allies will have a vested interest in making the agreement work. For the United States to blow the deal up would be a big step; the new president would have to explain why he wanted to alienate the allies and risk war with Iran.

And a new president would face one more constraint: He may not want to confirm the new Cotton Doctrine — the idea that any president’s agreements are good only until the next president shows up. If that were to become the norm instead of the exception, it would only make diplomacy harder for every future president — including Republicans.

Doyle McManus is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times. Readers may send him email at doyle.mcmanus@latimes.com

Photo: Secretary of State John Kerry continued his meetings in Montreux March 4 with Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif. Under Secretary Wendy Sherman and Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz attended the meetings. (US Mission Geneva via Flickr)