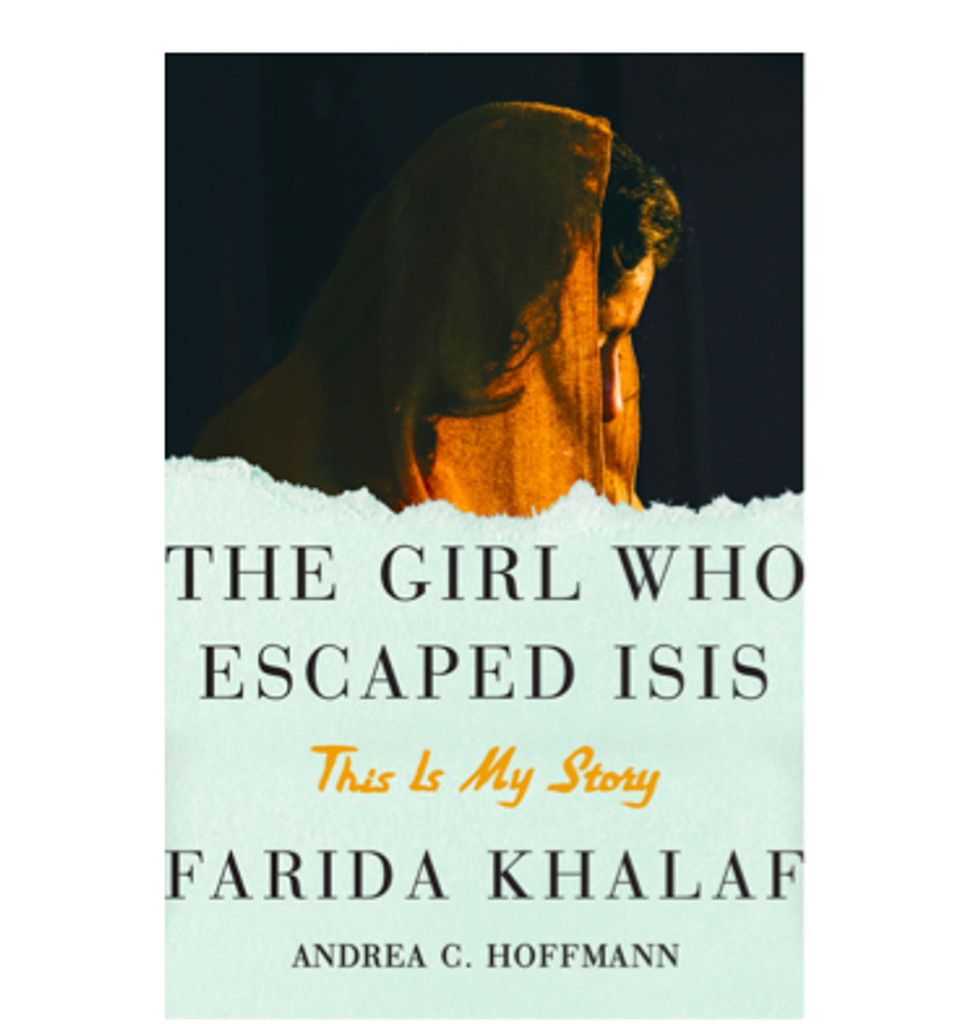

EXCERPT: ‘The Girl Who Escaped ISIS’

It was the summer of 2014 when a young Yazidi woman’s life was flipped upside down. Farida Khalaf was living a normal life in northern Iraq until ISIS took over her village — killing all the men, and enslaving all the women.

In The Girl Who Escaped ISIS, Khalaf describes her existence before tragedy struck. Nineteen and living with her family, she hoped one day to become a math teacher. But that dream dissolved into a living nightmare when she was taken to a slave market in Syria, and then passed around the homes of ISIS soldiers.

But Khalaf was determined to overcome her circumstances, showing resistance throughout her ordeal. Taken to an ISIS training camp, she plans an escape for herself and five other women. Her memoir offers a captivating firsthand account of what life under ISIS looks like, nd the inspiring story of how one young woman’s fighting spirit led her to freedom.

You can purchase the book here.

__

Chapter Three: The Catastrophe

Suicide. I couldn’t get the word out of my head all that evening and night. My father managed to persuade most of our relatives to refrain from taking the dangerous route for the time being. But no one had warned Nura and her family. They had driven straight into the fighting in Sinjar. I was worried to death about my friend. I kept begging Delan to call her father’s phone, as Nura herself didn’t have a cell phone. But he couldn’t get through. “That doesn’t mean anything. ISIS often deactivates the local network when they attack somewhere,” my father said to comfort me. As a soldier he had experience in these things. “Or he’s out of battery.”

My mother too tried to reassure me. She was permanently worried that I would get one of my attacks. I’d suffered from epilepsy since I was a small child. Thanks to medical treatment we’d managed to keep the illness under control. But as soon as my emotional balance was unsettled, I developed problems that could manifest themselves as attacks. “Don’t get worked up, Farida. It’ll be all right. I’m sure she’ll call you in a few days,” my mother said. “Have you taken your medicine?”

“Yes, don’t worry, Mom.”

I went to bed early and fell into a fitful sleep, accompanied by bizarre dreams. I saw the man with the black turban and beard, whom Delan had shown me on the video clip. The “caliph” pointed his finger at my friend. “Nura!” I screamed. Then I heard the rattling sound of machine gun fire. I sat up with a start. Was I awake or still dreaming? The rattling continued.

I also heard my father’s voice, talking animatedly with my mother. The two of them went up to the roof. The night was full of gunfire and shouting. My father was peering through binoculars. “What’s going on?” I asked, still half asleep and yet just as worried as they were.

“Farida, my child.” His voice sounded tender. “They’re attacking Siba.” He passed me the binoculars. “Look, can you see?”

I could make out rocket fire and explosions in the direction where our neighboring village lay. Two of my aunts lived there: Rhada and Huda, my mother’s sisters. Both of them had small children. My mother tried desperately to get through to them on the cell phone. But the network was paralyzed.

“I’ll drive over to Siba,” my father said. “We have to help them.”

But Mom wouldn’t let him go. “It’s too dangerous,” she protested. “Their people must be everywhere. At least wait until the sun’s up. I don’t want to stay here alone with the children.”

He put his arms around my mother to comfort her. And he did wait until dawn. By then the cell phone network was working again, and my aunts called. They had run away from the fighting, fleeing to the hills with the children. “They’ve destroyed everything; we’ve got nothing left,” Huda said in tears. “They’re shooting at everything: men, women, and children.”

“My entire family is dead,” Huda sobbed.

“Where are you now?” Dad asked.

They told him their precise location; it was only a few kilometers from Kocho. “Come to us right away,” he said. But they were too scared that Kocho would be ISIS’s next target. “Then I’ll come. I’ll drive to Siba with a few men.”

“Siba is lost,” they replied. “You should flee now while you still have the chance. Run for your lives!”

After the phone call my father got through to another relative from Siba, who had also fled. But he only confirmed what my aunts had just said. “Whatever you do, don’t come here,” he implored. “It’s full of ISIS soldiers. The battle is lost. Pack up your things and flee to the mountains, or they’ll kill you too.”

My father had heard enough. He informed Uncle Adil and other heads of families in Kocho. All were of the same mind: flight was now the only chance left open to us.

We hectically began packing our things. In the trunk of our Opel Omega we stowed food, warm blankets, a camping stove, two pots, our three Kalashnikovs, and several canisters of drinking water. We also gathered up our valuables: cards, papers, Mom’s jewelry, our cell phones. Then we were ready to go and the seven of us squeezed into the car. All the inhabitants of Kocho had done the same as we and were now sitting in their cars. We’d leave Kocho in a convoy heading north and hope we could make it to the mountains. Somehow. “If you see ISIS soldiers, wave the white flag out of the window,” my father urged us.

Then the convoy got moving. The first cars were already on their way out of the village when the mayor, who was leaving with us, got a phone call. It was from Muhammad Salam, a powerful man in the area. As “Emir,” he was in charge of a number of villages in our region, including the Yazidi villages of Til Banat, Til Ghazeb, Hatemiyah, and Kocho. I’d seen him a few times before on his sporadic visits. He was a tall, gaunt man with a black goatee who always wore traditional Arabic robes. He had a pronounced limp, as his left leg was lame. He frightened me.

“Turn around at once!” Salam ordered our mayor. “You must on no account drive away or you’ll pay with your lives. We’ve come to an agreement with ISIS: if you stay where you are they won’t do you any harm.”

“Are there any guarantees for this?”

“You have my word that you’ll be safe in Kocho,” Salam said. “Now, tell all the villagers to turn back. You won’t get very far anyway; ISIS soldiers have set up checkpoints on all roads. If you leave, your convoy will come under fire.”

The mayor made a sign for the cars to stop. Some had already driven off, including Uncle Adil and Auntie Hadia’s. But most were still in the village. My father and the other men got out and listened to what the mayor had to say. We waited in the car while they discussed the matter with him. Not all the men agreed that you could rely on the Emir’s word; many considered him untrustworthy. One made a call to the Yazidi village of Hatemiyah to find out what the situation was there. The villagers said that Salam had also promised them they’d be safe if they stayed.

“All I can do is relay his words to you,” the mayor said. “Each family must make their own decision.”

From the direction of the main road we could hear gunfire. Clearly the cars that had set off first were being shot at. Some of them turned around to take refuge back in the village. On one, there were bullet holes.

My father returned to us looking gloomy. “Get out. We’re staying here,” he said.

From The Girl Who Escaped Isis by Farida Khalaf and Andrea C. Hoffman. Copyright 2016 by Bastei Lübbe AG, Köln. Translation 2016 by Jamie Bulloch. Excepted by permission of Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter here.