Reprinted with permission from The Washington Spector.

The Alt-Right has been declared the winner. The Alt-Right is more deeply connected to Trumpian populism than the ‘conservative movement,’” Richard Spencer tweeted as the election results rolled in on November 8. “We’re the establishment now.”

The loosely organized, yet newly emboldened, white nationalist coalition Spencer lays claim to as president and director of the National Policy Institute, found itself living out its own dream. Trump, while not exactly one of them, was theirs—and he was heading to the White House.

Its annual gathering held last month—the second I have attended—was to open with a pre-conference shindig at the Hamilton, a popular bar and restaurant in downtown D.C. Yet Spencer’s original plan to indulge in the celebratory haze that surrounded his movement while sipping cocktails in the shadow of the White House was quickly cut short.

The night before the event, Spencer sent out an email informing participants that the Hamilton had “cowardly backed out,” and the event would be held at the Trump International Hotel. There, we were told, a “fashily dressed man” (i.e., a man dressed like a fascist) would direct us to our final destination. Hours before the event kicked off, the Trump International was inexplicably scratched and we were directed to meet at the Friendship Heights Metro station on the border of D.C. and Maryland.

Along with a fellow journalist, Tom McKay of Mic, I hitched up with a small group of NPI participants on their way from the station. Most, if not all, were men—and several were clearly around our age (mid-to-late 20s). As we wandered into Maggiano’s Little Italy, a family-style Italian chain restaurant minutes away from the station, one 20-something proclaimed, “It’s nice to see all these leftists angry and humiliated”—an obvious dig at the protesters who had derailed the initial plan to gather at the Hamilton and, later, the Trump International Hotel.

The “Griffin family reunion,” the benign identity NPI used to secure a space for the hundred or so alt-right sympathizers gathered in Maggiano’s banquet room, turned out to be exactly what you’d expect: predominantly white, male, and young. As we sidled up to the bar, we made note of the online and alt-right celebrities: Charles C. Johnson of doxing and Twitter-ban notoriety; Matt Forney, a writer for the Return of Kings, a “men’s rights” website; Peter Brimelow, founder of VDARE.com; Kevin MacDonald, a noted anti-Semite and editor of a white nationalist publication, The Occidental Observer. Lest we forget, the star of the occasion was Tila Tequila, a D-list celebrity and reality TV-host-gone-white-nationalist (not to mention a flat-earther). And Spencer, of course, who somehow recognized me.

“What’s your name?” he asked after walking across the room to our table.

“Hannah Gais . . .” I replied, hesitatingly.

“Yes, you’ve been to a few of these before,” he noted.

A few of the surrounding attendees glanced over as he verified that I had, in fact, purchased a ticket and had taken the time to register; then he wandered off. I had been “found out.” While I never explicitly denied being a journalist (I was, after all, registered for the press conference), I hadn’t been exactly forthright either.

Tom and I joined a table toward the rear of the room next to that of the guest of honor: Tila. As appetizers made the rounds, we struck up a conversation with our tablemates. One, a graduate student, explained his interest in white nationalism was spurred not only by the men’s rights community but also by one of his professors. He planned on starting his own white nationalist blog focused largely on “uncucking” Christianity. (The more literal definition of “cucking” refers to the experience of a man observing his wife being “taken”—in the Biblical sense—by another, often black, man. The alt-right uses it in various forms to refer to certain states of humiliation or subservience to a liberal agenda.) A middle-aged attendee to my right explained his excitement about what the Trump campaign meant for his views. It’s heartening, he noted, that the election meant you can “no longer be fired for being a Trump supporter.” He bemoaned his earlier inclination to remain silent on topics of interest, like “race realism.”

As the night went on, the atmosphere became increasingly tense. Antifascist protesters had made their way to Maggiano’s, and Spencer—presumably with a few drinks in him—stepped out to confront them.

Meanwhile, Tequila’s speech was canceled, at least for the time being; she busied herself by taking selfies with participants while giving a Nazi salute. A new arrival at our table, a younger blonde man with a shortly cropped haircut, was giving me dirty glances while he whispered to the graduate student bent on “uncucking” the Catholic Church.

The night was being cut short, we were told, and instead of facing off with the protesters, we were to go out the back and then proceed to the Trump International Hotel for drinks. Still, Spencer seemed jubilant—not to mention inexplicably shirtless, after a confrontation with protesters. We may have gone out of our way, he explained to the enthusiastic audience, but it was worth it to meet up. And “we have a culture; we have a right to do this. Go to Hell!”

“I was about to say something sarcastic like, ‘Party like it’s 1933’” he said, as loud cheers erupted from the audience. “That joke is outmoded. We’re going to party like it’s 2016!”

As attendees began to gather their things, the man who had been sitting to my right approached to ask if we were journalists. As he berated us, he grabbed my phone out of my breast pocket, asking repeatedly if I’m recording video or audio. I yanked it back as he continued his lecture on the “ethics” of journalism. We needed to be honest about who we are, he said. Tom responded that we’re writers interested in the alt-right. And, for the record, no one even asked me what I did.

We walked out, past several police officers and a small gaggle of journalists crowding the stairs. Spencer followed shortly thereafter to chastise the protesters.

“Are you the same person? The same formless, genderless blob?” he asked me outside. “I’m onto you, and this is the last time you pull this.”

* * *

On Saturday, I made my way to the Ronald Reagan International Trade Building, a frequent venue for NPI conferences and also home to a number of governmental and nongovernmental organizations, including the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Woodrow Wilson Center, U.S. Customs and Border Control, and the Environmental Protection Agency. I cabbed to the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 14th Street. The District’s newest museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, was visible down the street. Vendors were hawking Obama trinkets and T-shirts proclaiming “Black Lives Matter.”

At the start of the conference—dubbed Become Who We Are, a riff on Friedrich Nietzsche’s imperative to “become what one is”—Spencer declared that all members of the press would be subjected to a slew of legalese dictating how we were to behave. So I identified myself as press. The NPI volunteer responsible for checking in guests shrugged and explained that, because I had paid for my ticket, all was well. He handed me a name badge.

The ballroom wasn’t filled to capacity, but it was crowded. Nearly 300 people gathered around banquet tables with cups of coffee, eyes glued to Spencer as he offered an introduction and a tribute to a movement he’s nurtured for years: the alt-right.

Plenty of ink has been spilled over the origins of the term “alt-right”—a loosely affiliated white nationalist and explicitly racist movement that’s fed off Donald Trump’s momentum. Yet the goals and interests of the group meeting in the Reagan Building are hard to define. While the term “alternative right” was first used by Paul Gottfried in a 2008 speech to the H.L. Mencken Club—where he called for an “independent intellectual Right,” an inheritor, of sorts, to the paleoconservatives—it’s commonly attributed to Spencer. After a short-lived stint at The American Conservative and Taki’s Magazine, a paleoconservative outlet founded by TAC co-founder Taki Theodoracopulos, Spencer took his energies elsewhere. The Alternative Right, a webzine he founded in 2010, could be seen as the movement’s more formal unveiling. With Gottfried as a progenitor of the movement, it was only appropriate he signed on as a contributing editor.

Spencer took the reins at the NPI about a year later, following the death of its long-time chairman, Louis R. Andrews. Under Spencer’s leadership, the institute founded its flagship publication, Radix Journal and shifted its headquarters to Spencer’s place of residence in Whitefish, Montana—a upscale resort town in a state that’s rapidly becoming a hotbed for white nationalists. The institute briefly made headlines when Hungarian officials shut down a conference organized by NPI, Jared Taylor of the white nationalist publication American Renaissance, and others in Budapest. Spencer was detained, and NPI founder William Regnery II was promptly returned to the United States after his arrival in Hungary.

Spencer and others had been making inroads with far-right extremists in both the United States and Europe for several years, but the “alt-right” as we know it now owes much of its strength to the 2016 presidential campaign. Where liberals and leftists turned away in disgust from Trump’s brash, overt racism and Islamophobia, Spencer and others saw an opportunity.

The resounding explanation of Trump’s appeal to the white nationalist crowd is that he advanced issues important to them, albeit in language that made them acceptable to “generic Americans”—a term used by Brimelow to describe a national coalition of heterosexual, non-Jewish whites. Taylor, the white supremacist, echoed these sentiments, observing that “it’s impossible to know why people voted for Donald Trump.” At the rallies he attended, he observed that few Trumpites addressed the issues the alt-right considers important. Establishing a white ethnostate, it turns out, isn’t a popularly held position, even among a crowd that’s gleefully supporting an anti-immigration candidate.

“We willed Donald Trump into office, we made this dream our reality!” Spencer said later. It was as if the movement had “crossed the Rubicon in terms of recognition.”

There’s some unnerving truth to this. Since I wrote about the NPI and its allies in the broader far-right movement in the winter and spring months of 2016, individuals and groups linked to the alt-right have received extensive coverage in places such as The New York Times, Time, Bloomberg News, Mother Jones, Wired, Highline at Huffington Post, NPR, and even at the BBC. Although many on the alt-right, including Spencer, prefer to refer to the media as Lügenpresse—or “lying press”—and deride journalists as stupid, the media have been instrumental in legitimizing the movement. (Spencer even said as much in his appeal to journalists during the press conference that day to protect the alt-right’s free speech rights.) As Ryan Lenz of the Southern Poverty Law Center explained to me, the press has allowed Spencer and others to hide behind the “comfortably innocuous label the alt-right” without sufficiently explaining that these groups are white supremacist in nature. Some, like the Associated Press, have made an effort to enact clearer guidelines on how to use the term without whitewashing what the movement stands for. And while Spencer and others insist the term isn’t an attempt to mask their beliefs, the movement’s title implies its adherents ought to have a place in mainstream American political discourse.

Despite all the media coverage, defining what some adherents prefer to be called the “alt-right” has proven to be tricky. It’s not that Spencer and his crew have succeeded in developing a “big tent” approach to political organizing—there’s plenty of infighting to go around. But as a catch-all term for a movement bent on countering what it sees as “establishment” conservatism, using the term as if its definition is self-evident sort of misses the point.

There were hints of this muddled identity at the conference. VDARE.com’s Peter Brimelow said in his speech that he couldn’t define himself as “alt-right” for two reasons. For one, he noted, “I’m too damn old,” he said to a room where most were under 40. “The second reason I can’t claim to be a member of the alt-right is haircuts,” he explained, his mane of curly white hair as evidence.

Though Brimelow’s comment was tongue-in-cheek, it points to deeper divisions preventing an understanding of the movement as a whole: who, beyond a loose-knit band of white nationalists that gathers each year in the Reagan Building and at events such as the American Renaissance conference, is the “alt-right”? Are they the shitposters and keyboard warriors splattering Pepes on 4chan, 8chan, Reddit, and the newly launched “free speech” network Gab? Are they the self-styled intellectuals who gathered in the Reagan Building in mid-November to bask in Trump’s win? Or, as many in the media have argued, are they Steve Bannon and his army of scribblers at Breitbart?

While Bannon has attempted to disavow the “racial and anti-Semitic overtones” of the alt-right, he’s seized upon his own definition—largely for the sake of boosting Breitbart’s popularity—of the group as a home for “younger people who are anti-globalists, very nationalist, terribly anti-establishment.” Yet the alt-right’s more contrarian writers insist there’s one crucial modifier missing from Bannon’s pro-nationalist push: “white.” Indeed, as Greg Johnson argued in the new-right Counter Currents site after Hillary Clinton’s speech in August condemning the alt-right, “the Alternative Right means White Nationalism—or it means nothing at all.”

Spencer and his clan show no intention of letting that connection die. Hours after most reporters left the Saturday session, a camera crew recording the conference for an upcoming documentary caught him closing the night with a grandiose Hitlerian tribute to Trump. “Hail Trump! Hail our people! Hail victory!” he shouted before the jubilant crowd. Several hands went up in enthusiastic Nazi salutes.

The speech, dripping with contempt, was a set piece from another era. “To be white is to be a striver, a crusader, an explorer, and a conqueror,” Spencer said, echoing a sentiment that bleeds through the pages of Mein Kampf. “We build, we produce, we go upward, and we recognize the central lie in American race relations. We don’t exploit other groups. We don’t gain anything from their presence.”

“They need us and not the other way around.”

* * *

Spencer and his followers couldn’t hold an event in Washington without attracting protesters eager to confront him.

Members of the DC Anti-Fascist Coalition followed NPI through all its last-minute schedule changes and on to the restaurant at Friendship Heights. Protesters pushed into the dining area and up the stairs to confront participants, all the while chanting “No Nazis, No KKK, No Fascist USA!” Spencer left the party to confront them. By the time he returned, he had stripped off his shirt and was wearing nothing but pants, shoes, and a vest—he soon claimed that the protesters had attacked restaurant employees with mace.

Spencer’s account was little more than a fabrication, several protesters informed me. There was no mace at the protest, although something smelling much like farts was sprayed on Spencer and his followers. “It seems like sometimes the culture war is actually a war,” he tells the crowd. “And that’s what we’re up against.”

By Saturday, the number of protesters had swelled—as had the press coverage.

The crowd was diverse, with members of various unions, immigrant-rights and church groups, and members of the Democratic Socialists in attendance. Andrew Batcher, a member of the DC Anti-Fascist Coalition, estimates that almost 500 protesters came through on Saturday.

With one or two exceptions, few conference attendees approached or engaged the protesters. Emily—a member of Red Ice Radio, a white nationalist outlet that had been providing live video coverage of the event—wandered into the group with her cameraman to “interview” protest participants. “Are you a self-hating white person?” she asks one group, thrusting a microphone in their faces. The situation escalated quickly, and her cameraman was pushed to the ground. He rose with a cut on his forehead. The media swarmed.

Overall, though, Batcher told me in an email about a week later, the direct action he helped coordinate was successful. “We got the Hamilton to cancel [NPI’s] reservation. Maggiano’s donated their earnings. And we got a lot of media coverage which linked the alt-right to [the] KKK and neo-Nazi style white supremacy. We also got a lot of people involved, both marching in the streets . . . and through call-in campaigns. We met most of our goals, and realize this is something to build on.”

That raises the question, though: Did NPI’s leaders meet theirs?

* * *

Although the number of hate groups grew by 14 percent in 2015, there may be some hope for those concerned about the alt-right’s rise.

Indulgent fantasies of a white ethnostate and pseudo-intellectual beliefs about the nature of race and ethnicity may be what keeps Spencer, Taylor, MacDonald, and others going, but at the root of it, their followers are driven by fear and anger.

But over what? Outsourcing? For those of us in our 20s, many of whom found their voices among these extremists, that process was underway by the time we were legally able to work. For many of us, it was really the 2007–2008 crash that took a toll on our own budding careers—and that had more to do with pure corporate greed and an unmitigated desire to treat the middle class as pawns in get-rich-quick schemes.

But this is not about economic dislocation or anxiety. What the alt-right is mourning is a community that never existed. While the United States has been home to a certain class of elites with ancestral roots in Europe, the barriers to entry have been constantly in flux. Protecting and enforcing white supremacy may undergird much of our history and law, but that definition of “whiteness” has always been fluid. Spencer’s praise of Russian and Eastern European nationalists would be considered heretical among his movement’s ancestors in the 1920s and 1930s, when immigration quotas targeting Italians, Slavs, and Greeks were all the rage. And while the alt-right’s demand to shut down immigration in the next 50 years may seem in line with, say, South Carolina Senator Ellison DuRant Smith’s impassioned defense of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, and of shutting the door until we can “breed up a pure, unadulterated American citizenship,” to borrow DuRant’s words, it’s unlikely that Spencer and Smith could have agreed on the fundamental terms that defined their movements.

What does it mean to be “European”? Being of European ancestry doesn’t capture the totality of these new white nationalists’ definition. For those of us of European heritage, the wave of imperial decline and the ever-changing borders of European nation-states in the late 19th to 20th century make discerning our place on the continent difficult, if not impossible. Instead of grappling with these nitty-gritty details, this new generation of white nationalists resorts to nonsensical, ahistorical universalisms. They take pride in unearthing “the European mind,” on articulating a “white identity” rootedin these nebulous geopolitical configurations. But whose Europe? Whose “white identity”?

The community of European whites imagined by Spencer is and always will be imagined. Its issue is not that it is a transnational or supranational community; the white nationalist formulation claims to have identified race as something more primordial. Yet, this racial “nation” never has, and never will, exist. It cannot even be imagined; the base elements of it are too flimsy for a community to even be “manufactured.”

In the end, the alt-right’s downfall will be itself. In the days following NPI’s conference, some of those affiliated with the movement began to turn on Spencer. Paul (RamZPaul) Ramsey, a featured speaker at the first NPI event I attended in March, stated his intention to distance himself from the alt-right over the “Sieg Heil” controversy that arose from the events on Friday and Saturday in D.C. In a podcast reposted on Spencer’s former webzine Alternative Right, Andy Nowicki exclaimed: “The alternative right is not its putative Führer Richard Spencer. And Richard Spencer is not the alternative right.”

It’s too soon to tell what will become of the alt-right. Soon, Spencer will begin his post-“Heil-gate” victory lap—a term he used in a recent podcast to refer to the outrage following the overt neo-Nazi references and behaviors at the conference—with a speech at Texas A&M. The alt-right is ready to capitalize on Trump’s win. The question, though, is whether it will destroy itself in the process.

Hannah Gais is associate digital editor at The Washington Spectator.

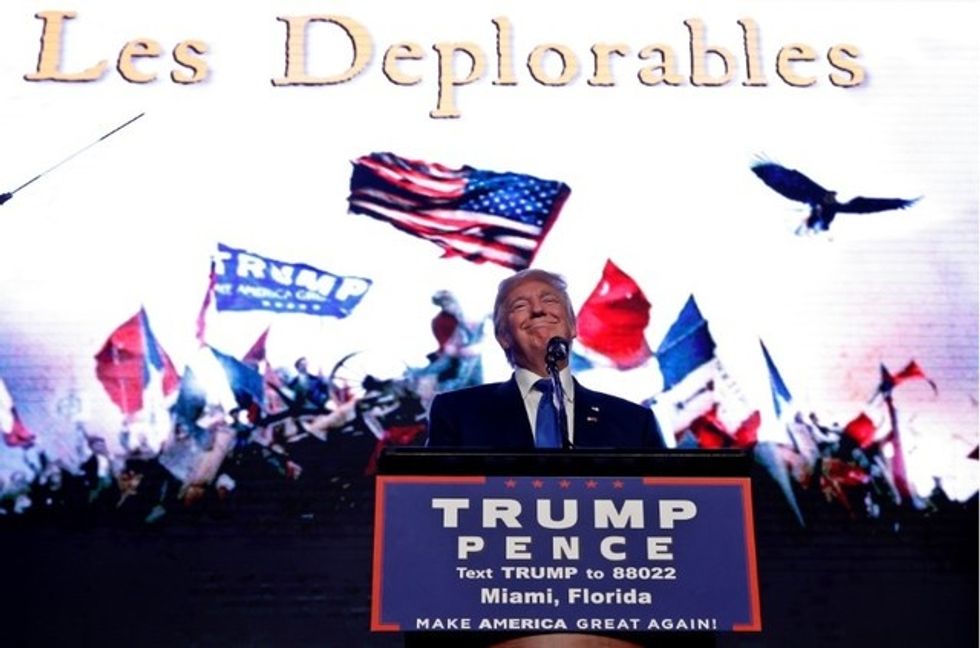

IMAGE: Donald Trump appears at a campaign rally in Miami, Florida. REUTERS/Mike Segar