Has Trumpism Made The World Less Safe For Jews?

Reprinted with permission from AlterNet.

Earlier this month, a lifetime ago in the Trump administration, an art dealer named Todd Brassner burned to death in a fire at Trump Tower. (The building did not have a sprinkler system on its residential floors because its eponymous owner refused to install one, citing its prohibitive cost). According to the New York Daily News, real estate mogul Trump was less than enamored of Brassner, reportedly referring to his tenant as “that crazy Jew.” The scandal barely registered with the American public, but it offered yet another reminder that the Oval Office is still oozing with anti-Semitism, even after the departures of white nationalists like Steve Bannon and Sebastian Gorka.

Bigots and bullies have grown emboldened. The Anti-Defamation League tallied1,986 anti-Semitic attacks in 2017, up 57 percent over the year prior. Schools proved the most common place for these incidents; 457 were perpetrated against children grades K-12. American Jews have not faced the kind of overt persecution that Muslims, African Americans and Latinos have since Trump assumed office, but as Jonathan Weisman warns in his new book, now is no time for diffidence or retreat.

One part memoir, two parts sociological study, (((Semitism))) explores what it means to be Jewish in Trump’s America, with all of its inherent possibilities and dangers. (The triple parentheses allude to the so-called alt-right’s method of marking Jews on social media for online harassment). Days ahead of a neo-Nazi rally in Newnan, Ga., AlterNet spoke with Weisman over the phone about the rising tide of white nationalism, American Jewish organizations’ singular obsession with Israel and the need for Jews across the country to form broad coalitions. The following conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

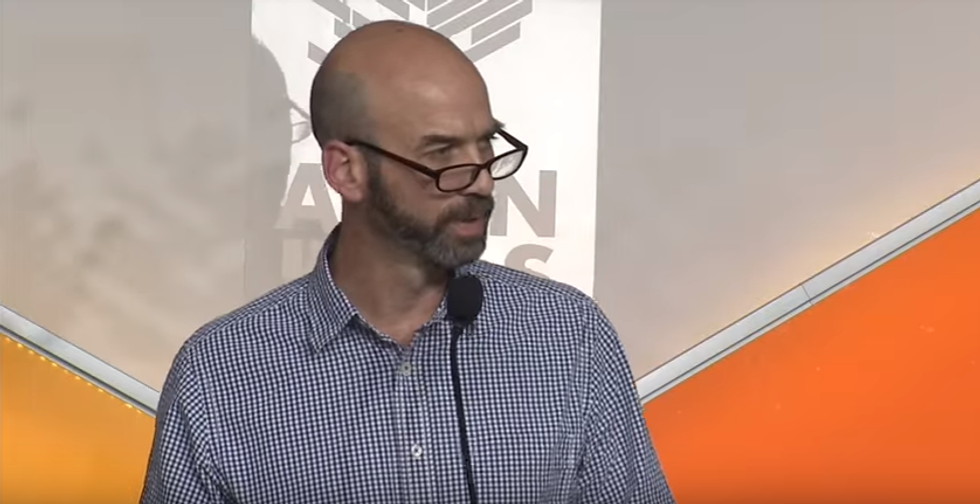

Jacob Sugarman: You yourself acknowledge that there are other religious and ethnic groups who are even more imperiled by Trump’s presidency than American Jews. Why do you think it’s important to explore the wave of anti-Semitism his run for office and subsequent election appear to have triggered?

Jonathan Weisman: When white nationalists talk about so-called white genocide, they imagine that white human beings, specifically white men, are being supplanted and driven out by brown people: African-Americans, Latinos, Muslims and immigrants more generally. But their mythology also tells them that these brown people are inferior beings, so they summon the Jews as the cause of their demise, the answer to the question, “How could this be happening to us?” It’s the Jews, they believe, who are the puppet masters, pulling the strings of the ethnic hordes. You can’t separate one group from another, we’re all in this together.

The American Jewish community also has a certain amount of power and resources to bear in this fight. If a Jew stands up and screams, “Anti-Semitism,” the response is often, “You’re just being parochial. There are other people who have it far worse than you. What are you doing?” That’s why it’s so essential we form alliances with Muslim Americans, immigrants, Latinos and African Americans to denounce all forms of bigotry.

JS: Does Trump pose a unique threat to Jews, or is he simply channeling hatreds that have always been present in American society?

JW: I’m not sure I’d call it a unique threat because the globe goes through spasms of nationalism, and these spasms tend to be bad for Jews. The rise of white nationalism is international, and Trump is proof that it has arrived at the shores of the United States. If you look at [Viktor] Orban’s Hungary, or what’s happening in Poland, or the last elections in Italy, or Golden Dawn in Greece, you have to think that the virus is spreading. Things are demonstrably worse in Europe than they are in the U.S., but we’re at a dangerous moment in history.

JS: I’m glad you brought up Hungary and Poland. Has Trump’s victory rekindled anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe?

JW: Absolutely. There’s no question that the white nationalists in Europe look at the president as a kindred spirit. They feel they have some momentum, and with Trump in the Oval Office, they no longer have to fear the United States as a bulwark against their movement.

JS: If we can wind back the clock two years, why do you think American Jewish organizations were so tepid in their response to Trump’s presidential campaign? Did they fail to recognize the threat he posed?

JW: Over the last 20 years, whether they’re liberal outfits like J Street and New Israel Fund or conservative groups like the Republican Jewish Coalition and AIPAC, mainstream Jewish organizations have become obsessed with Israel. To an extent it’s understandable, because at least for now, support for Israel may be the one thing that Democrats and Republicans can agree on. You’re not going to get into trouble with potential donors or supporters by focusing on the Israeli cause. But this focus has come almost at the exclusion of domestic politics in the United States. Few realize that the white nationalist movement actually emerged in the later Bush years, after the public had soured on the Iraq War and later with the collapse of the financial system. Conservatives were looking for a new rallying cry. Most people, virtually everybody, ignored the alt-right for eight years. And during that time, American Jews were basically arguing about Israel.

JS: How did the concern of these organizations become so blinkered, and do you believe it has affected their commitment to social justice?

JW: Money is obviously a big part of it, but it’s also complacency. The United States from 1960 to 2016 felt like it was on slow but steady trajectory toward a more pluralistic, inclusive and tolerant society. I think these organizations were completely blindsided by this latest surge of nationalism. They had been looking for a cause to rally behind, and Israel offered an obvious one.

JS: At the risk of falling into the same trap, do American Jews have a responsibility to speak out against the recent violence on the Gaza border?

JW: You have to understand that Jews in their late teens and early 20s have grown up experiencing nothing but Likud politics, with no exposure to hope in the Middle East. They don’t know an Israel with a Labor or a centrist government. They don’t remember the Oslo Accord, and they certainly don’t remember the Camp David Accord. On their left, they have the BDS movement, and on their right they have their elders telling them, “Part of your Judaism is bound to your fealty to Israel.”

I believe very strongly that if love of Israel is a prerequisite to Jewish identity in this country, then we’re going to lose an entire generation. It’s probably the biggest threat facing the American Jewish community today—that drift of young Jews away from Judaism because of the demands that Israel puts on them. Jews should be able to embrace their religion and their identity without having to answer to the latest atrocity in Gaza.

JS: Why do you think anti-Semitism and militant Zionism have proven so compatible? At least superficially, Likudniks and an administration that has featured the likes of Steve Bannon and Sebastian Gorka would appear to make for strange bedfellows.

JW: I think the more you study alt-right ideology, the less strange it appears. Unlike the kind of anti-Semitism that you see emerging in the British Labour Party or on the French left, the alt-right is not especially anti-Zionist. They view Israel as a model ethno-state for their own country. There’s no incompatibility with white nationalism because they believe Jews have a place to go and should go there.

JS: I have to push back a little bit here. Are you really suggesting that Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party is rife with anti-Semitism?

JW: I wouldn’t go so far as to call him an anti-Semite himself, but absolutely, I think anti-Semitism is a real problem in the Labour Party and that Corbyn has been especially reluctant to confront it.

JS: How did Gamergate presage the 2016 election, and why does misogyny so often serve as a gateway drug for overt racism and anti-Semitism?

JW: For most of the decade, members of the alt-right talked to themselves in their own little online ghettos at the National Policy Institute and Taki’s Magazine, and then at the Daily Stormer, Stormfront and other neo-Nazi publications. Gamergate showed that they could spread their ideology in the chat rooms of 4chan and 8chan, the comment sections of YouTube and eventually on Twitter—that through doxxing, trolling and other tactics, the web could be weaponized. And remember, there was a bridge from one movement to the other. One of the great orchestrators of Gamergate was Milo Yiannopolous, who parlayed his notoriety into an editing gig at Breitbart and later emerged as a celebrity on the alt-right.

I talked to

Zoë Quinn, and she believes that Gamergate was like a signal flare to white nationalists. They said to themselves, “Oh my God, we can do that too.” And it took very little time for the harrassment campaign to turn anti-Semitic, because Quinn’s boyfriend was a Yeshiva-educated Jew. Before long, trolls were threatening her with rape and posting photo-shopped images of her covered in semen.

The entire episode was a trial run for Trump’s presidential bid. All of the abuse heaped on Quinn, Brianna Wu and other women video game designers was redirected not just at political journalists on the campaign trail, but the Jews of Whitefish, Montana. (The National Policy Institute is based in Whitefish, as is the mother of alt-right founder, Richard Spencer). As for why misogyny leads to anti-Semitism, I think feelings of sexual frustration or humiliation can be a powerful source of hatred. And hate breeds hate, right?

JS: Donald Trump won’t be president forever, even if he wishes he could be, so what hope do we have of mending the hole his political ascent has torn in the social fabric? You advocate for American Jews to assume their place in the public square, but given how insular our media consumption has become, are we sure one still exists?

JW: You know, I actually think it does. I’ve been doing a lot of traveling to promote the book, and everywhere I go, I’m asked, “What can we do?” I’m a journalist; I’m not a social activist or a community organizer, so my answers are limited. But I think that there’s a desire out there to build alliances, and you’re seeing it now. I recently spoke to a Jewish organization on Long Island, and its first instinct after a swastika was found scrawled on a local synagogue was to form an interfaith coalition against bigotry. People understand we cannot be a series of atomized organizations standing up for ourselves. I believe we’ll remember the age of Trump as a re-emergence of activism on a very local level.

Jacob Sugarman is a managing editor at AlterNet.