A Case Study: How GOP And Trump Deregulators Are Killing Workers

Reprinted with permission from DCReport.

Reuters reporters Julia Harte and Peter Eisler have assembled a powerful investigative article on how “the Trump administration’s plan to weaken the beryllium rule offers a case study in the renewed power businesses can wield in the regulatory process.”

OSHA’s standard to protect workers from the disabling and deadly effects of beryllium exposure was issued in the waning days of the Obama administration. Exposure to beryllium dust causes chronic beryllium disease and lung cancer. Symptoms include difficulty breathing/shortness of breath, weakness, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, joint pain, cough and fever. Over time it may lead to disability and death.

OSHA had been working on a new standard to update its seriously outdated beryllium standard for 20 years, and it was an agreement between the main beryllium producer Materion and the United Steelworkers that enabled OSHA to push the new standard over the line before Trump took office. The labor-industry agreement reduced the Permissible Exposure Limit, added “ancillary provisions” requiring exposure monitoring, training, medical surveillance and other provisions, and covered general industry (e.g. manufacturing) worker. OSHA also added protections for construction and maritime workers who are mainly exposed during the process of abrasive blasting using ground coal slag to remove rust and paint from ships and other structures.

The Trump administration’s plan to weaken the beryllium rule offers a case study in the renewed power businesses can wield in the regulatory process.

Exposure to beryllium dust has devastating health effects on exposed workers like Wardell Davis who was an abrasive blaster with a Norfolk, Va., shipbuilding contractor:

Then 24 years old, with no high school diploma, Davis had for years bounced between part-time jobs. The contractor, he says, promised better pay for the grueling labor of blasting the hulls of U.S. Navy ships with coarsely ground coal particles to remove rust and paint. He recalls the fog of dust created as workers fired the crushed coal – a residue from coal-fired power plants – against the ship bottoms from high-powered hoses, moving through the tented blasting area in respirators and protective suits.

A year later, Davis found a better job with a plumbing and heating company. He became a father, but still found time to hit the YMCA most days for a swim, a lifelong passion. Then, in 2011, he began struggling to hold his breath underwater; soon, he couldn’t hold it at all. He was dogged by a persistent cough, sweats and nausea.

In 2014, doctors at Norfolk’s Sentara Hospital found a “black foreign material” in his lungs. Davis successfully filed a disability claim for “pneumoconiosis/silicosis and/or interstitial fibrotic disease caused by exposure to abrasive blasting dust.” Four years and three biopsies later, Davis survives on a single lung.

Unable to work, he lives on disability payments, and has brought suit against abrasives manufacturers and safety equipment providers he alleges failed to protect him. They deny responsibility for his failing health.

“If I ever would have thought that this would have happened to me, I would’ve never ever worked there,” he told Reuters, his words punctuated by coughs. “Ever.”

The Reuters article describes the fierce industry opposition to the part of the standard that covered construction and maritime industries, not because the regulated industries themselves had strong objections (they could use safer alternatives to coal slag), but because the sellers of coal slag feared devastating effects on their sales as shipyards and construction sites moved to safer alternatives for abrasive blasting.

In June 2017, OSHA issued a proposal rolling back protections for construction and maritime workers. As I wrote then:

Today’s proposal keeps the new PEL, but removes the “ancillary provisions” for construction and shipyard workers. The ancillary provisions would have required employers to provide exposure monitoring, regulated areas (and a “competent person” in construction), a written exposure control plan, personal protective equipment (PPE), and work clothing, hygiene areas and practices, housekeeping, medical surveillance, medical removal, and worker training for construction and shipyard workers exposed to beryllium from abrasive blasting using coal slag compounds that contain beryllium.

Without the benefits of the air testing and health monitoring requirements, the exposure limits for beryllium – are meaningless.

As the Reuters article explained, the new proposal ignored the benefits of the rule and significantly weakened protections:

The protections would cost affected industries nearly $12 million a year, or about $1,000 per worker, according to the 2016 cost-benefit assessment. That analysis, a mandated component of the rule-making process, put the savings to society from averted deaths and illnesses at nearly $28 million, yielding a net economic benefit of about $16 million a year.

Without the benefits of the air testing and health monitoring requirements, the exposure limits for beryllium “are meaningless,” said David Michaels, who headed OSHA for seven years under Obama.

“If there’s no air testing or disease surveillance, there’s no way to know how much exposure workers are getting or who may be getting sick,” said Michaels, who now teaches at the George Washington University School of Public Health.

The changes were unprecedented in OSHA’s almost 50-year history. According to Deborah Berkowitz, OSHA’s former chief of staff, now working for the National Employment Law Project, a nonprofit workers rights group, “Never in OSHA’s history has the agency decided to roll back worker protections for a carcinogen.”

And as I explained in the article, OSHA’s “argument ran against decades of OSHA protocol, which held that if significant risk of exposure to a hazardous substance cannot be completely eliminated, “ancillary provisions” are necessary beyond existing protective equipment, said Jordan Barab, former deputy assistant secretary of OSHA under Obama.”

All of the above is fact. But why did OSHA decide to upend these protections? And here we get to the ability of powerful business concerns to reduce badly needed worker protections.

Leading the charge to weaken worker protections was Congressman Bradley Byrne (R-Ala.), chair of the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections until Democrats took over the House of Representatives this month. Byrne had met with two abrasive manufacturers Mobile Abrasives Inc and Harsco Minerals, who were members of an industry group, the Abrasive Blasting Manufacturers Alliance (ABMA). Byrne wrote to the White House Office of Management and Budget, asking them to weaken the worker protections. Much of Byrne’s letter was taken word-for-word from comments submitted by the ABMA’s lobbying firm, Squire Patton Boggs.

The plot thickens further:

A former Former Patton Boggs senior partner Mark Cowan, a lobbyist who served on Trump’s Labor Department transition team, also became involved. On March 7, Cowan, who served as deputy head of OSHA under former President Ronald Reagan, attended a meeting at the Labor Department, where Squire Patton Boggs lobbyists asked agency lawyers about OSHA’s plans for the beryllium rule. Cowan later wrote an essay arguing that, thanks to existing safety rules, the workers “were never threatened by beryllium exposure to begin with.”

On May 15, Harsco employees and Cowan attended another meeting at the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. Seventeen days later, OSHA announced a second delay in the rule’s implementation. And on June 27, OSHA announced its proposal to revoke the safety requirements entirely.

Both Byrne and Robert Wittman (R-Va.), then-chairman of a House subcommittee overseeing Naval programs and infrastructure had received significant campaign contributions from the Shipbuilders Council of America and the Associated Builders & Contractors.

The abrasive blasters and the other industry associations argue that existing protections are sufficient, and no abrasive blaster has ever been diagnosed with beryllium-related disease.

But not so fast, say Harte and Eisler. It turns out that:

No one is officially checking for such illnesses, say dozens of occupational health specialists and worker safety advocates interviewed by Reuters. The symptoms of berylliosis – shortness of breath, a persistent cough, fatigue – are similar to those of some other diseases. As a result, diagnosing the malady requires a specific blood test that just a few laboratories in the country perform, said one of the labs, the National Jewish Health Advanced Diagnostics Laboratories. They cost about $300 per person, the lab says.

The nonprofit Center for Construction Research and Training, a research arm of North America’s Building Trade Unions that has partnered with OSHA to educate construction workers about health hazards, has researched beryllium exposure. In a series of studies, it found airborne beryllium concentrations of more than 40 times the new permissible exposure limit during coal slag abrasive blasting operations. Other studies by groups including the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found beryllium-related health problems in various construction trades.

Lee Newman, a beryllium researcher at the University of Colorado, Denver, said he has treated construction trades workers who did demolition work and went on to develop berylliosis. Berylliosis “definitely” afflicts such workers, he said.

“To say otherwise is to ignore the published science on the subject,” Newman said.

So the Trump administration’s war on workers proceeds as they continue to ignore the fact that – in the words of former OSHA head David Michaels—regulations don’t kill jobs; they keep jobs from killing workers.

OSHA has suspended enforcement of ancillary protections for shipyard and construction workers, but the agency has not yet issued its final revised beryllium standard. In order to weaken worker protections, agencies have to summon strong and convincing evidence that the reasoning for the current protections were either wrong, that conditions have changed. Worker advocates believe that OSHA’s arguments in the proposal were weak, but weak evidence hasn’t stopped Trump administration agencies from weakening protections for workers, the environment or consumers before. Following issuance of the weakened standard, labor unions and other worker advocates will undoubtedly sue the administration.

Meanwhile, the time has passed when the Trump administration can get away with ignoring their mandate without answering for their deeds.

U.S. Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Va.), the new chairman of the House Committee on Education and Labor, said in response to Reuters’ questions that the panel will investigate whether OSHA has “valid economic or scientific rationale” to eliminate the beryllium rule’s shipyard and construction provisions. The Virginia Democrat noted that OSHA has routinely included such provisions in other health standards, including a rule on toxic silica dust. By killing those provisions for beryllium, he said, “the Trump administration has created a double standard.”

And as we wrote last week, the White House has approved OSHA’s rollback of the Obama administration’s recordkeeping standard. Because of the government shutdown, we don’t know yet exactly what it says, but with a new Congress, it’s unlikely that OSHA will get away with that without defending itself before Congress.

The battle to protect workers is far from over. In fact, it’s just heating up. Stay tuned.

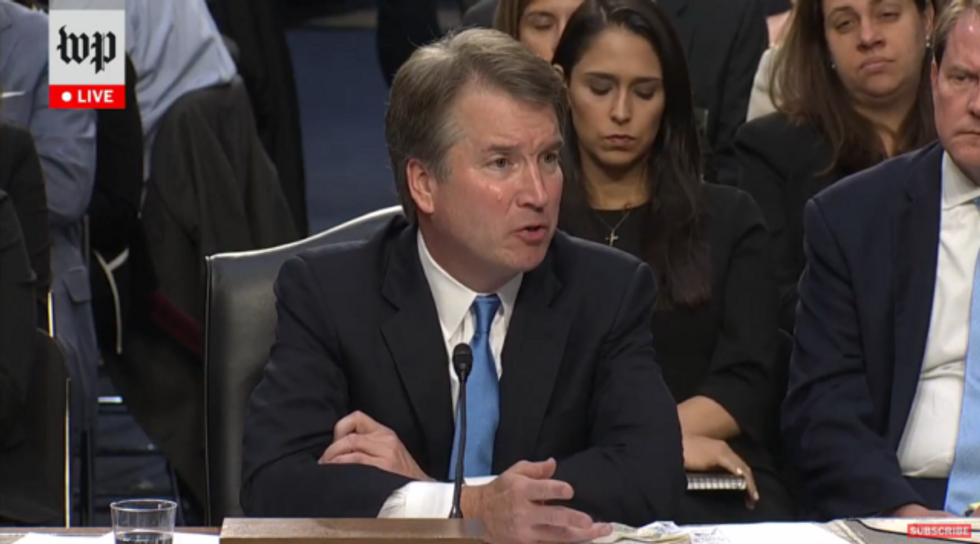

Featured image: Wardell Davis suffers from a debilitating lung condition. Photo by Reuters/Julia Rendleman